When you make a purchase through links on our article, Future and its syndicate partners may earn a commission.

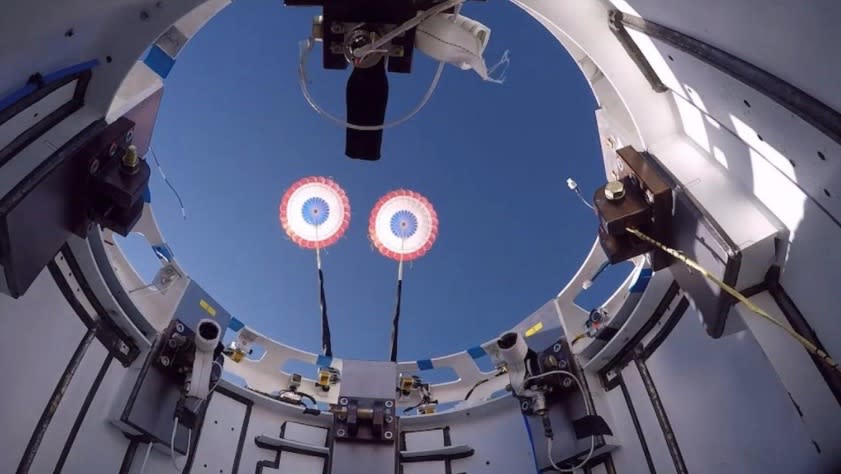

Starliner, without its astronauts, will make a twilight landing on Earth by parachute on September 7 after fully detaching from the International Space Station on the evening of September 6.

NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams launched on Crew Flight Test, the first human launch of a Boeing Starliner, on June 5. They were supposed to re-enter and land on the spacecraft, but NASA chose to transfer them to the SpaceX Crew Dragon. for landing in February 2025 after problems developed with the Starliner’s propulsion system during combustion that could not be resolved.

A number of design changes were made to Starliner when a parachute problem was discovered in 2023. Ahead of CFT’s launch, Space.com spoke with NASA’s Jim McMichael. McMichael is a senior technical integration manager in the agency’s commercial crew program space operations mission directorate.

Take a Boeing Starliner!

You can build your own Boeing Starliner space capsule with this Metal Earth Boeing CST-100 Starliner 3D Model Kit, available for $10.95 at Amazon.

Related: The 1st Boeing Starliner crew to return to Earth without astronauts on September 6

The interview took place at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center near Orlando shortly before the Starliner launch attempt was aborted on May 6 following technical issues with the United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket; troubleshooting of Starliner’s helium leak delayed the launch until June 5. At the time of the interview, NASA and Boeing thought Starliner would land with astronauts on board.

This interview has been edited for clarity and condensing.

Space.com: What are your job duties?

McMichael: It is basically the last “other duties as assigned job.” It’s areas that need a little extra integration, a little extra help. I move around. I’m really a newbie. I have only been on this program for about two years. But most of that time, I’m working mainly on the parachutes.

My previous background is that I worked a bit on the SpaceX Dragon. In my previous positions at NASA, I spent about 10 years on the [Lockheed Martin] Development of the Orion parachute [for moon missions]. So, “parachute” is kind of in my blood.

Space.com: What makes a Starliner parachute similar and different from a Dragon or Orion?

McMichael: The Boeing Starliner parachute system is a scaled-down version of the Orion system. It’s a little smaller – because the weight of the capsule is a little less – but apart from that, the architecture is very similar. Both Boeing and Orion have a heat shield in the front, and both are parachuted. The architecture is a little different in terms of how [the removal] is done. But when you manage to do that, we have two drogue parachutes on each of them that are fired with mortars. Those are cut free. We have three pilot parachutes on each that pull out three mains on each.

The architecture [on Dragon] something a little different, in that they fire the drogues with a mortar, and then they just hold the drogues on one outfit. When they are ready to transition from drogues to pilots, they don’t cut the drogues and fire […] instead, they release the drogues and then the drogues themselves raise the larger parachutes, to deploy.

