Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Well-preserved fossils of large ancient reptiles called pterosaurs have shown that some species flew by flapping their wings, while others soared like vultures, according to a new study.

Pterosaurs ruled the skies during the age of dinosaurs and met the same deadly fate 66 million years ago after an asteroid strike triggered a massive event. Some of the largest pterosaur species were giants that reached the size of small airplanes and stood as tall as a giraffe, leading researchers to question whether pterosaurs could even fly.

The newly discovered fossils preserved 3D structures within the delicate wing bones, which are usually found as flattened pancakes within rock layers.

CT scans of the fossils have provided a rare insight into the inside of the wing bones of two species of pterosaurs, including one new to science.

The results of the research, published Friday in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, revealed a surprising and unexpected finding: Not only could giant pterosaurs fly, but different species adapted different flight styles.

Intact fossils provide a window into the past

The fossils date back 66 million to 72 million years in the late Cretaceous Period. The team first found the specimens in 2007 at two sites in what is now northern and southern Jordan, buried in deposits from an ancient land known as Afro-Arabia that once included Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. .

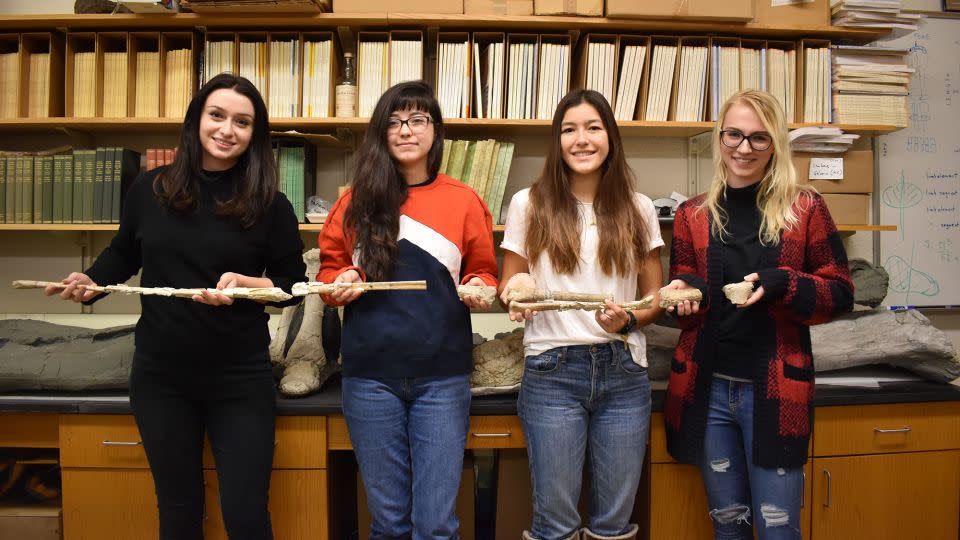

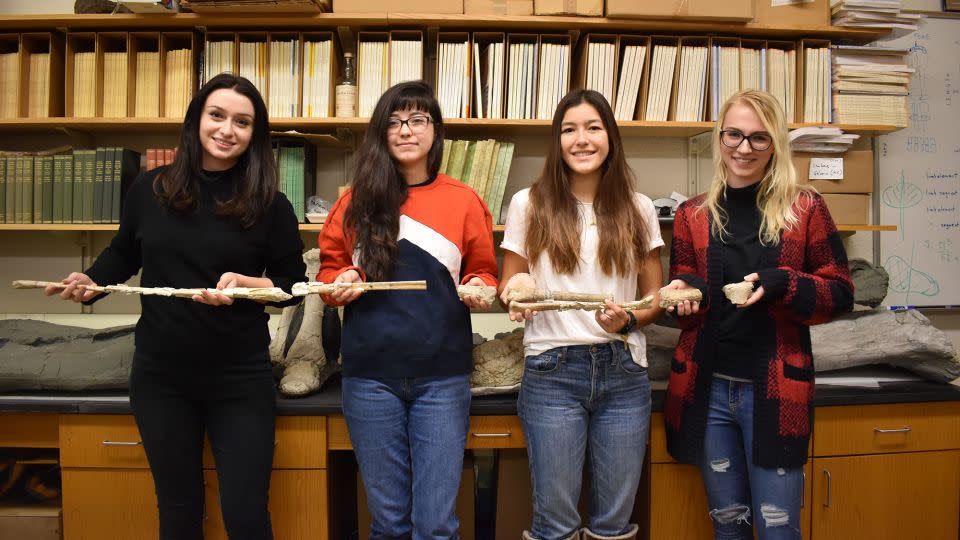

After understanding the underlying structures, the research team was keen to analyze them using high-resolution CT scans, said lead study author Dr Kierstin Rosenbach, a paleontologist and researcher within Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the National University of Ireland, Galway. Michigan at Ann Arbor.

