Lynn Conway, the technology pioneer and transgender trailblazer who helped revive the microchip industry, has died aged 86.

As a talented computer architect in California’s Silicon Valley in the 1960s and 70s, Conway co-invented a new method of designing microchips that now power nearly every digital device in our lives, from smartphones to in-car electronics.

But, during those years, she was secretly transitioning gender with great personal and professional costs, at a time when violence was regularly directed at transgender people and they were often denied the protection of the law.

After retiring, she came out publicly and began sharing her story on her personal website, helping generations of young transgender people identify themselves and learn about the transition process.

“I think a lot of us [trans people] living more interesting, more fun lives than most people. It is our intention,” she said The Independent last year, in what is believed to be the last press interview.

“We are very powerful – in ways that people don’t understand – because of the joy we feel when we are able to do what we do despite the difficulties, and find a place in society where we are truly happy. alive.”

Conway’s death was announced Tuesday by the University of Michigan, where she was a professor emerita, who said she died on June 9.

Michael Hiltzik, columnist for The Los Angeles Times who she had known for 25 years, told him she died of a heart condition, and called him “the bravest person I’ve ever known”.

Born in 1938 in White Plains, New York, Conway grew up in a white, middle-class world that she described as “shocked” by the violence and oppression beneath its “semblance of normalcy”. ‘

After graduating from Columbia University in the early 60s, she moved to Silicon Valley to work on a secret IBM supercomputer project.

She was successful at work, but her personal life was falling apart under the pressure of her repressed identity, and she finally decided to undergo a medical transition.

Then IBM fired her after discovering her transition plans, forcing her to restart her career almost from scratch in a new identity. She remembered that it was very much like being a spy in the Cold War.

“You have to work at a high level pretty quickly, or you’re exposed, and then you betray your whole institution,” she said. The Independent. “But at the same time you have to be kind, not to draw attention … you can’t be angry or show fear.”

