When Manchester United touch down in Istanbul this week ahead of their crucial Champions League tie with Galatasaray, one thing is certain: the welcome will not be the same as the one they faced 30 years ago.

Back then, members of the media would share a charter plane with the United players. I was there, witness to one of the most extraordinary events in the history of sport. And if the scrum of officers and police who filled the baggage claim area as we filed off the plane that November day in 1993 seemed a little too excited, it was nothing. compared to what we faced in the airport airport. main conference.

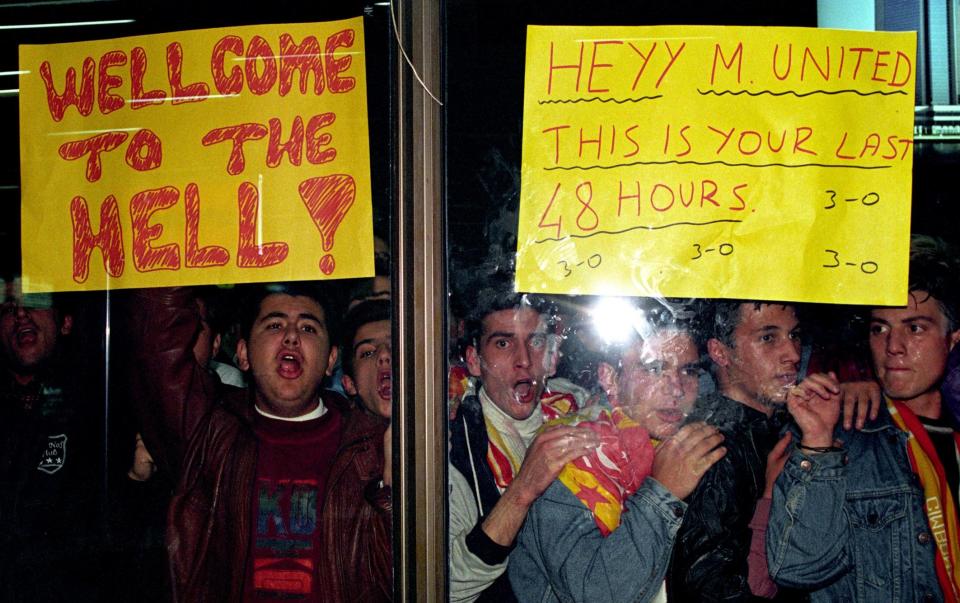

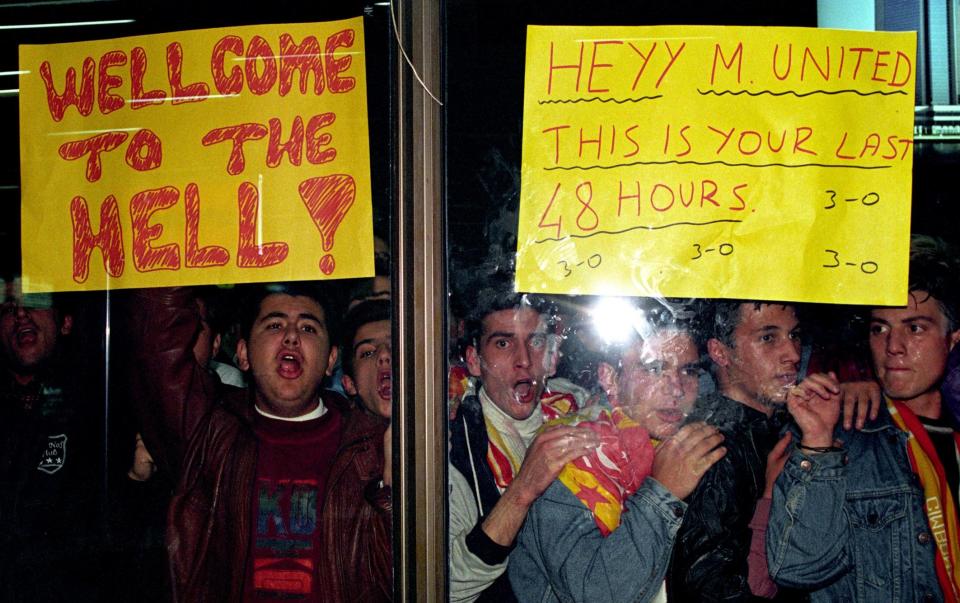

Hundreds of local people gathered there, many urgent signs against the glass barrier scribbled on pieces of cardboard. They were all in English. None of them were friendly.

“Welcome Mr. Cantona. After that goodbye Mrs. Cantona,” was a strange threat. Another thing – “You call us barbarians, but we remember Heysel, Hillsborough” – was much more to the point. But it was the one held by a man that came to define the event.

“Welcome to Hell,” he shouted.

And looking back nearly three decades, it still resonates. While watching football I have never experienced anything close to what happened in Istanbul at that time. It was a football match where the local fans, full of nationalistic intensity, were determined to play their part in ensuring that the noses of European football royalty were bloodied. It’s a claim that’s often made, but the 12th man was really the crowd.

United had arrived in Turkey for the second leg of their Champions League second round tie after complacency in the first leg paid off. In the manner of their current successors in Copenhagen recently, they had raced to a 2-0 lead at Old Trafford and quickly conceded. Galatasaray leveled things at half-time, before taking the lead soon after. Only an 81st-minute equalizer from Eric Cantona saved United’s home record without success in European competition.

So they knew when they touched down in Turkey for the second leg, after conceding so many goals, it would only be a victory. As they walked behind the players as they nervously made their way through the proud welcoming committee, it was clear that this was going to be some challenge.