Some of the fossils belonged to a giant pterosaur called Arambourgiania philadelphiae and provided the first look at its bone structure, as well as confirming that it had a wingspan of 32.8 feet (10 meters). The team noticed a series of ridges that went up and down her hollow humerus bone.

The other fossils were part of a pterosaur new to science called Inabtanin alarabia. It is named after the large grape colored hill, Tal Inab, where it was found. The name combines the Arabic words “inab,” for grape, and “tannin,” for dragon, and “Alarabia” refers to the Arabian Peninsula.

Inabtanin alarabia is one of the most complete pterosaur fossils ever found from this region, according to the researchers. The reptile was smaller than Arambourgiania with a wingspan of 16.4 feet (5 meters).

When the researchers scanned the fly bones, they realized they were looking at a completely different structure than that of Arambourgiania.

Among the flight bones for Inabtanin was an internal structure of tendons, or reinforcing rods that helped them fly. These are not unlike those found in the wing bones of modern birds that flap their wings to fly, Rosenbach said.

In contrast, the inside of Arambourgiania’s wing bones had spiral ridges similar to the inside of vulture wing bones, which are thought to resist the forces of lift.

“The strings found in Inabtanin were visually stunning, though not unusual,” Rosenbach said in a statement. “The ridges in Arambourgiania were completely unexpected, we weren’t sure what we were seeing at first.”

Variation of pterosaur flight

The largest modern flying bird is the Andean condor, which has a wingspan of 9 feet (about 2.8 meters). But pterosaurs had huge wingspans that could reach 16.4 to 39.3 feet (5 to 12 meters).

“They are the largest animals that can fly,” Rosenbach said of the extinct reptiles.

Finding that pterosaurs adapted different flight styles is exciting because it sheds light on the behaviors and lifestyles of these ancient reptiles, the researchers said.

“I think they would look very different if we could watch them fly side by side,” Rosenbach said. “Inabtanin would flap its wings like modern birds, but Arambourgiania was more likely soaring with flapping wings, like a vulture or a pelagic seabird.”

The fossils did not provide any insight into how the pterosaurs got off the ground, but the team is using their findings to find out how these different styles of flight developed.

“The variation in internal structure probably reflects the response of the bones to mechanical forces applied to the wings of the pteroosaurs,” said study coauthor Jeff Wilson Mantilla, curator and professor at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

The researchers can’t say for sure which style came first, but when looking at birds and bats, flapping is the most common, Rosenbach said. And even birds that soar or glide need some flapping to help them get up in the air and maintain flight.

Flying styles likely evolved due to a combination of factors, such as the pterosaurs’ environment, their body shape and size, and how they hunted prey, the authors said.

The scientists found both fossils in areas where there was once a large shallow sea, so each species may have adapted different behaviors to forage in the same environment, Rosenbach said.

“This leads me to believe that flight is hitting the default condition, and that the soaring behavior might have evolved later if it would have been advantageous to the pterosaur population in a particular environment; in this case the open ocean,” she said.

An emerging look at ancient flight

Pterosaur wing bones had to cope with the stresses of flight while still being light, which is why the hollow bones show different strengthening structures within their bone walls, said Michael Benton, professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Bristol in the UK. United.

“This is a nice study of the structure of the vertebrae of two large pterosaurs, a large one and a giant one,” said Benton, who was not involved in the research. “How pterosaurs could be light enough and still strong enough to fly has always been a mystery, especially the numerous examples that were far larger than any known bird. This paper helps provide the answer.”

The authors of the study believe that their findings add new evidence to the ongoing debate among paleontologists about whether the largest pterosaurs could fly.

“The internal bone structure of these fossils suggests that they experienced the mechanical forces associated with flight,” Rosenbach said. “We can think of these results as one piece in the puzzle of growing evidence that large pterosaurs retained the ability to fly at very large body sizes.”

The research team is eager to get a chance to see more scans of pterosaur bones and find out how the newly discovered pterosaur Inabtanin relates to the rest of the ancient reptiles.

“There is growing evidence that pterosaurs were more diverse near the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event than we previously thought,” Rosenbach said via email, referring to the mass extinction of dinosaurs and the most most of life on earth. “This shows that the extinction was catastrophic compared to a slow extinction process for large reptiles.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com