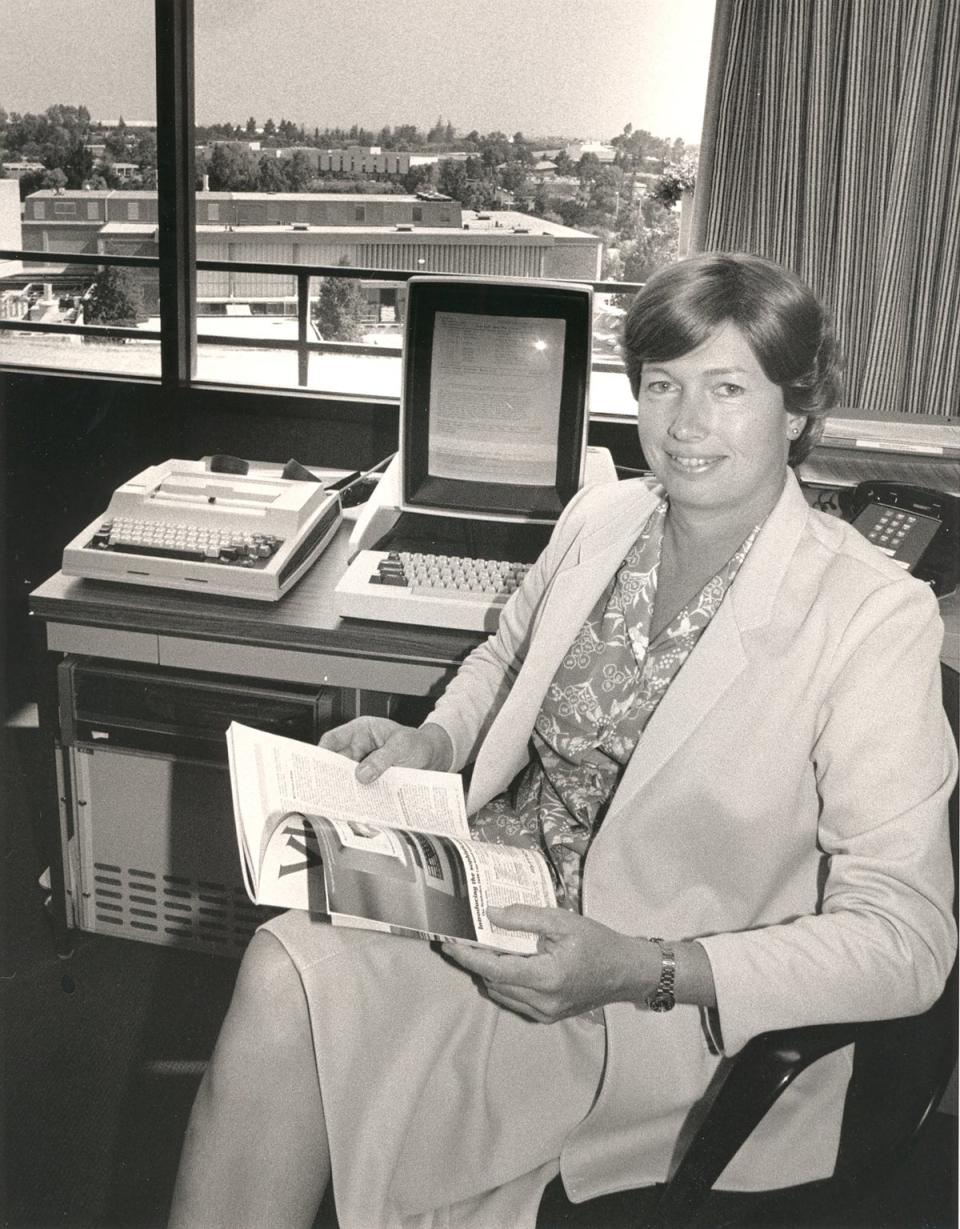

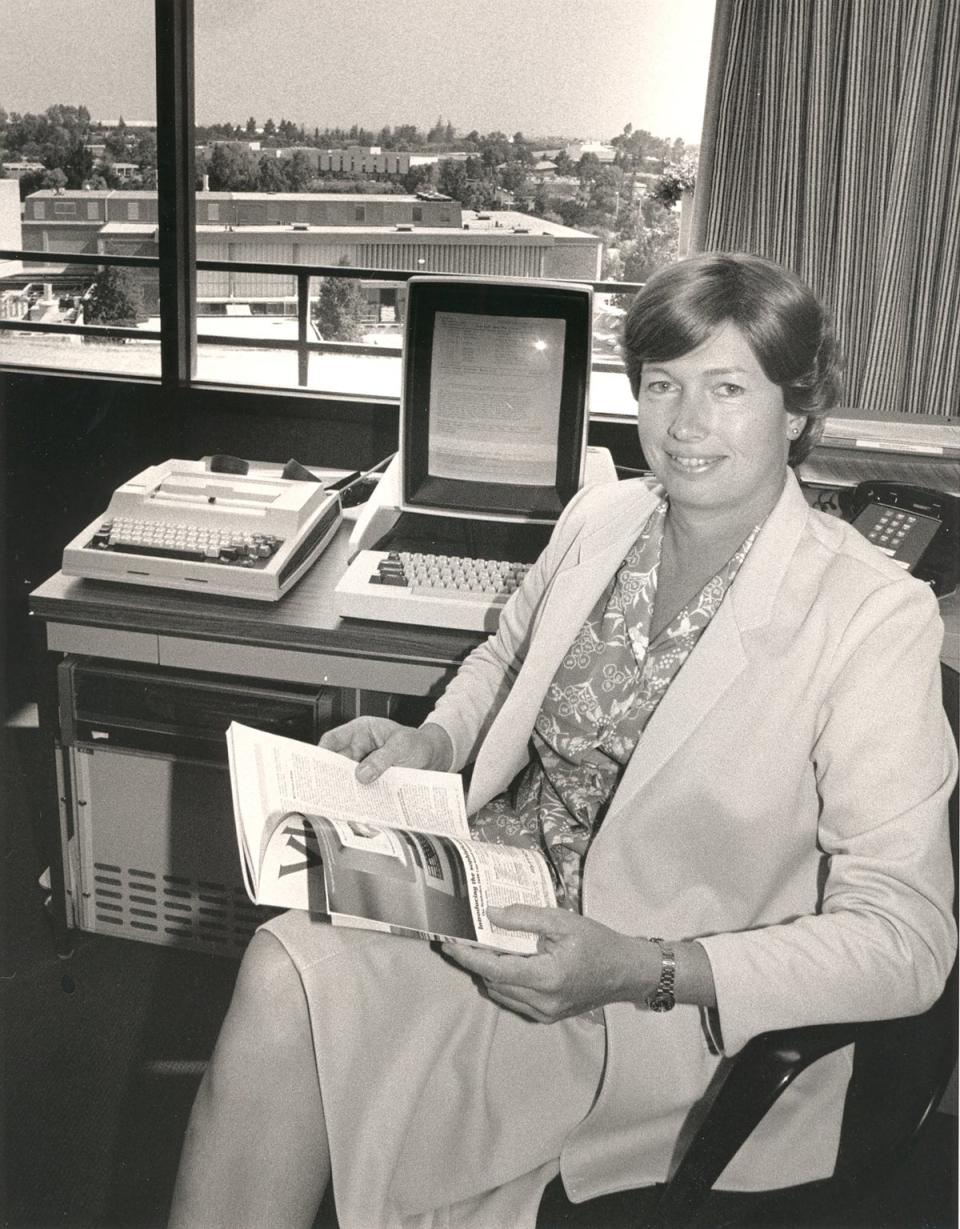

Conway got a job at Xerox’s PARC research laboratory, now famous for innovations such as the computer mouse and the digital desktop interface, where she began collaborating with professor Carver Mead of the California Institute of Technology to solve a serious problem in industry. .