That evening, Alex Ferguson gave an excellent press conference at the Ali Sami Yen Stadium, convinced that his team could progress. The first question, however, was whether he had ever experienced a riot like the one at the airport.

“Was that a riot, boys?” came the calm reply. “It’s clear there weren’t many of you at the wedding in Glasgow.”

After it was over, I walked the field, surveying the bowl-like sweep of empty open terraces that we were told would be going on the following night. In the center circle was Denis Law, who was a co-commentator on ITV at the time. If he would play here, I asked.

“Yes, for Scotland,” he replied.

And what was the atmosphere like? His answer was succinct.

“S— myself.”

On the evening of the match, the media bus arrived at the ground two hours before kick-off. As we fell out, outside there was no one in sight. Not a soul. It was as if we had come on the wrong day. I asked the bus driver where everyone was. “In,” came the reply. “They’ve been here since 9am.”

They were there all right. When he was inside the stadium, a thumping roar covered the place, like a plane taking off. The front line of the top row was with men beating large bass drums. Behind them there was a constant whirl of firecrackers and flares. A plume of gunpowder smoke extinguished the playing surface. There was no need for chanting: one stand would belt out a cry, another would respond in perfect coordination. And this was more than 90 minutes before kick-off.

It was the only space in the ground I could see in the away section. About 300 United fans stood surrounded by police. It seems that the rest of the 1,200 who traveled were still to come.

With half an hour to go before kick-off, down at the entrance to the underground tunnel leading to the dressing rooms, a phalanx of police formed a turtle of riot shields to protect the United players as they arrived on the pitch to warm up. . Rockets fired from the stands destroyed the shields. A huge chant of “f— you f— you, f— you Manchester” was welcomed.

Just before things started, I saw from the press box the Prime Minister of Turkey Tansu Ciller coming, shouting in front of the crowd. She was unpopular in the polls, and took the opportunity to associate herself with Turkish sporting success.

And it was a success. And the noise was incessant, as if cheers alone would bring their side to victory, all was out in an ear-bleeding cacophony. As the noise around them boomed, United looked indecisive, distracted.

Exasperated by UEFA’s cap on foreign players at the time – which included Irish, Welsh and Scottish internationals as foreigners in England teams – Ferguson was forced to tinker with his preferred line-up, leaving Mark Hughes . Without the bull-like front, United looked toothless. In fact Peter Schmeichel’s excellent double save from Hakan Sukur (whose popularity at the club propelled him into a later career as a member of the Turkish giants) did not keep them there.

With three minutes remaining and the game still goalless, the ball was sent off the field, among the substitutes, photographers and police. Although, between them, he refused to give it back to a United player. When Cantona saw the lead, in a way that would become familiar to Selhurst Park three years later, Cantona ran 20 yards and knocked the ball out of the arms of the policeman who was handling it.

When the 90-minute whistle blew (no modern extra time for a referee who looked like he wanted to go to the dressing room in one piece) chaos ensued. Galatasaray defied all odds, defeated the one-time champions on away goals and progressed to the next round.

Hakan ran to the crowd waving his shirt over his head. He never did it, went below the human pyramid. Thousands flocked to the field, skipping and dancing joyfully. It turned out that most of the invaders were police. Their dogs – some wearing Galatasaray’s red and yellow collars – snapped at the red-shirted United players as they made their disconsolate way to the tunnel. On the way, Cantona said something to the referee and was shown a red card. As he left the pitch with captain Bryan Robson, he was hit in the back of the head by a policeman, apparently still angry at the dropped kick. As Robson turned to reinterpret, he was wearing a riot shield.

I went out to see what was happening. Word spread the famous aggregate win. From all over the city, thousands flocked to the ground to take part in the celebrations. A lorry drove over the overpass that bypassed the stadium with half a dozen young people on its bonnet, dancing. Everywhere car horns were blaring, pyrotechnics filled the sky. It was a riot. After I asked a local in English, he suggested I return inside pronto. “You’re not safe out here,” he said.

Back inside, I went down the tunnel, where I was told Ferguson would speak to the press. It was filled with police, jostling and shoving. I made my way to the United dressing room, from where I expected to hear the sound of broken crockery. But the manager was more subtle. He had allowed silence to make his speech. For the first time that evening, everything was quiet, stilled in defeat. Eventually Ferguson appeared for a brief press huddle.

“We didn’t play well enough. In the end it was desperation. Shambles,” he said. “I don’t intend to make any excuses. The biggest loss tonight was our European experience.”

Although as European experiences go, this was something to remember. As I made my way back onto the pitch, the 300 or so United United supporters were the only ones left in the ground. They were surrounded by police as if they were a threat to national security. I called up one “where are the others?”

“Catch,” came the reply.

And indeed some were picked up. Apart from the many refused entry on the ground despite having tickets, or the hundreds who were deported before the start, six people were held in an Istanbul prison for the next 28 days, until they were unceremoniously sent back to Blighty. Their crimes? Being in the sights of a police force for the most part they seem eager to do their job to improve their team’s opportunities.

For the locals, the hangover was significant. After a long evening of celebrations, the casualty list included two people killed by bullets that fell from guns being fired in the air, another man who fell drunk under a train and dozens who were taken to hospital after being injured by a cascade of fireworks .

As it turned out, the result gave no hint of what lay ahead: in the next stage of the competition, Galatasaray finished at the bottom of their group; United, embarrassed by their relegation, went into contention of their own by winning the domestic double. It’s safe to say that consolation is unlikely to be available should Erik ten Hag and his team suffer the same discomfort on Wednesday.