As global temperatures keep increasing, making storms harder, some researchers say the Saffir-Simpson scale, which measures hurricane wind speed, does not adequately address the hazards of extreme storms. In a new study, scientists explored a hypothetical expansion of the scale to include Category 6, and found that such a designation could help people focus on worsening risks.

In a new study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers found that the scale, which was created in the early 1970s and is still used to define hurricane categoriesthere is “weakness”: topping out in Category 5 even though “the destructive potential of the wind increases exponentially.”

The hurricane categories run from 1 to 5, with a Category 5 hurricane having wind speeds of 156 mph or stronger—enough to produce “catastrophic” damage, which NOAA says could result in “complete roof failure on many residences and industrial buildings” as a result. such as extended power outages.

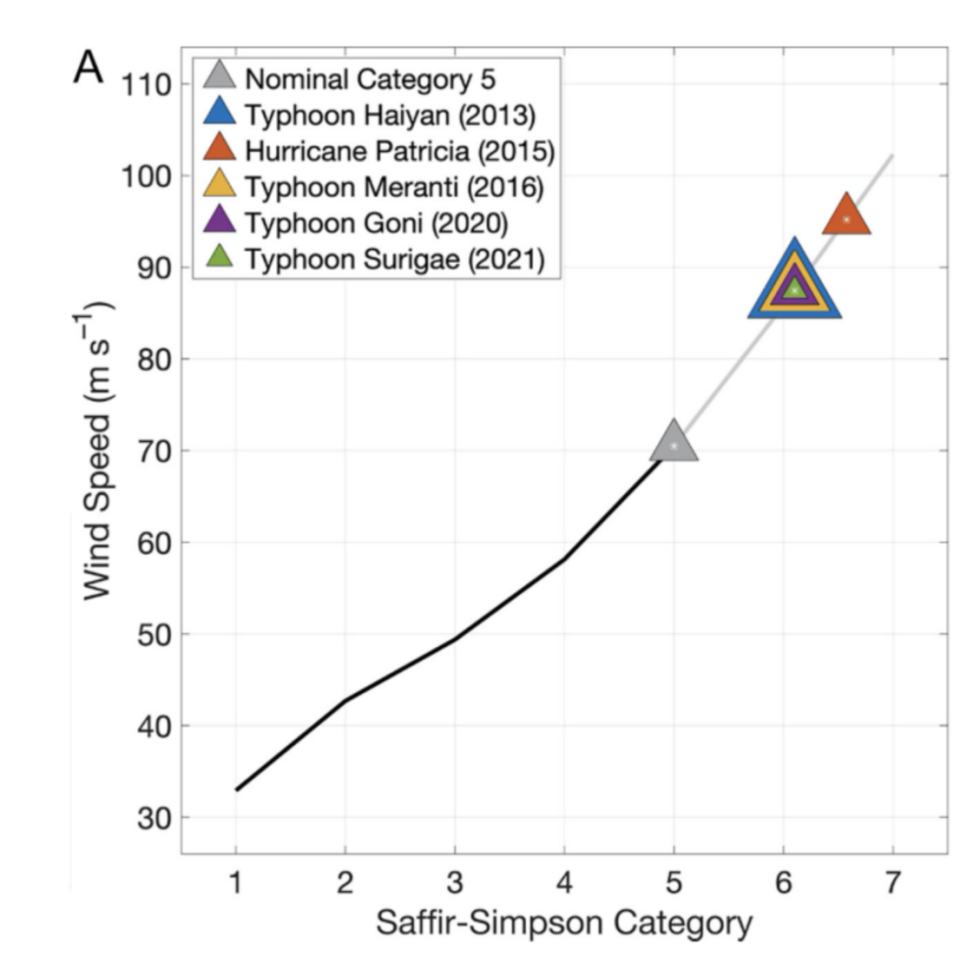

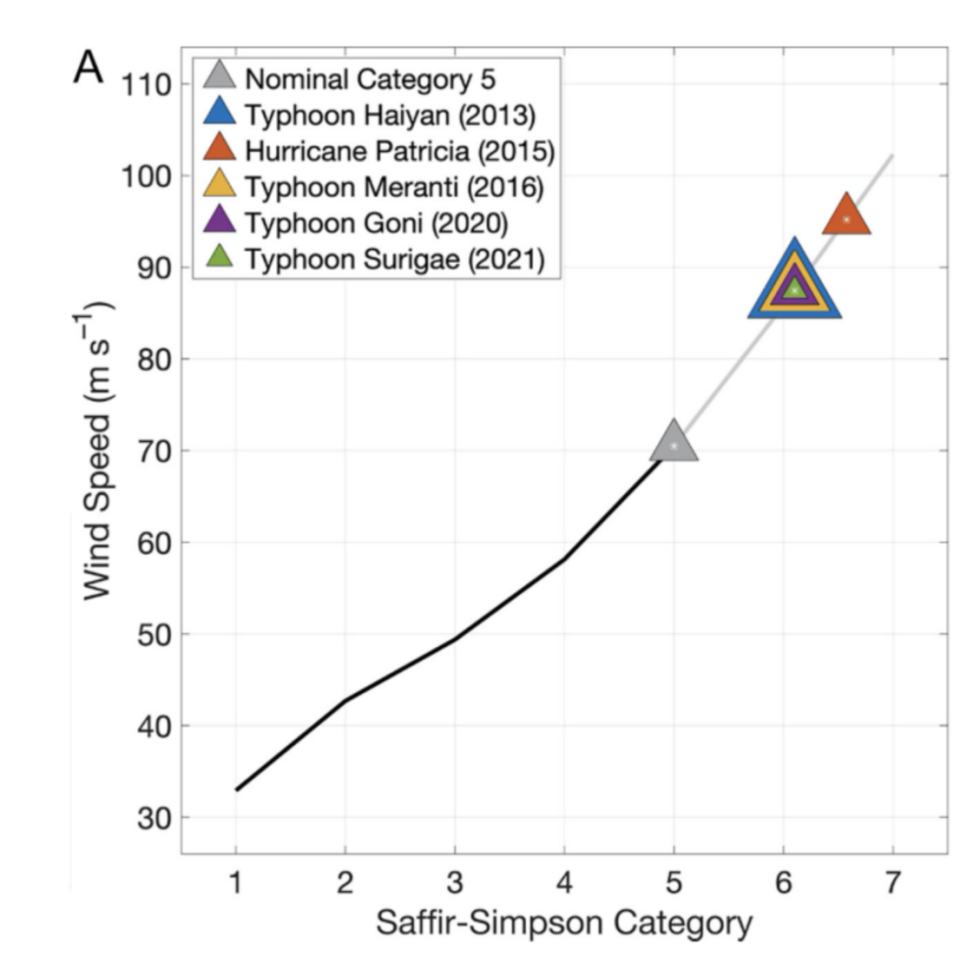

Michael Wehner, the lead author of the latest research, told CBS News that there have been several hurricanes in recent years with winds that far exceed 156 mph — and that it may be absolutely necessary. new category. He and fellow researcher James Kossin looked at the potential impact of expanding the scale to limit wind speeds of 192 mph in Category 5, and to designate any hurricanes or cyclones above that. as Category 6, to help inform people about the following. risks.

“We found that there were five storms greater than this hypothetical Category 6, and all of them were recent, since 2013,” Wehner told CBS News.

It was the most intense of those five storms Hurricane Patrick, which peaked with wind speeds well over 200 mph before making landfall in Mexico as a Category 4 in October 2015. Patricia “severed at a rate rarely seen in a tropical cyclone,” according to the National Hurricane Center. NOAA reported that the storm hit maximum winds of 215 mph, nearly 60 mph faster than the lower bar of the Category 5 designation.

The other storms of hypothetical Category 6 strength occurred in the Western Pacific, the study says. Typhoon Haiyanthat hit the Philippines in 2013, “the costliest storm in the Philippines and the deadliest since the 19th century, long before any significant warning systems,” the study says.

The researchers also looked at a “state-of-the-art” climate measurement system that analyzes potential intensity — “basically a speed limit for how fast the highest winds could be in a perfect storm,” Wehner said.

“Our motivation here was the link between climate change – that the warming of the atmosphere, of the globe, from the burning of fossil fuels – to hurricanes and tropical cyclones,” Wehner said, adding that he and Kossin consider themselves “fairly conservative climate scientists.”

“Because climate change increases temperature and humidity – which are the energy sources for a hurricane or tropical cyclone – this speed limit would be expected to increase,” he said. “And indeed it does.”

