Five hundred years ago, in a mountainside sea ford in southeast Alaska, Tlingit hunters, with bone harps, eased their canoes through floating chunks of ice, stalking seals near the Sít Tlein (Hubbard) glacier. They must have looked nervously at the broken face of the glacier, knowing that ice floes could thunder down and endanger the boats – and their lives. As they approached, they would ask the seals to give themselves as food for the people and they spoke to the spirit of Sít Tlein to release the animals from his care.

Tlingit elders in the Alaska Native village of Yakutat today describe their ancestors’ daring pursuit of harbor seals, or “tsaa,” and the people’s appreciation of the spirits of the mountains, glaciers, oceans and animals of their subarctic world.

Long ago, they say, the migrating clans of the Eyak, Ahtna and Tlingit tribes settled Yakutat fjord as the glacier receded, moving their hunting camps over time to stay near the ice floe rookery where the animals give birth every spring. The heads of the clans managed to avoid the debt of harvesting too soon, too much debt or waste, which reflected the innate values of respect and balance between people and nature.

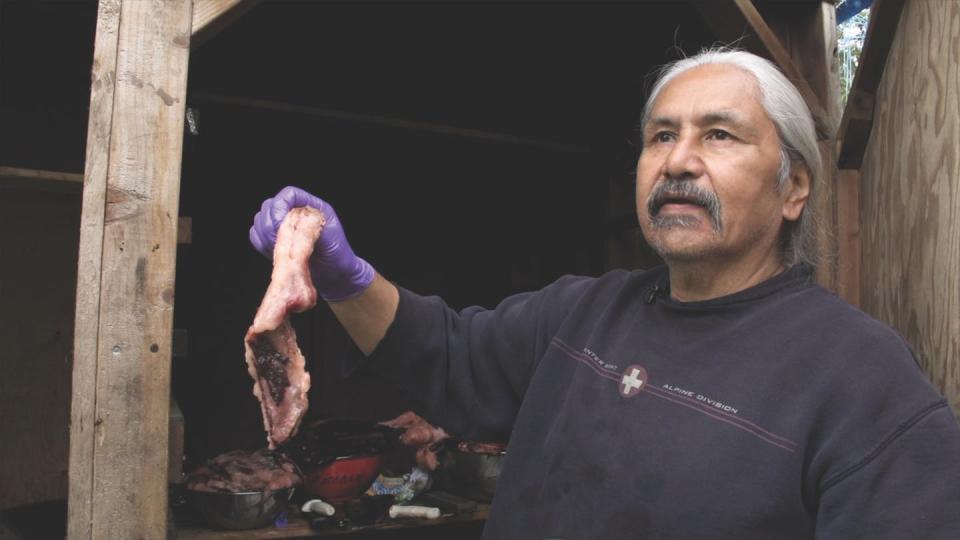

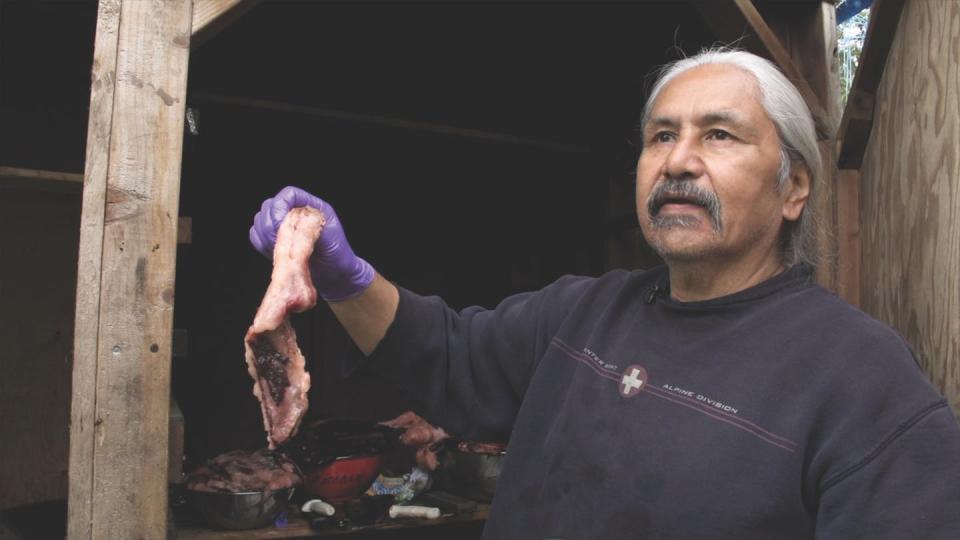

Now, 300 Tlingit residents of Yakutat continue this way of life in a modern form, harvesting more than 100 fish, birds, marine mammals, land game and various plants for subsistence use. Harbor seals are the most important, their rich meat and blubber prepared using traditional recipes and eaten at daily meals and commemorative potlatch feasts.

