It might be hard to imagine, but once again, dinosaurs did not affect their world. When they first arrived, they were just small two-legged carnivores overshadowed by a diverse range of other reptiles.

How did they come to rule?

My colleagues and I recently studied the fossilized bones of the earliest known dinosaurs and their nondinosaur competitors to compare their growth rates. We wanted to find out if the early dinosaurs were somehow special in the way they grew – and if that might have given them a leg up in their rapidly changing world.

Before dinosaurs – the great death

Life on Earth flourished 250 million years ago. Dinosaurs were yet to emerge. Instead, giant amphibians and sail-supported reptiles known as therapsids flourished.

But within the span of geological time, within about 60,000 years, scientists estimate that 95% of all living things became extinct. Known as the Permian extinction or the Great Dying, it is the largest of the five mass extinction events on Earth.

Most scientists agree that extensive volcanic activity in modern Siberia, which covered millions of square miles with lava, caused this almost complete die-off. The resulting noxious gases and heat combined to push global temperatures up significantly, leading to ocean acidification, loss of oxygen in ocean waters and profound ecosystem collapse, both on land and both in the ocean.

Only a lucky few survived.

The survivors and their descendants

In an ecological vacuum after the mass extinction, on the stage of the healing World, the ancestors of the dinosaurs emerged for the first time – together with the ancestors of today’s frogs, salamanders, lizards, turtles and mammals. It was the beginning of the Triassic Period which lasted from 252 million years ago to 201 million years ago.

Collectively, the creatures that survived the Great Death were not particularly noted. One group of animals, called Archosauria, began with relatively small and simple body plans. They were flexible eaters and could survive in a wide range of environmental conditions.

Finally, archosaurs split into two tribes – one group including modern crocodiles and their ancient relatives and the second group including modern birds, as well as their dinosaur ancestors.

This second group walked on their toes and had large leg muscles. They also had additional connections between their spine and hip bones that allowed them to move efficiently in their new life.

Rather than competing directly with other archaea, this ancestral group of dinosaurs appears to have taken advantage of different ecological niches – perhaps by eating different foods or living in slightly different geographical areas. But early on, the dinosaur archosaurs were much less diverse than the crocodile ancestors they lived alongside.

Slowly, the dinosaur lineage continued to evolve. It took thousands of years before the dinosaurs became abundant enough for their skeletons to show up in the fossil record.

The oldest known dinosaur fossils come from an area in Argentina now known as Ischigualasto Provincial Park. There are rocks from about 230 million years ago.

The dinosaurs of Ischigualasto include the three groups of dinosaurs: the meat-eating theropods, the ancestors of the giant sauropods and the plant-eating organisms. They include Herrerasaurus, Sanjuansaurus, Eudromaeus, Eoraptor, Chromogisaurus, Panphagia and Pisanosaurus.

These early dinosaurs make up only a small fraction of animals found from that time period. In this ancient world, the crocodile archosaurs were on top. They had a wider range of body shapes, sizes and lifestyles, which made them superior to the early dinosaurs in the diversity race.

It wouldn’t be until closer to the end of the Triassic Period, when another volcanism-induced mass event occurred, that the dinosaurs got their lucky break.

The late Triassic extinction killed 75% of life on Earth. It reduced the crocodile-like tusks but left the early dinosaurs largely untouched, paving the way for them to dominate.

Before long, dinosaurs went from less than 5% of the animals on earth to more than 90%.

Bones tell the story of growth

My colleagues from the Universidad Nacional de San Juan, Argentina, and I wondered whether the rise of the dinosaurs might have been underpinned, in part, by how fast they grew. We know, through microscopic study of fossilized bones, that later dinosaurs had rapid growth rates – much faster than today’s reptiles. But we didn’t know if that was true for the earliest dinosaurs.