Related: See SpaceX’s Crew Dragon parachute in action in this epic video compilation

Space.com: So, if I can roll back about a year, to when you discovered that the parachutes needed further adjustments, I might call that the Parachute 1.0. So today, is it a completely different parachute? Or is it a sort of adjustable parachute?

McMichael: The issue we found last summer was called “soft links”. They are what tie the suspension lines. They are a primary link, and carry the main load. When we discovered that those were an issue, we had already completed all of our quality testing, if you will. So the trick was we need to upgrade those, make them stronger and change to improve the soft links.

But we didn’t want to invalidate all the testing we had done up to that point. You get your data by testing the same system over and over again. So we didn’t want to start over because we didn’t want to throw away all that quality testing history.

McMichael: To be clear, the soft links in the system — those still had a positive margin. [In other words]they would not be expected to fail. It’s just that the margin wasn’t as high as we wanted it to be because they are a critical element. We make a slightly higher margin on those because we have people on board. The soft links are the main load path; if you lose soft links, you lose the ability to carry a load. On other pieces of the parachute […] You could blow out a panel, you could blow out a bunch of panels, it wouldn’t affect the parachute at all. It would not change its performance.

So that was a change we made. Then while we were working — the four most expensive words in the English language — there was also a new design change on the table to change the hanging line at the skirt to the parachute. But again, the trick was, we wanted to make sure we didn’t invalidate all the expensive, hard, long testing we’d done in the past with these changes.

So these were minor changes. We did a lot of ground testing there to verify its strength. Then, we’ve also done an airdrop test afterwards… It’s the law of unintended consequences that sometimes you can get bitten. We wanted to make sure that these small changes would not have any unintended consequences.

Space.com: How are you thinking ahead for Starliner-1, the first operational crewed mission expected in 2025?

McMichael: Parachuting takes a lot of time to make. They’re a long, long lead item, if you will, and then they’re put into the spacecraft pretty early on—so, the Starliner-1 parachute is the same as the parachutes we’re flying today. That said, there is a tiny work delta to be done between CFT and Starliner-1.

The suspension lines themselves – the material as we buy it – you buy it in many manufactures. Manufacturing suspension line material for Starliner-1 is quite different than for CFT, so we have to check to make sure that the suspension line material is at least as strong and verify our edge again with the material new suspension line.

Spoiler alert: We have the details [from pull testing]. We have seen that the new suspension lines for Starliner-1 are actually quite a bit stronger. So we know we’ll be fine. We haven’t dotted the I’s and crossed the T’s on the paperwork yet.

Related: What’s next for Boeing Starliner after its 1st crewed flight test?

We will carefully inspect the CFT parachutes. That’s one of the things we’ll look at in our flight images. We’ll look at all the pictures from the ground – we also have ground video, so we’ll see how the slides were deployed. That doesn’t sound very scientific, but that’s a huge part of watching parachute performances: one of the big things we do is watch them deploy.

Then when we recover them in the desert, we will inspect them carefully: every joint, every piece of clothing, every parachute. We will check to make sure there are no changes or anything unexpected. Often, you end up with small tears, rips, torn things in a parachute. And that is absolutely right. It is fully expected. So, we will do all those inspections, but [so far]we do not expect any changes.

RELATED STORIES:

— The 1st Boeing Starliner crew to return to Earth without astronauts on September 6

— Boeing Starliner astronauts will return home on SpaceX Dragon in 2025, NASA confirms

— This is what the Boeing Starliner astronauts are doing on the ISS as NASA works on its journey home

Space.com: So when you’re on the parachute team, you don’t rest until the end.

McMichael: We joke that this whole spacecraft is just a way to deliver parachutes into orbit. But you’re right, we’re the last — way back in the day, Apollo did a video when all the testing around the Apollo parachute system was over. And the title was “Project Apollo: The Last 5 Miles Home.”

We take that seriously, because the parachutes are the last five miles home. The world is in the windows. We deploy the main at 8,000 feet [2.4 km]. In the whole scheme of being in space, 8,000 feet is pretty close to the ground. We deploy the main and it’s front and center: the big beautiful picture of the crew module hanging from the main parachutes.

So yeah, we don’t rest until we get the drogues […] and then when the mains are raised — we get full inflation on all three mains — then we can start breathing.