Beautiful, terrifying and unfathomably vast, the world’s oceans are some of the least understood places on earth. To put it mildly, there are things below that we don’t know about – and because it’s a fundamentally inhospitable place, exploration has been treacherous and slow. But Sean Wolpert, president of Deep, doesn’t just want to speed up our discovery of the oceans – he wants people to live there too.

“What I’m most excited about is finding something that will improve people’s quality of life in the long run,” says Wolpert, who says there may be missing keys to land problems lurking beneath the waves .

“It’s very likely that we’ll find the cure for something like cancer in our oceans.

“If you think about sea sponges, for example, they eliminate organisms trying to eat them through chemical processes to ensure continuity and survival. So what can we learn from that process in terms of our own biological makeup?

“Pharmacy is a very exploratory subject,” he says.

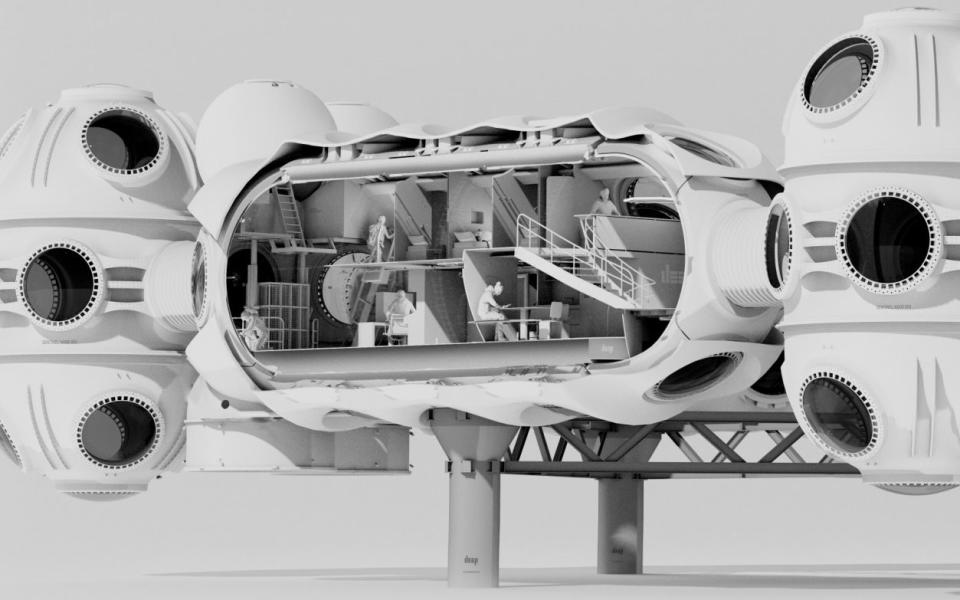

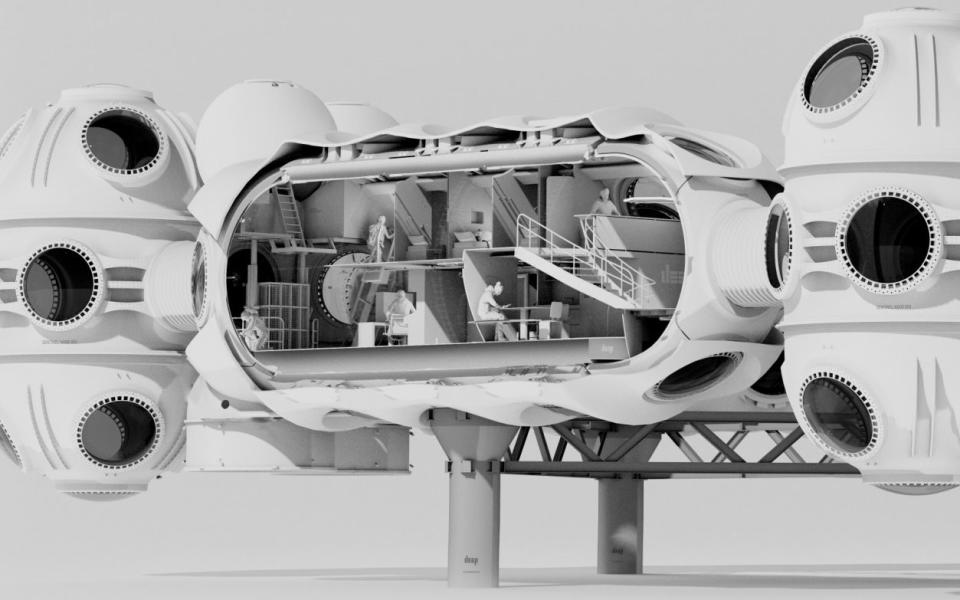

Deep – an ocean technology and exploration firm, funded by private investors – launched stealthily in 2021, but now has 100 staff across the UK, US and Canada. They are working on an underwater living space called “Sentinel” which the company says will enable humans to live 656 feet below the waves.

A wooden prototype already exists. The fully functional product, which will be partly 3D printed, is expected to be tested in a flooded quarry in Gloucestershire before being launched in the real world, possibly in the Mediterranean, in 2027. Measuring 57 feet long, with an internal volume of 14,000 cubic feet and powered by renewable energy, the substation will house six people, who can survive underwater for 28 days.