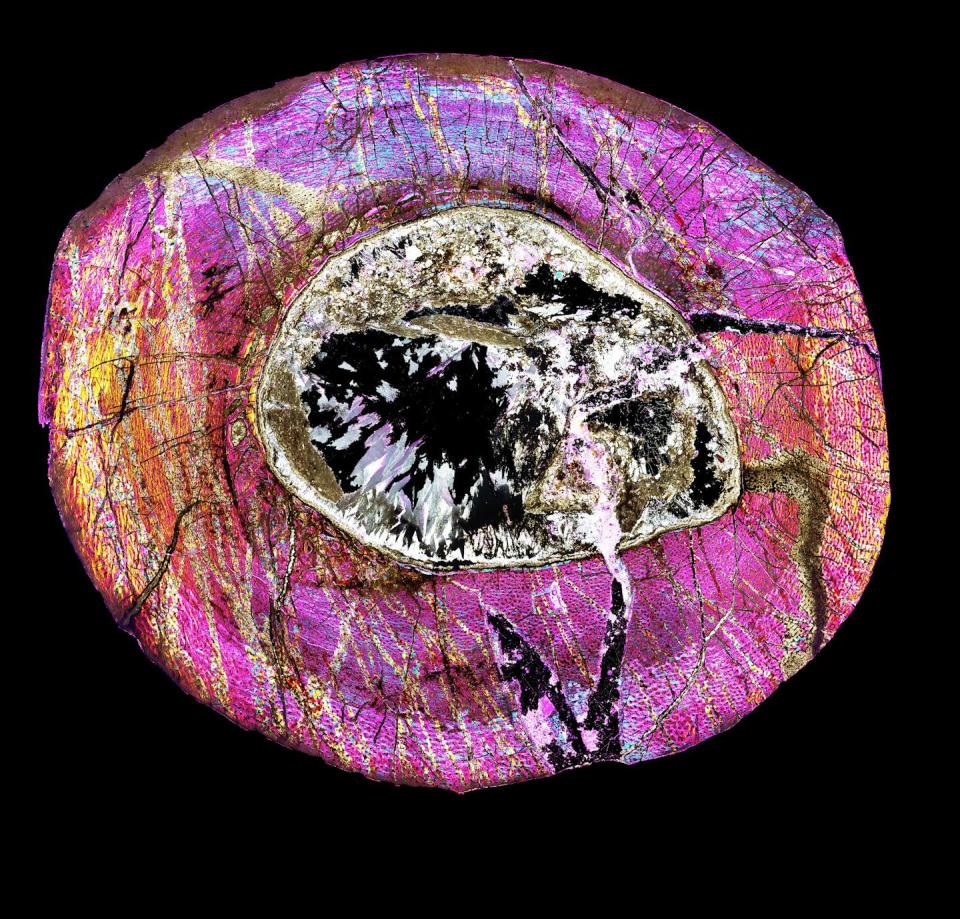

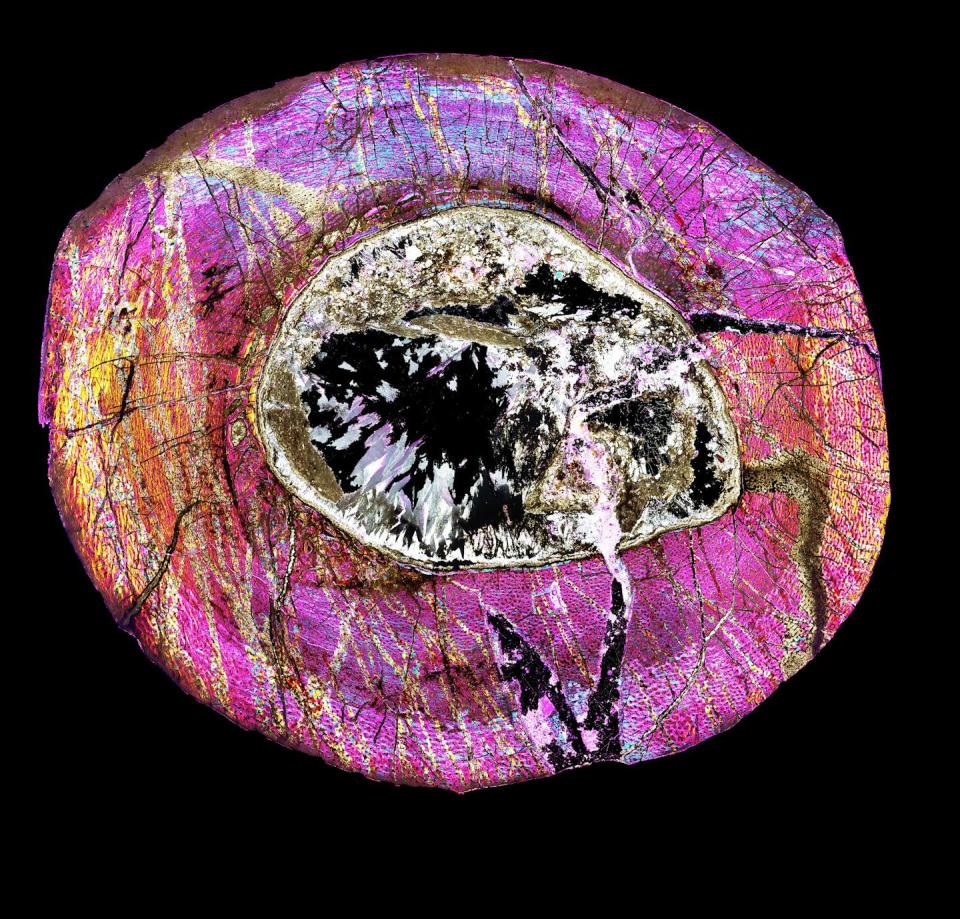

We decided to examine the microscopic patterns preserved in thigh bones from five of the earliest known dinosaur species and compare them to those of six nondinosaur reptiles and one early mammal relative. All the fossils we studied came from the 2 million year interval within the Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina.

Bones are an archive of growth history because, even in fossils, we can see the spaces where blood vessels and cells perforate the mineralized tissue. When we look at these elements under a microscope, we can see how they are organized. The slower growth occurs, the more organized the microscopic features will be. With faster growth, the most disorganized is the microscopic features of the bone marrow.

We discovered that early dinosaurs grew continuously, not stopping until they reached full size. And indeed they had increased growth rates, on par with and, sometimes, even faster than those of their descendants. But so did many of their nondinosaur counterparts. Most of the animals living in the Ischigualasto ecosystem appear to have grown rapidly, at rates more similar to those of living mammals and birds than of living reptiles.

Our data allowed us to see the subtle differences between closely related animals and those that occupy similar ecological niches. But most of all, our data show that rapid growth after mass destruction is a great survival strategy.

Scientists still don’t know exactly what enabled dinosaurs and their ancient ancestors to survive two of the world’s most widespread extinctions. We are still studying this important interval, looking at details such as legs and bodies built for efficient, straight movement, possible changes in the way the earliest dinosaurs may have breathed and the way they grew. We think it’s probably all these factors, along with luck, that allowed dinosaurs to eventually rise and rule.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Kristi Curry Rogers, Macalester College

Read more:

Kristi Curry Rogers receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the David B. Jones Foundation.