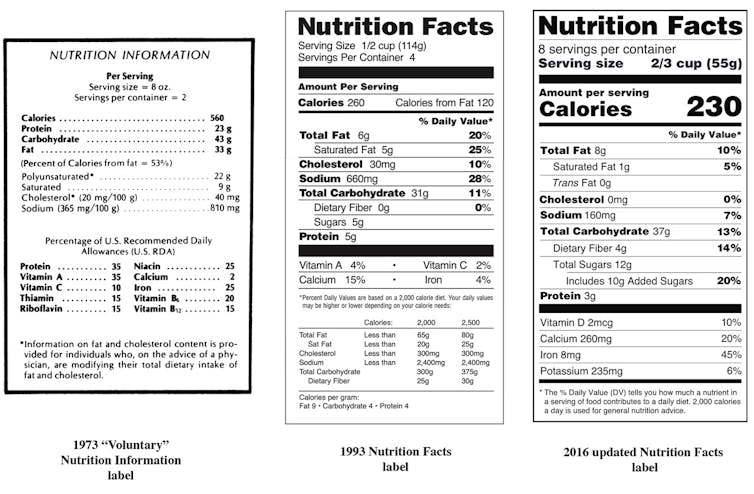

The Nutrition Facts label, that black and white information box found on almost everything packaged food product in the USA since 1994has recently become an icon of consumer transparency.

From Apple’s “Privacy Nutrition Labels” that reveal how smartphone apps handle user data, to a “Clothing Facts” label that standardizes the ethical disclosure of clothing, policy advocates across industries invoke “Nutrition Facts” as a model for consumer empowerment and enabling socially responsible markets. . They argue that intuitive information solutions could solve a wide range of market-driven social ills.

BIGGER: The Wistar Institute opens a research center dedicated to finding a cure for HIV

But this ordinary product label has a complicated legacy.

I study food regulation and diet culture and became interested in the Nutrition Facts label while researching the history of Food and Drug Administration policies on food standards and labeling. In 1990, Congress passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, mandating nutrition labels on all packaged foods to help address growing concerns about rising rates of chronic illness associated with unhealthy diets. . The FDA introduced its “Nutrition Facts” panel in 1993 as a public health tool that empowered consumers to make healthier choices.

The most obvious purpose of the Nutrition Facts label is for consumers to learn about the nutritional properties of food. In practice, however, this label has done much more than just inform one. It also encodes a wide range of political and technical compromises on how to translate food into nutrients that meet the diverse needs of the American public.

Where does ‘% Daily Values’ come from?

The daily value, or DV percentages, on the label do not come from the same source. This reflects different public health goals for the label.

The recommended values for micronutrients such as vitamins are based on Recommended Dietary Allowances, or RDAs, from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Vitamin RDAs were developed out of historical concerns with undernutrition and meeting minimal needs.

Daily value percentages for macronutrients – carbs, fats and proteins – are based on the US Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines. DVs for macronutrients registered a new concern about overeating and a focus on “negative nutrition” encouraging maximum levels of intake.

DVs represent two fundamentally different concerns. The numbers represent a floor for micronutrients: the basic vitamin requirements that a child should meet to avoid malnutrition. On the other hand, the numbers for macronutrients are an upper limit: a target upper limit that adults should avoid if they want to prevent future health problems from eating too much high-sodium or fatty food.

Why 2,000 calories?

The FDA used nearly 2,350 calories as a baseline to calculate daily values, as it was the recommended population-adjusted caloric requirement for Americans four years of age and older. But after pushback from concerned health groups that the higher baseline would encourage overconsumption, the FDA settled on 2,000 calories.

FDA officials felt that this figure was less likely to be “misrepresented as a single target since a round number implies less specificity.” This means that 2,000 calories is not a goal for most label-reading American consumers. Instead, it’s an example of public health care about collective risk — what one scientist called “treating sick populations and not sick individuals.”

By choosing a round number that was easy to do math with, and a calorie count below the American average, FDA officials favored practicality and utility over accuracy and objectivity. They would recommend the lower calorie baseline of 2,000, they reasoned, which would offset Americans’ tendency to overeat and do more good for the population as a whole.

Who decides serving sizes?

According to the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, serving sizes should reflect “amounts normally used.”

In practice, this involves routine negotiations between the FDA, the US Department of Agriculture – which also sets serving sizes for nutritional guidance tools such as the MyPlate – and food manufacturers. Each researches consumer expectations and food consumption data, taking into account how food is prepared and “usually eaten.”

Serving sizes are also determined by product packaging. For example, a can of soda is generally considered a single-serve container so only one serving is made, regardless of how many fluid ounces it contains.

What’s in a name?

The label was almost called “Nutritional Values” or “Nutrition Guide” to emphasize that Daily Values were recommendations. Then FDA Deputy Commissioner Mike Taylor proposed “Nutrition Facts” to sound more legally neutral and scientifically objective.

The new design – black Helvetica text, positioned against a white background, using indented subgroups and hairlines for readability – and the authoritative boldface title helped establish “Nutrition Facts” as an easily recognized government brand.

This led to imitators in other policy areas: first “Drug Facts” for over-the-counter medicines, then consumer protection initiatives in various tech industries, such as the Federal Communications Commission’s “Broadband Facts” and “AI Nutrition Facts.”

The Nutrition Facts panel has remained largely consistent since the 1990s, despite some updates such as adding lines for trans fats in 2002 and for added sugars in 2016 to reflect evolving public health priorities.

New ways to calculate the facts

Establishing the Nutrition Facts label required building a completely new technical infrastructure for nutrition information. New measures, test procedures and standard references were needed to translate the diverse American diet into a consistent set of standardized nutrients.

A key player in the development of that technical infrastructure was the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. In the early 1990s, the AOAC Task Force developed a food triangle matrix that divides foods into categories based on their proportion of carbs, fats and protein. The intention was to determine suitable ways to measure nutritional properties such as the amount of calories or sugars, as the physical properties of the food would affect how well each test worked.

Legacy of the Nutrition Facts label

Today, public-private collaborations have furthered this transition of foods into simplified nutrient profiles through the compilation of nutrition facts. The USDA FoodData Central provides a comprehensive database of nutrient profiles for individual ingredients used by manufacturers to calculate Nutrition Facts for new packaged foods. This database also powers many diet and nutrition apps.

The analytical tools developed for the Nutrition Facts label helped create the foundational information infrastructure for today’s digital diet platforms. But critics argue that these databases reinforce an overly reductive view of food as simply the sum of its nutrients, without taking into account how food is affected by its various forms – such as its moisture, fiber content or porous structures – the way the body metabolizes nutrients.

Indeed, many nutrition researchers concerned about the negative health effects of ultra-processed foods now speak of a food matrix to emphasize precisely the opposite of what the AOAC seeks with its food triangle: the need for a holistic understanding of how health food.

Surprisingly, perhaps the biggest impact of the Nutrition Facts label was driving the food industry to reformulate products to achieve attractive nutrient profiles – even if consumers weren’t reading the labels closely. Although envisioned as an educational tool, I believe the Nutrition Facts label has worked practically with market infrastructure, reshaping the food supply to meet changing dietary trends and public health goals long before consumers find those foods in the supermarket.

Xaq Frohlich, Associate Professor of History of Technology, Auburn University

This article from The Conversation is republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.