Wehner and Kossin found a “significant” increase in wind speeds since 1982, saying in their study that wind speed records are likely “as the planet continues to warm.”

They also ran simulations based on different global warming scenarios, and found that the risk of seeing what would be Category 6 storms “has increased significantly and will continue to increase with climate change.”

This is not the first study to look at a hypothesis expansion of the Saffir-Simpson scale. In 2019, former hurricane hunter and NOAA meteorologist Jeff Masters wrote that the current hurricane categories are “inadequate.” He proposed expanding the scale to include Category 6, starting with winds of 180 to 185 mph, and Category 7, to be used for storms with winds of at least 210 mph.

“Any move to expand the Saffir-Simpson scale would have to come from the National Hurricane Center (NHC), however, and there is little support for such a move from the experts there,” he wrote in a blog post for Scientific American. “From a public safety/warning standpoint, the NHC experts I’ve heard from believe that including a category 6 would not do much good, as a category 5 hurricane is already considered catastrophic.”

Wehner admitted the Saffir-Simpson Scale was widely criticized for being only a hurricane category decision. The scale is based on wind speed alone, and while that is a critical measure in determining storm risk, it does not take into account the potential destruction caused by the size of the storm or the storm surge and flooding that can occur. could be there. The Wehner study does not address those other hurricane factors.

Those hurricane risks should be better incorporated when explaining storm risk, Wehner said.

“One number doesn’t really describe the overall risk of an incoming hurricane if you’re on the road,” he told CBS News. “You need to know what kinds of dangers you are exposing yourself to.”

The researchers said in their paper that they are not specifically recommending changes to the scale, but are looking to “raise awareness that the wind hazard risk from storms currently designated as category 5 has increased and will continue to increasing.” Adding a sixth category to the scale could help raise awareness of the expected changes in storm wind strength in the coming years, and how that, on top of other hazards, could lead to impact on communities, they said.

“The stronger the wind, the stronger the storm surge. And there will be a lot more rain regardless,” Wehner said. “…From the context of global warming, trying to put a single number on what is the increased risk from global warming that is a longer-term type of danger, we think this scale is fine.”

Another criticism Wehner said that the expanded scale got the question, “If we add a Cat 6, does a Cat 3 storm look bigger?”

“And the answer is, ‘Of course he does,'” he said. “…Just because the worst storms are worse doesn’t mean bad storms aren’t bad.”

Killer Mike appeared in handcuffs during Grammys after winning 3 awards

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell: Interview 2024 60 Minutes

Candice Bergen on Truman Capote’s amazing Black and White Ball