“It will open a new wave of ocean exploration,” says product director Rick Goddard.

“Researchers could be studying the behavioral cycles of tuna, or examining coral bleaching. They could be researching carbon capture, or investigating an archaeological shipwreck off a Greek island.

“There will also be incidental science, where scientists can sit in one of the hub’s huge windows and observe animal behaviour. We need climate scientists down there. We need massive amounts of data on ocean acidity and temperature, and the core data that tell us what the oceans are like,” says Goddard.

It will be designed to sit anywhere on the ocean’s continental shelf down to 656 feet, the edge of the shale zone, where natural light penetrates.

This area is too deep for most divers, but too shallow to justify the cost of commercial deep-water equipment, so the water band is little studied.

“It’s going to encourage kids to become marine engineers, biologists because it’s going to be very exciting. And what he sees and what he does to humanity will be very powerful,” says Goddard.

Living underwater comes with significant problems, which is why it hasn’t been very successful so far. It is preceded by a handful of very limited experiments, and one successful attempt by French ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau to build an underwater station in the 1960s, although it was only 32 feet deep. The US Navy also built a Sealab habitat in the sixties, but funding was eventually lost to plow into the space race.

The main problems include low temperature, high pressure and corrosion. The change in gases – such as an increase in helium – also breaks electrical equipment and makes it feel cold; the Sentinel habitat needs to be heated to 32 degrees to make it feel like 21. High humidity also means that lots of bacteria can build up, with people at risk of getting skin and ear infections, and the pressure also means people stop the taste buds at work – so Sentinel people will be eating food loaded with spices.

Goddard says: “What we’re trying to achieve is not a single placement on a single site. It’s about getting the right people under the ocean, and opening it up to non-specialists.

“The ultimate aim is to have hundreds of these deployed around the world. This is not a case of scratching a leg. This is what the planet needs, and what our oceans need.”

It must be home to a growing global population, according to Deep, but because the ocean is the planet’s final frontier.

Research by the National Geographic Society shows that more than 80 percent of it has not been mapped or explored – meaning we know less about it than we do about the surface of the moon. It is believed that about 90 percent of ocean species are still missing; so far, we know about 226,000 ocean species but some scientists estimate that there could be several million more.

The distance the Sentinel can reach – 656 feet – is the deepest point at which sunlight penetrates the ocean, and where 90 percent of marine species are found. But climate change, overfishing and ocean acidification are causing unprecedented changes to the oceans, which, according to Deep, need to be understood urgently.

“The jig can go to 200m, but the sweet spot will be 50 or 60 meters down, where it will be lighter,” says Goddard.

At first there will be trained divers who stay in the Sentinel but it is intended Deep soon marine scientists, climate scientists and archaeologists with limited diving training. The participants will go down under pressure through a submarine that will lock on top of the Sentinel. The hub will be pressurized to the same level as the surrounding ocean, meaning that divers can go out for hours, without having to pressurize.

They will do this through a “lunar pool” (a hole that goes into the ocean) and will be connected by cables to the mothership all the time – like spaceways in the world.

They can then bring samples back to the Sentinel and work on them in the on-board laboratory – revolutionizing science as it will mean that materials will not need to be brought back to the surface for study, where they could decompose.

At the end of their stay, the participants will spend varying amounts of time in a decompression chamber before returning to the atmosphere at sea level.

Like space flight, the experience is also psychologically demanding, due to the degree of confinement and isolation from the outside world.

Mari Östin, Deep’s human factors engineer, says: “A lot of our research comes from those on the NASA space station.

“We have to look at sleep because that’s important. They had a problem in the space with the sound of people snoring.”

In fact, there are many parallels to the space. Space travel is now regularly carried out by private companies, such as Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic or Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Wolpert says: “There is a wonderful world out there that needs to be explored, and we are private individuals with that ambition.

“We don’t mind being compared to Musk – it could be argued that his Tesla and SpaceX projects are helping the planet.”

Deep has so far spent undisclosed millions on the project, but he believes his project will be affordable for scientists, companies and researchers – especially once hundreds of substations are rolled out.

“The cost will be like a time share. It will be more cost effective for universities or companies to hire a substation for weeks at a time,” says Wolpert.

And will it be exploited?

“That’s always a possibility. We are people after all,” he says. “But the main risk people might think about is deep-sea mining, and we’re not prepared to do that. This is non-extractive. We are here to leave the ocean a better, better understood place.”

Goddard adds: “At the moment, the people who are going down there, especially oil and gas, are those people on their minds.

“So what we’re doing is putting other people with eyes down there. It’s called Sentinel for a reason. That is its purpose – to be the watchtower.”

It is clear to the company, however, that the strongest phases of the project in the future are quite as exciting as the coming years.

Mike Shackleford, Chief Executive Officer, says: “Let’s be clear – this was science fiction, but we’ve done away with the fiction. The ocean is being destroyed. Acts of ocean terrorism are committed by many countries.

“We have to be down there, researching the area and in the process, making people watery. This is the start of a 300-year project.”