New results from the Gaia space telescope suggest that the Milky Way may have cannibalized a small galaxy not too long ago, cosmically speaking. In fact, it appears that the last major collision between our galaxy and another galaxy took place billions years later than previously suspected.

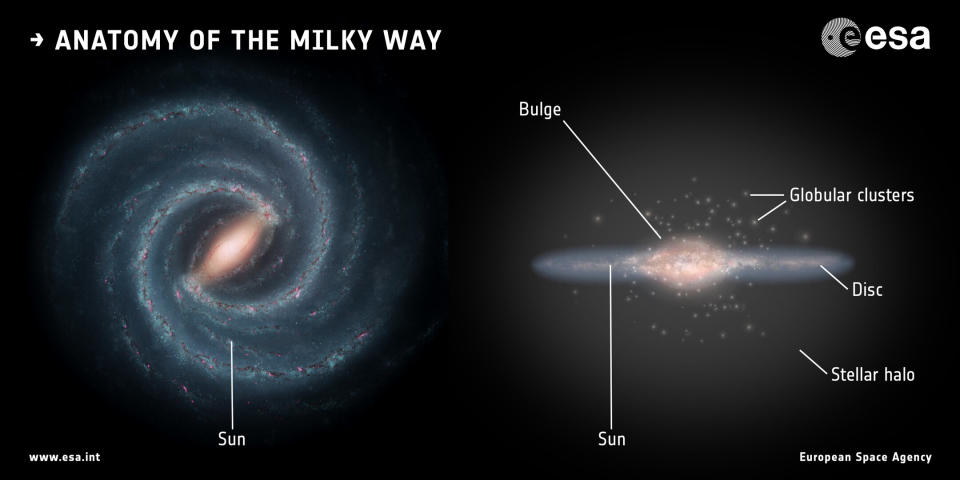

The Milky Way has long been understood to have expanded through a series of violent collisions, which leave smaller galaxies torn apart by the massive gravitational pull of our home spiral solar system. These collisions scatter stars from the depleted galaxy across the halo surrounding the Milky Way’s main disk and its distinctive spiral arms. These rounds of Galactic cannibalism also send “ripples” rippling through the Milky Way that affect different “families” of stars, with different origins, in different ways.

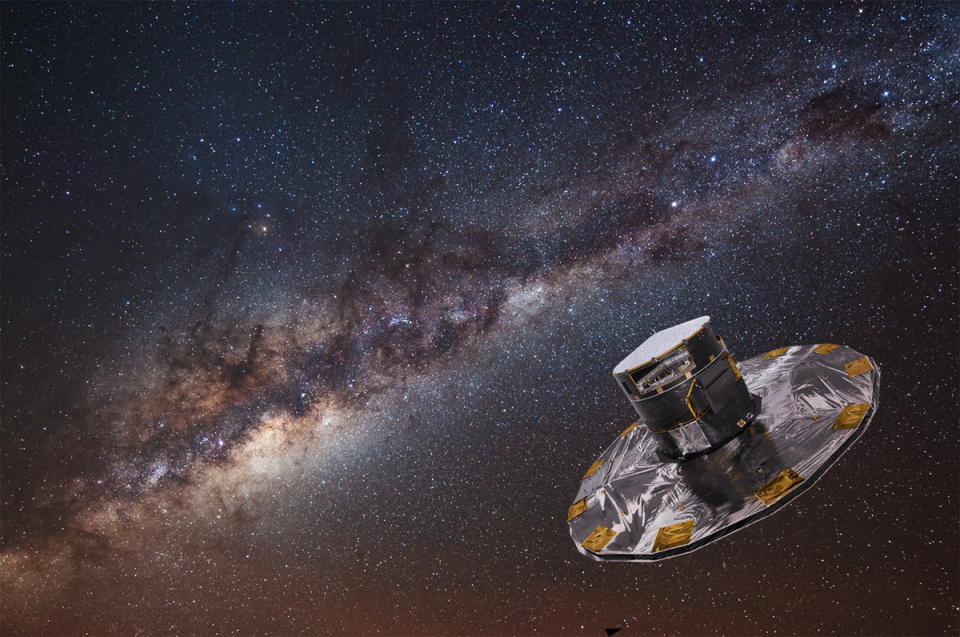

With its ability to pinpoint the position and motion of more than 100,000 stars local to the solar system within the entire catalog of interstellar bodies in monitors, Gaia aims to retell the history of the Milky Way by counting its wrinkles.

