Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

The Great Pyramid of Egypt and other ancient monuments at Giza are located on a remote strip of land on the edge of the Sahara Desert.

The inhospitable location has long puzzled archaeologists, some of whom have found evidence that the Nile River flowed near these pyramids in some capacity, facilitating the construction of the landmarks that began 4,700 years ago.

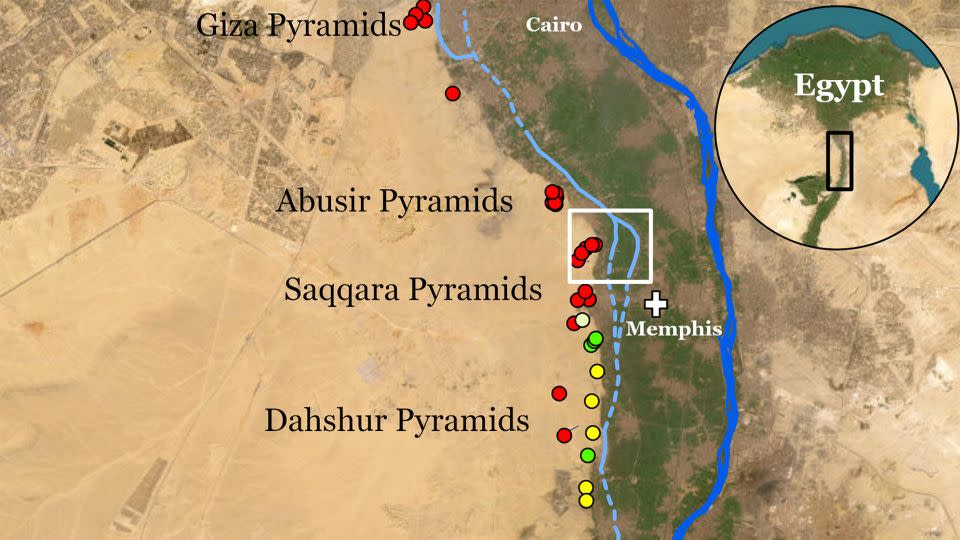

Using satellite imaging and analysis of sediment cores, a new study published Thursday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment mapped a dried-up 64-kilometer (40-mile) branch of the Nile, long buried under farmland and desert. . .

“Although many attempts have been made to reconstruct the early waterways of the Nile, they have mostly been based on collections of soil samples from small sites, resulting in only fragmentary parts of the ancient Nile channel systems being mapped,” said lead author of the study. Eman Ghoneim, professor and director of the Space and Drone Remote Sensing Lab at the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences.

“This is the first study to provide the first map of an ancient, long-lost branch of the Nile.”

Ghoneim and her colleagues refer to this extinct branch of the Nile as Ahramat, which is Arabic for pyramids.

The ancient waterway would have been about 0.5 kilometers wide (about one-third of a mile) with a depth of at least 25 meters (82 feet) — similar to the contemporary Nile, Ghoneim said.

“The sheer size and extended length of the Ahramat Branch and its proximity to the 31 pyramids in the study area strongly suggest that a functional waterway is very important,” said Ghoneim.

She said that the river would have played a central role in transporting the ancient Egyptians the huge amount of building materials and workers needed to build the pyramids.

“Also, our research shows that many of the pyramids in the study area have (a) causeway, a ceremonial raised path, that runs perpendicular to the course of the Ahramat Branch and ends directly on a river bank.”

Hidden tracks on a lost waterway

Traces of the river are not visible in aerial photographs or in imagery from optical satellites, Ghoneim said. In fact, she came across something unexpected while studying radar satellite data of the wider area of ancient rivers and lakes that could reveal a new source of groundwater.

“I’m a geomorphologist, a paleohydrologist who looks at landforms. I have this kind of trained eye,” she said.

“As I was working with this data, I noticed this really obvious branch or kind of riverbank, and it didn’t make sense because it’s a long way from the Nile,” she said.

Born and raised in Egypt, Ghonim knew about the cluster of pyramids in this area and had always wondered why they were built there. She applied to the National Science Foundation for further investigation, and geophysical data taken at ground level using ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic tomography confirmed that it was an ancient arm of the Nile. Two long land cores taken by the team using drilling equipment showed sandy sediments consistent with a river channel at a depth of about 25 meters (82 feet).

It is possible that “countless” temples could still be buried beneath the agricultural fields and desert sands on the banks of the Ahramat River, according to the study.

It is not yet clear why this branch of the river dried up or disappeared. Sand was probably swept into the region during a period of drought and desertification, silting up the river, Ghoneim said.

The study showed that when the pyramids were built, the geography and rivers of the Nile were significantly different from those that exist today, said Nick Marriner, a geographer at France’s National Center for Scientific Research in Paris. He was not involved in the study but has researched the history of the Giza river.

“The study completes an important part of the past landscape puzzle,” Marriner said. “By putting these pieces together we can get a clearer picture of what the Nile floodplain looked like at the time of the pyramid builders and how the ancient Egyptians used their surroundings to transport building materials for their efforts significant construction.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com