Ocean-related tourism and recreation supports more than 320,000 jobs and US$13.5 billion in goods and services in Florida. But swimming in the ocean was not much more attractive in the summer of 2023, when the water temperature off Miami reached as high as 101 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 Celsius).

The future for some jobs and businesses across the ocean economy is less secure as the ocean warms and damage from storms, sea level rise and marine heat waves increases.

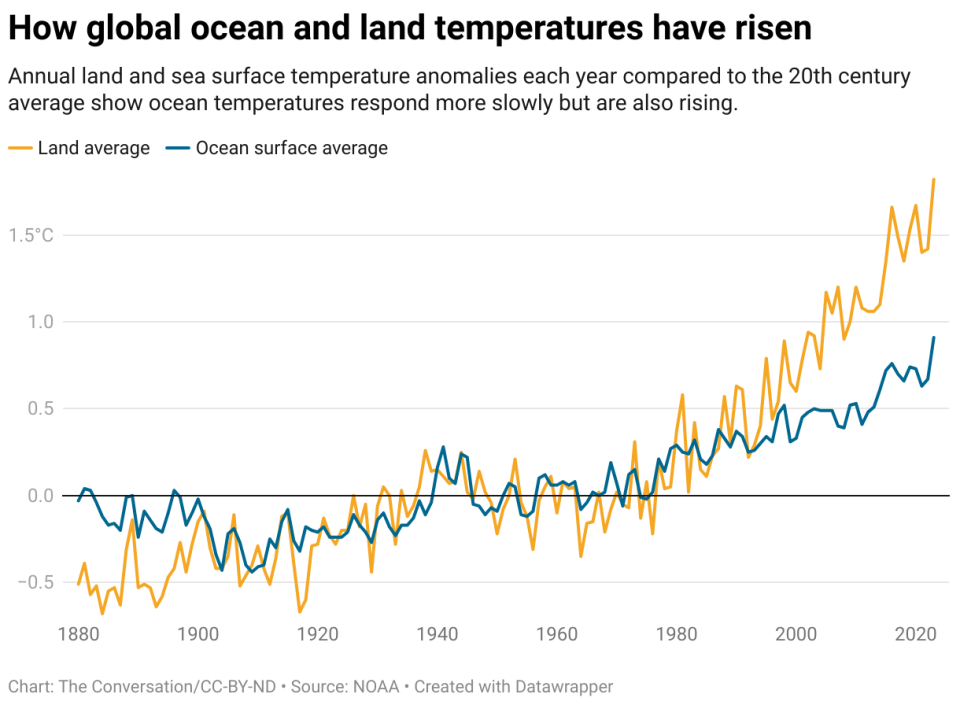

Ocean temperatures have been warming for the past century, and have reached record highs for much of the past year, largely due to the rise in greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. Scientists estimate that more than 90% of the excess heat produced by human activities is in the ocean.

That warming, hidden for many years in data of interest only to oceanographers, is now having profound consequences for coastal economies around the world.

Understanding the role of the ocean in the economy is something I have been working on for over 40 years, currently at the Center for the Blue Economy at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Mostly, I study the positive contributions of the sea, but this has started to change, sometimes dramatically. Because of climate change the ocean is a threat to the economy in many ways.

The dangers of sea level rise

One of the major threats to economies from ocean warming is sea level rise. As water is heated, it expands. Along with meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets, the thermal expansion of the water increased flooding in low-lying coastal areas and threatened the future of island nations.

In the United States, sea levels will soon rise under the siege of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana and Tangier Island in the Chesapeake Bay.

Flooding at high tide, even on sunny days, is becoming more common in places like Miami Beach; Annapolis, Maryland; Norfolk, Virginia; and San Francisco. High tide flooding has doubled since 2000 and is on track to triple by 2050 along the country’s coasts.

Rising sea levels also push salt water into freshwater aquifers, from which water is drawn to support agriculture. The strawberry crop in coastal California is already affected.

These effects are still small and very localized. Enhanced storms at sea level bring much greater effects.

Higher sea levels can make storm damage worse

Warmer ocean water fuels tropical storms. That’s one reason forecasters are warning of a busy 2024 hurricane season.

Tropical storms pick up moisture over warm water and move it to cooler areas. The warmer the water, the faster the storm can form, the faster it can intensify and the longer it can last, resulting in destructive storms and heavy downpours that can even flood cities in far from the coasts.

When these storms now arrive on top of already higher sea levels, the waves and storm surge can greatly increase coastal flooding.

Tropical cyclones caused more than $1.3 trillion in damage in the US from 1980 to 2023, with an average cost of $22.8 billion per storm. Much of that cost has been borne by federal taxpayers.

It’s not just tropical storms. Maine saw what can happen when a winter storm in January 2024 generated tides 5 feet above normal that filled coastal streets with seawater.

What does that mean for the economy?

It is not known what economic damages there may be in the future due to a rise in sea level because it is not known how fast the sea level has risen.

One estimate puts the costs from sea level rise and storm surge alone at more than $990 billion this century, and adaptation measures could reduce this by only $100 billion. These estimates include direct damage to property and damage to infrastructure such as transport, water systems and ports. Impacts on agriculture due to salt intrusion into aquifers that support agriculture are not included.

Marine heat waves leave fisheries in trouble

Rising ocean temperatures are also affecting marine life through extreme events, known as marine heat waves, and more gradual long-term temperature shifts.

In the spring of 2024, a third of the world’s oceans experienced heat waves. Corals are struggling through the fourth global bleaching event on record as warmer ocean temperatures force them to expel the algae that live in their shells and give the corals color and provide food. Although corals sometimes recover from bleaching, about half of the world’s coral reefs have died since 1950, and their future after the middle of this century is bleak.

Losing coral reefs is about more than their beauty. Coral reefs serve as nurseries and feeding grounds for thousands of fish species. According to NOAA estimates, about half of all federally managed fisheries, including snapper and grouper, depend on reefs at some point in their life cycle.

Warmer waters cause the fish to migrate to cooler areas. This is particularly significant for species that like cold water, such as lobsters, which have been steadily migrating north to escape warming seas. A once-strong lobster in southern New England has declined dramatically.

In the Gulf of Alaska, rising temperatures nearly wiped out snow crabs, forcing a $270 million fishery to close completely for two years. A major heat wave extended off the Pacific coast over several years in the 2010s and affected fishing from Alaska to Oregon.

This will not happen soon

The accumulated ocean heat and greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will continue to affect ocean temperatures for centuries, even if countries cut their greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 as expected. So, although ocean temperatures vary from year to year, the overall upward trend is likely to continue for at least a century.

There is no cold water tap we can turn on to quickly return ocean temperatures to “normal”, so communities will have to adapt as the entire planet works to slow greenhouse gas emissions to protecting ocean economies for the future.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by Charles Colgan, Middlebury Institute of International Studies.

Read more:

Charles Colgan receives funding from a number of sources including NOAA and Lloyds of London. He authored the 5th chapter of the National Climate Assessment of the oceans and the 4th chapter of the California Climate Assessment of coasts and oceans.