At the time, the number of components that could be squeezed into each microchip was increasing exponentially each year. But the resulting complexity was difficult to manage using traditional, proprietary methods of chip design, hindering the use of this new power.

Conway and Mead’s innovation – called “Very Large Scale Integration”, or VLSI – was to develop a set of rules for clustering components together in standardized blocks, like neighborhoods in a city, simple enough for even a novice engineer to follow .

“It was the freedom of the silicon press,” Conway recalled, “when the designer, the creator, didn’t have to work inside the printing plant.”

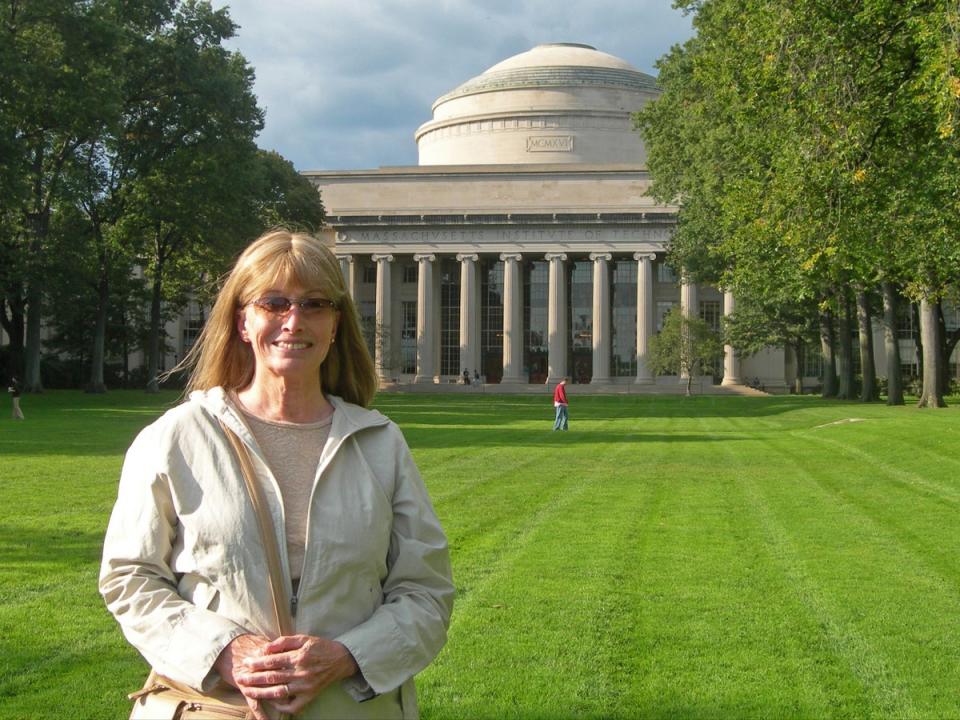

That work led to Conway a job at the military research agency DARPA, and then a professorship at the University of Michigan.

She retired from active teaching in 1998, but continued her love of adventure sports such as rock climbing, motocross, and white water rafting.

In later years, Conway felt she had been unfairly left out of the mainstream history of the computer industry for her invention, and set it aside in favor of her male colleague.

“Mead probably thinks it was 80/20 for him; I think most people, in the long term, will really be 80/20 on me,” she said.

But in recent years more recognition has been given to her work, thanks in part to her own documentation and campaign.

In 2009, she received an award from the engineering trade group, the Institution of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

In 2020, IBM eventually apologized for being shot 52 years earlier. Last October she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame as co-creator of VLSI, 14 years after Mead received the same honor.

In a more personal way, Conway touched the lives of many trans people. For years, her personal website was one of the few places where you could find clear, detailed, unbiased information about the experience of being trans and the transition process – as well as a great example of how transgender people could find happiness and success for transgender people. .

“It was in the early 2000s. My relationship with my girlfriend was falling apart. I had a hard time expressing my feelings when I was younger about the need to move,” says Rebecca, a 51-year-old government worker in Colorado.

“Her site is not the first I found. But when I found it, it opened up a whole new world to me. I knew I wasn’t alone.”

Conway is survived by her longtime husband Charlie Rogers, and her two children, four grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.