Related: In the Milky Way, 3 invading stars are ‘on the run’ — in the wrong direction

“We get wrinklier as we age, but our work reveals that the opposite is true for the Milky Way. It’s a sort of cosmic Benjamin Button, getting less wrinkly over time,” Thomas Donlon, head of a study team on the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and University of Alabama scientist, said in a statement. “By looking at how these wrinkles spread over time, we can track when the last big crash in the Milky Way happened – and it appears that this happened billions of years later than we thought.”

These galactic wrinkles were only discovered by Gaia in 2018; this is the first time they have been extensively researched to reveal the timing of the collision that created them.

Halo stars moving in strange ways free,

Our galaxy’s halo contains stars with strange orbits, many of which are believed to be “stars” of galaxies that once consumed the Milky Way.

Many of those stars are believed to be remnants of the so-called “last big merger,” referring to the last time the Milky Way had a significant collision with another galaxy. Scientists think that this last major collision could involve a giant dwarf galaxy, and the event is known as the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus (GSE) merger. The Milky Way is thought to be infused with stars on orbits that bring them close to the Galactic Center. The GSE event is thought to have occurred between eight and 11 billion years ago when the Milky Way was in its infancy.

Since 2020, Thomas and his team have been comparing the Milky Way’s wrinkles to simulations of how galactic collisions and mergers might have created them. However, Gaia’s observations of these strange orbiting stars – released as part of the space telescope’s Data Release 3 in 2022 – indicate that these odd stellar bodies may have been deposited by another merger event.

“We can see how the shapes and number of wrinkles change over time using these simulated compounds. This allows us to note the exact time when the simulation best fits the size which we see in the real Gaia data of the Milky Way – a method we used for this also new study,” explained Donlon. “By doing this, we discovered that the wrinkle caused by the dwarf galaxy’s collision with the Milky Way was probably around 2.7 billion years ago. We named this event the Virgo Radial Merger.”

“For the wrinkles of the stars to be as clear as they are in the Gaia data, they must have been with us less than three billion years ago – at least five billion years later than previously thought,” team member Heidi Jo Newberg, also of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, said. “A new star wrinkle is created every time the stars swing back and forth through the center of the Milky Way. If they were with us eight billion years ago, there would be so many wrinkles next to each other that we would no longer see them as particular features.”

Examining recent Gaia observations raises the question of whether a truly ancient merger is needed in the early history of the Milky Way to explain the peculiar orbits of some stars in the Galaxy. It also casts doubt on all the stars associated with the previous GSE merger.

“This result – that a large part of the Milky Way only came to us in the last few billion years – is a big change from what astronomers thought until now,” said Donlon. “Many popular models and ideas for the growth of the Milky Way expect a recent head-on collision with a dwarf galaxy of this mass to be very rare.”

The team also thinks that the Virgo Radial Merger brought a family of other small dwarf galaxies and star clusters to our galaxy, all of which would have passed through the Milky Way around the same time.

Future investigation and data from Gaia may show whether any objects associated with the previous GSE event are actually connected to the latest Virgo Radial Merger.

Related Stories

— NASA’s Chandra spacecraft observes a supermassive black hole erupting at the heart of the Milky Way

— Scientists reveal never-before-seen map of Milky Way’s central engine (image)

—The faintest star system orbiting our Milky Way could be dominated by dark matter

This new research is the latest in a trove of results emerging from Gaia data that are rewriting the history of the Milky Way.

This cosmic review is made possible by Gaia’s unique ability to survey large numbers of stars around Earth, allowing the space telescope to compile an unparalleled map of the positions, distances and motions of around 1.5 billion stars to date.

“The history of the Milky Way is constantly being rewritten, in large part, thanks to new data from Gaia,” Donlon concluded. “Our picture of the Milky Way’s history has changed dramatically from even a decade ago, and I think our understanding of these mergers will continue to change rapidly.”

The team’s research was published in May i the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.