Imagine you are visually impaired and you are completing an online job application using screen reader software.

You get through half of the form and then you come across a question with drop-down options that the screen reader can’t access because the online form doesn’t meet accessibility standards. You are stuck. You cannot submit the application, and your time has been wasted.

Assistive technologies such as screen readers go a long way in closing the gap between people who are blind or visually impaired and their sighted peers. But the technologies often hit roadblocks because the information they are designed to work with – documents, websites and software programs – do not work with them, making the information inaccessible.

There are 8 million people who are blind or visually impaired in the US Over 4.23 million of them are of working age, but only about half of that working age population is employed. Historically, employment rates for blind or partially sighted people have been much lower than for the general population.

The vast majority of jobs across all industries require digital skills. Assistive technologies such as screen readers, screen magnifiers and braille receivers allow people who are blind or visually impaired to succeed in school and in the workplace.

Assistive technology has improved, and new technology for blind or partially sighted people is being developed all the time. Technology developed by large tech companies for the general population often incorporates built-in accessibility features such as VoiceOver in the iPhone and Narrator in Windows, both text-to-speech functions. These advances in assistive technology have increased employment opportunities, and the percentage of people who are blind or have low vision in the workforce has increased over the past decade.

Out of sight, out of mind for the sighted

But despite the abundance of assistive technology, people who don’t rely on it are often unaware of how it’s used at work and the challenges users face. My colleagues and I are conducting a five-year longitudinal study to increase knowledge in this area that we hope can help prepare unemployed people who are blind or visually impaired to enter the workforce. The study is to continue until 2025, with the last survey starting in late 2024.

While most of the people we surveyed reported being satisfied with the assistive technology they use at work, almost all reported having challenges with it. The most significant challenges with assistive technology focused on the inaccessible digital environment: documents, software, websites, graphics and photos.

Sometimes digital content is technically accessible but cannot be used by people who use assistive technology. For example, online job application systems often present accessibility and usability challenges. Inaccessible and unusable company software means that those who are blind or visually impaired are often left out of jobs they could easily do because employers’ software doesn’t work with screen readers.

Hiring people who are blind or have low vision has been more difficult than people with other types of disabilities because of the company’s inaccessible software, Ross Barchacky, vice president of business development and strategic partnerships at Go Inclusive, told me. The organization supports companies looking to hire people with disabilities, including matching them with qualified job seekers with disabilities.

Digital accessibility

Although the Americans with Disabilities Act does not specifically mention the digital environment, the Department of Justice has taken the position that Title III of the ADA, which covers public accommodations for people with disabilities, applies to websites and apps. mobile. Thousands of digital accessibility lawsuits are filed under the ADA each year, and the number has increased significantly over the past five years.

Attention is paid to the digital standard setters. The World Wide Web Consortium has developed standards for accessible web content: the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, which have just been revised in version 2.2. The guidelines provide free guidance to help developers make their digital content accessible. Two related standards are Section 508 of the US government and EN 301 549 of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute. World Accessibility Awareness Day was established in 2012 to encourage people to learn and think about digital inclusion for people with disabilities.

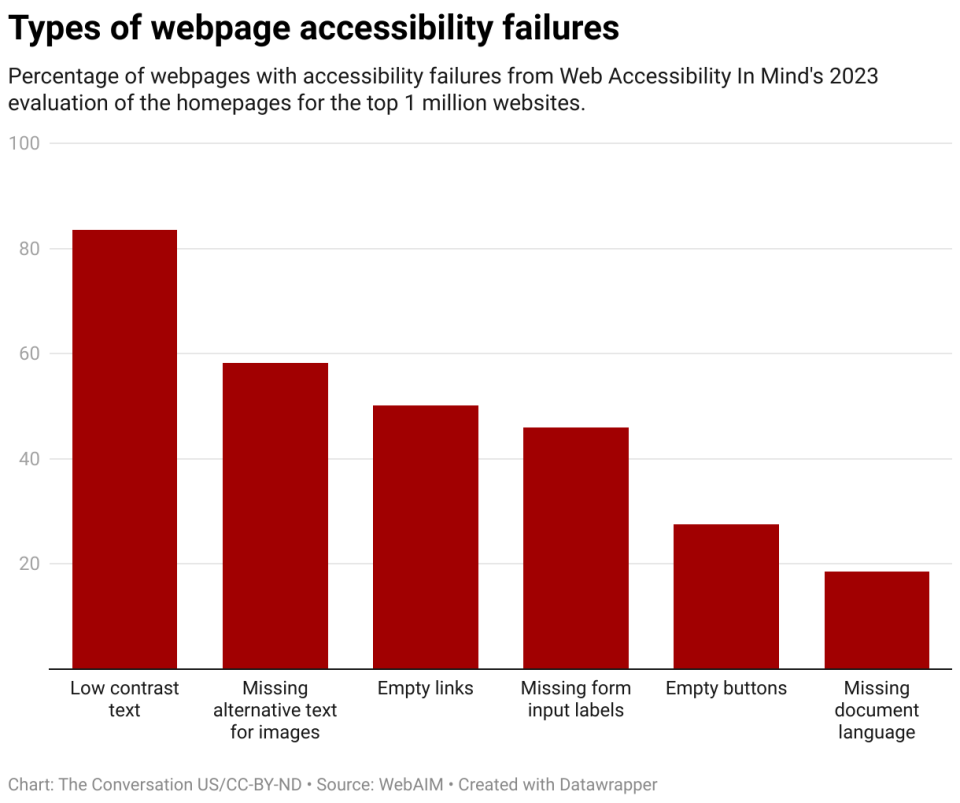

Despite laws requiring and guidelines supporting an accessible digital environment, much if not most digital content is still not fully accessible. In its latest annual review of the accessibility of the top 1 million websites, the non-profit WebAIM found an average of 50 accessibility errors per page. Worse, almost all homepages – 96.3% – failed Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.

What can be done

It’s easier to build in accessibility from the start than to retrofit after the fact.

For accessibility to be built in from the ground up, accessibility would have to be part of the curriculum for digital developers, but it usually isn’t.

Companies could require developers to create accessible software and refuse to buy software that is not accessible. Individuals can help produce their own accessible digital documents – inaccessible digital documents were the most common challenge in the work. Microsoft is working to make producing accessible digital documents easier with its accessibility checker and now its new accessibility assistant.

An accessible digital environment can exist, and as a result there would be more employment opportunities for people who are blind or visually impaired.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Michele McDonall, Mississippi State University

Read more:

Michele McDonall receives funding from the National Institute for Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research. Grant number 90RTEM0007 provided funding for the research discussed in this story.