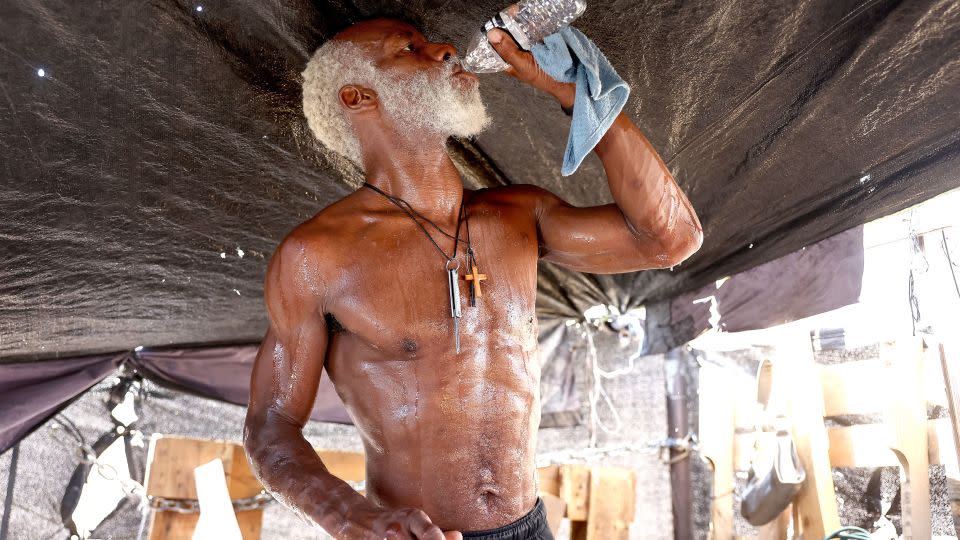

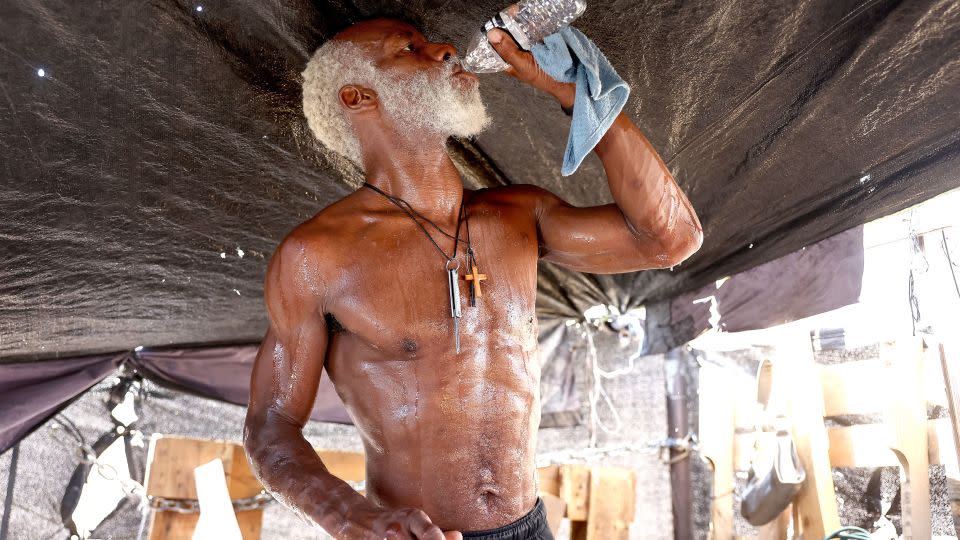

When Hurricane Ida hit Louisiana with catastrophic flooding and powerful winds in August 2021, more than a million people lost power. Then came the heat wave. Temperatures rose above 90 degrees Fahrenheit – a sucker punch for those who are sweltering in their homes, able to put on air conditioning as power outages extend for days.

The heat was the deadliest in New Orleans, responsible for at least nine of the city’s 14 hurricane-related deaths.

The combination of a hurricane, a heat wave and a multi-day power outage is a nightmare scenario, but it’s one set that will become more common as humans continue to heat the planet, leading to more extreme weather. And it reveals an uncomfortable truth about the fragility of humanity’s ultimate defense against heat: Air Conditioning.

Air conditioning is far from perfect. It reduces energy, most of which still comes from fossil fuels to heat the planet, which means it increases the problem it is used to alleviate. Furthermore, it is only available to those who can afford it, which increases social inequality.

But it is also a lifesaver against increasingly brutal heat, the most stagnant kind of weather. It allows people to live in places where temperatures are pushing close to the limits of viability and where extreme heat persists even at night.

Demand for AC is increasing, and is expected to triple worldwide by 2050, as global temperatures rise and incomes increase.