But the community is facing a crisis: the significant decline in the seal population of the Gulf of Alaska due to commercial hunting in the mid-20th century and the animals’ failure to recover due to warming sea waters. To protect the seals and their way of life, residents are turning to traditional ecological knowledge and ancestral conservation practices.

We are an Arctic archaeologist who studies human interactions with the marine ecosystem and a Tlingit tribal historian of the Yakutat Kwáashk’i Kwhite clan We are two leaders of a project that examined the historical roots of the case.

Our collaborative research, which brought together archaeologists, environmental scientists, Tlingit elders and the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe, has been published as the book “Laaxaayík, Beside the Glacier: Native History and Ecology at Yakutat Fjord, Alaska.” In this report, we detail the changing way of life of the Indigenous people and the evolving relationship with their glacial environment over the past 1,000 years. To do so, we combined indigenous knowledge of history and ecology with scientific methods and data.

Sealed ancestral

According to oral tradition, the Gine built the village of Tlákw.aan (“old town”) on an island in Yakutat fjord.x Kwáan, an Ahtna clan from the Copper River who migrated across the mountains, intermarried with the Eacá and traded ceremonial copper shields for land in their new territory. They waited on the rich resources of the fjord and hunted the seal rookery near the retreating glacier, located there a few miles to the north.

Today Tlákw.aan is a cluster of clan house foundations in a quiet forest clearing, and our excavations there in 2014 were aimed at learning more about the lives of the inhabitants and their use of seals before Western contact.

Radiocarbon dating indicates that Tlákw.aan was built around 1450 AD, aligning oral accounts with geologists’ reconstruction of the glacier’s location at that time. Artifacts confirm the Ahtna and Eyak identities of the inhabitants. Sealed items found at the site include harpoon points, stone oil lamps, skin scrapers and copper inlaid knives. Harbor seal bones are common, with more than half from young animals taken at the rookery.

The site reflects the aboriginal conditions – an abundant seal population, dependent on seals for meat, oil and skins, and sustainable hunting at the glacial rookery.

Commercial sealing effect

The US purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 disrupted traditional sealing at Yakutat. To meet the global demand for seal skins and oil, the Alaska Commercial Company supplied rifles to Alaska Native communities and recruited them to kill thousands of harbor seals.

