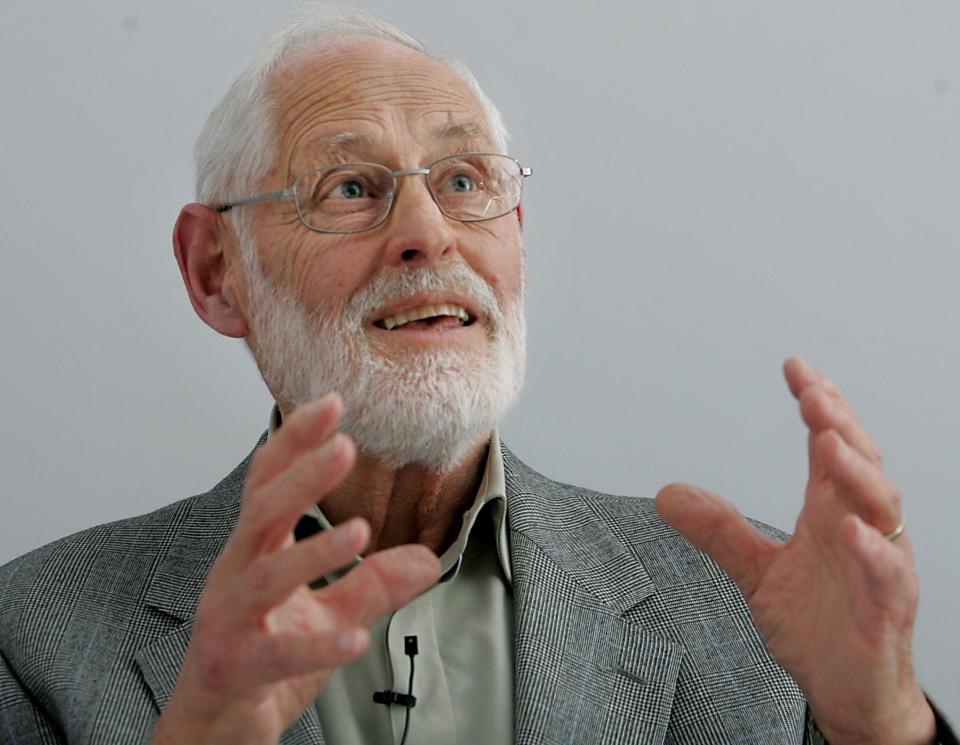

Ivor Browne, who has died aged 94, was a psychiatrist who changed the public’s view of mental illness in Ireland, overseeing the move away from crammed hospital wards and electroconvulsive therapy towards a holistic view of the human mind.

When Browne began his career in the 1960s, mental health provision in Ireland was in a dire state. Irish mental hospitals proportionately had the highest incarceration rate in the world – even higher than the rate in the Soviet Union – and there were, on average, only two psychiatrists per mental hospital (one per 454 inpatients). Often, patients were committed to an institution because they had difficulty with their families or the church. Many of them stayed there for years.

Browne sought to dismantle the system, declaring: “We no longer need the mental hospital as we know it.” While he agreed that some people would always need long-term residential care, he called for hospitals to be integrated into the community, rather than sequestered behind walls. He was against the over-prescription of mood-altering drugs and decided that measures such as electroconvulsive therapy should only be tried when all other forms of treatment had been exhausted.

Instead, Browne argued for talk therapy, which sought to trace mental ill health back to its root. In 1985 his article, “Psychological Trauma, or Unexperienced Experience”, was published in the Irish Journal of Psychiatry. Here, Browne laid out his hypothesis that traumatic events cause the psyche to generate an “abnormal state of consciousness” in an act of self-defense. This causes the body to experience trauma, which Browne called a “frozen site”.

Traumatized children may re-enact the event while playing; adults may have disturbing dreams, flashbacks or severe distress over circumstances that remind them of the past event. “If it was blocked, you’re not reliving the experience,” Browne explained. “You are living for the first time.”

Healing could begin once the patient, with the help of a therapist, had worked through his or her traumatic experience. It was a normal (if unpleasant) memory then; the patient could still recall it, but it was no longer interfering with daily life. In group workshops, Browne encouraged his patients to lie down as they relived their experiences, allowing themselves to respond spontaneously to the trauma.