The problem is that without electricity, access to air conditioning is lost. And many electrical grids are being pushed to breaking point by increasingly frequent extreme weather and growing demand for cooling.

Weather accounted for 80% of major power outages across the US between 2000 and 2023, according to a report by Climate Central, a nonprofit research group. “All aspects of the weather are affecting the already fragile grid and really putting it to the test,” said Jen Brady, senior data analyst at Climate Central.

In the United States, the aging grid was designed “for the past, not the future,” said Michael Webber, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Texas at Austin.

The main threat is storms, which can bring down transmission wires and poles. But heat also has an effect. If it is really hot, the system works less efficiently. Webber compares it to how someone would feel running a marathon in the heat – “we just break down.” The grid can also buckle under the weight of demand because everyone is turning up their AC at the same time to deal with high temperatures.

The number of major outages in the United States — those affecting more than 50,000 customers and lasting at least an hour — doubled between 2017 and 2020, said Brian Stone Jr., a professor specializing in planning and urban environmental design at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “Most of the increase is happening during the summer months, which tells me that these systems are not resilient,” he told CNN.

Surging demand for cooling during an August 2020 heat wave in California prompted the state’s main grid operator to cut power to hundreds of thousands of homes in rolling blackouts for the first time in 20 years.

In 2021, during the blistering heat wave that scorched the Pacific Northwest, power equipment buckled in the heat, which triggered rolling blackouts for miles and the temperature rising above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

It is not just the US that is struggling. In June, when temperatures in southern Europe exceeded 104 degrees Fahrenheit, parts of Albania, Bosnia, Croatia and Montenegro were affected by darkness at times as demand for electricity increased.

Even short power outages can be dangerous. “If the grid goes out and there’s a heat wave, it goes from uncomfortable to deadly pretty quickly,” Webber said.

Heat can affect vital organs and cause heat exhaustion, heat stroke and even death. If the power goes out when it’s very cold, people can add layers, make fires and huddle together. “If it gets really hot, there’s only one way to cool it, and that’s with electricity,” Webber said.

The combination of a heat wave and power outages is “the deadliest climate event we can imagine,” Stone said.

He and a team of scientists explored the potential impacts of a heat wave at the same time as a multi-day outage caused by extreme weather or cyber attacks. Focusing on Atlanta, Detroit and Phoenix, they looked at exposure inside people’s homes, a major driver of heat-related illnesses during power outages.

The figures were extremely stark for Phoenix. During a heat event with a three- to four-day outage, half of the city’s population — nearly 800,000 people — would need hospital treatment for heat-related illnesses, according to the findings. There would be over 13,000 deaths.

Power outages in Phoenix caused “a very dramatic change in heat illness,” Stone said, because the city’s climate is so extreme that people struggle to acclimatize. Unfortunately, widespread air conditioning could make residents less resilient because they are so used to cooling in their homes and workplaces, Stone said.

Phoenix authorities say the city is well prepared. Kate Gallego, the city’s mayor, said Stone’s research was based on a very unlikely scenario. “The study doesn’t account for any of the emergency response plans that are in place, or the fact that our electric grid is consistently among the most reliable in the country,” Gallego told CNN.

Arizona Public Service, one of the energy companies that provides power in Phoenix, said it has robust plans in place to prevent large-scale outages and regularly maintains the grid.

But while the odds of a combined multi-day power outage and heat wave in Phoenix may be low, Stone said, it’s still possible and will become more likely as the climate crisis worsens.

Significantly cutting planet-warming pollution is the best long-term defense against extreme heat and weather, but the world is already committed to decades of rising temperatures, Stone said.

In the short term, there are ways to limit vulnerabilities.

One that Stone said is to make the grid stronger and more resilient. This includes repairs and upgrades that take the future climate into account. Expanding and modernizing the grid, including adding more power plants and ensuring a diverse range of energy sources, will also help strengthen it, Webber said.

“But we also have to acknowledge that those grids will fail, and they’re failing at a higher rate of frequency, so we have to have backup plans,” Stone said.

That means rethinking cities, where trees have been replaced by heat-trapping concrete, steel and asphalt. Designing urban areas to be greener and cooler “The resilience of the grid can be greatly increased without investing in the grid itself,” he said.

Climate Central’s Brady cited community solar projects, which can keep local power running when the grid goes down. Babcock’s farm in Florida – “America’s first solar-powered town” – managed to keep the lights on in 2022 when Hurricane Ian passed through, unlike nearby towns.

It will also help make homes more efficient, Webber said. Homes that are better adapted to extreme weather can help reduce demand for electricity when temperatures rise.

Ultimately, “we are vulnerable because our lives are built around conditioned air,” Webber said, living in places where life would be impossible without it. The stress that extreme weather is putting on the grid shows that “climate change is here and we have to deal with it.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com