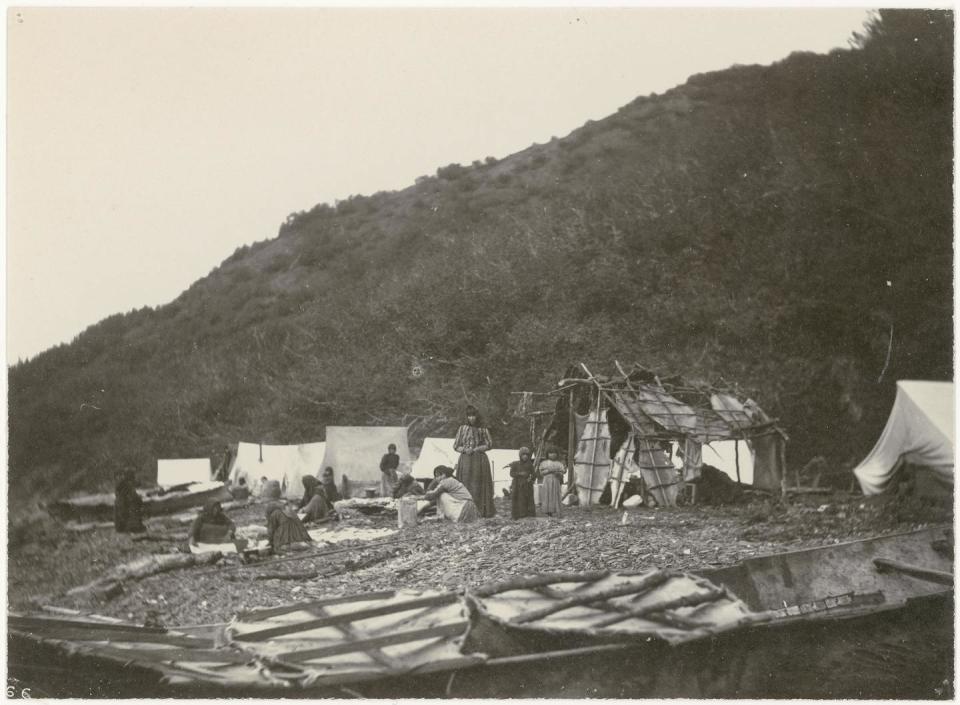

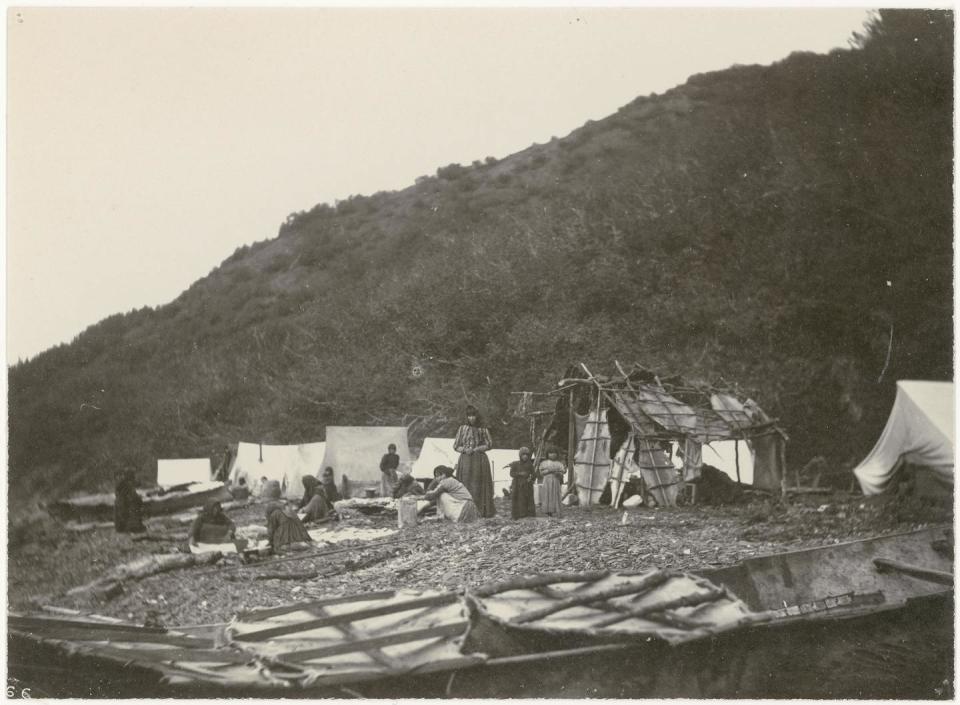

Yakutat was a major hunting center for the new industry from about 1870 to 1915, and each spring the entire community would move from their main winter village to hunting camps near the glacier. Men shot seals and women prepared the skins, smoked the meat and blubbered it into oil. In the fall, the men rowed sea canoes, laden with seal products for trade, to the Alaska Commercial Company’s post in Prince William Sound.

We have compared the historical data and accounts of the elders of this era with archaeological evidence from Keik’uliyaa, the biggest camp. The scale of the enterprise is evident in photographs taken in 1899 which show long rows of canvas tents, smokehouses, seal skins drying on frames, hunting canoes on the beach and women barking piles of seal carcasses. Inside the rock perimeter of the tents, we found glass beads, rifle cartridges, nails, glass containers and other trade items that reflect the changing culture of the community and its incorporation into the capitalist market system.

Overtaxed commercial hunting prevented the seals from reproducing, leading to a population crash in the 1920s. This cycle repeated itself in the 1960s when world prices for skins jumped and Alaska Native hunters took hundreds of thousands of harbor seals in the Gulf of Alaska, exceeding the sustainable yield. The seal population has declined by 80%-90%.

Although commercial sealing ended in 1972 with the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the seals never recovered. The days when the ice floes were “black with seals,” as Yakutat elder George Ramos Sr. remembered. over, maybe forever. Ocean warming driven by global climate change and the unfavorable cycle of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation have reduced the number of fish important in the seals’ diet, and increased the prospects for their return.

Caring for seals and the community

In response, Yakutat Natives changed their diet and greatly reduced hunting, taking 345 seals in 2015 – about 1 per person – compared to 640 in 1996. Very little hunting is now done on the ice floe rookery, which allows the seals to raise their pups. without interfering.

The community collaborates with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Alaska Native Harbor Seal Commission to monitor and co-manage the herd, leveraging their indigenous expertise on seal behavior and ecology. They were also active in efforts to protect the seal rookery from intrusion by cruise ships.

The people of Yakutat are recommitting to ancestral principles of responsible care and spiritual care for seals, seeking to ensure the survival of the species and the continuation of the life-sustaining native sealing tradition.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

Written by: Aron L. Crowell, Smithsonian Institution and Judah Dax̱ootsú Ramos, University of Alaska Southeast.

Read more:

Aron L. Crowell receives funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Park Foundation, the Sealaska Heritage Foundation, and the Smithsonian Institution.

Judith Dax̱ootsú Ramos receives funding from the Cook Inlet Region, Alaska Native Heritage Center.