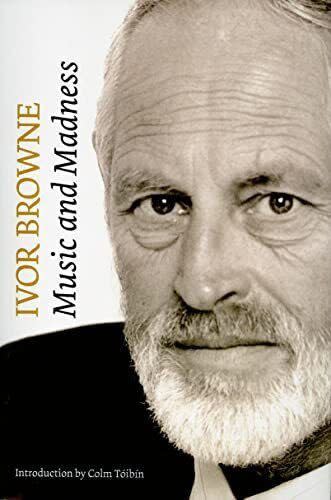

In the introduction to Browne’s 2008 book Music and Madness, writer Colm Tóibín recalled screaming out loud when the “unprecedented” pain of his father’s death finally hit him. Tóibín befriended Browne, and the novelist Sebastian Barry compared Browne to a father figure. “When Sebastian and Ali [Alison Deegan, his wife] We weren’t doing well, we used to bring them fish and chips,” Browne recalled.

Browne was willing to break rules to save lives, and he was known as a gentleman. His sympathy for his patients and their opposition to many established practices of the last century also put him at odds with some colleagues. In 1996 he spoke out on behalf of Phyllis Hamilton, who had children with the renowned Catholic priest Father Michael Cleary. He defended her against accusations that she was a liar and a blackmailer, and went on RTÉ radio to say that Cleary had always been open with him about the relationship.

Therefore, Browne was attacked by the Catholic Church and approved by the Medical Council. He remained unapologetic, however, feeling that he had to prioritize the welfare of his patients over the reputation of the Church. He remained in touch with Phyllis Hamilton and was with her when she died in 2001.

One of five children, William Ivory Browne was born into a middle-class family in Dublin on 18 March 1929. Years later he discovered that his parents, determined not to have any more children, practiced a form of birth control where his mother kept him. bedroom door locked. Ivor was conceived after his father climbed in through the window.

Through his father, an ex-Catholic who defected to the Church of Ireland when he married Browne’s mother, Ivor inherited a love of literature, music and history. His mother nurtured his spiritual side.

As a boy Ivor struggled with dyslexia and did poorly academically, but he loved music and took up the trumpet. After leaving Blackrock College he went on to the Royal College of Surgeons, where he spent much of his time playing jazz. One professor told him: “You can only be a midwife or a psychiatrist.”

In his third year at RCS he contracted tuberculosis, which put an end to his trumpet playing. After graduating in 1955 he started out in neurosurgery where, as a student, he assisted with lobotomies (which he later regretted). He went on to a post at Warneford Hospital in Oxford, before returning to Ireland and St John’s Hospital in Dublin.

It was then that he began to question the use of psychotropic drugs as he watched schizophrenic patients being readmitted to hospital months after a supposed “cure”. “No matter what we were doing, it was clear to me that we weren’t changing the process,” he recalled.

In 1962 he took a job at St Brendan’s Hospital in Dublin, where he was horrified by the overcrowding and the use of crude treatments such as insulin coma therapy. He became a medical superintendent in 1966 and began setting up group therapies in a disused church on hospital grounds. His approach involved new drugs, intensive face-to-face therapy, and transitioning patients back into the wider community.

At the same time he was experimenting with more radical and controversial therapies, such as the use of LSD and (later) ketamine. He had a lifelong interest in Indian spiritual practices and promoted the psychological benefits of yoga and meditation. He presented a manifesto for change in his interview for the position of chief psychiatrist of the Eastern Health Board, and was appointed to the post in 1966, eventually resigning in 1994.

Ivor Browne was Professor of Psychiatry and Head of Department at University College Dublin from 1967. He was also president of the Committee of Experts on psychiatric reform in Greece and was a director of the Irish Foundation for Human Development.

Browne was tall and striking, with a white beard, and would often hug people. He was very popular on the jazz scene and founded the record label Claddagh Records with his friend Garech Browne, heir to Guinness. Unafraid to die, he believed in reincarnation and once said he felt he might have been an Italian monk in the past.

With his first wife, Orla, Ivor Browne had four children. The marriage ended in divorce and in 1999 he married his partner of 30 years, June “Juno” Levine. She died in 2008.

Ivor Browne, born 18 March 1929, died 24 January 2024