From an iPad on the kitchen table, a digital voice reads out a story to Dipti Bhide and her son, Rohan.

It’s about an astronaut who went to Mars, met an alien and found some space rocks before coming back to Earth. The pair, who live in Coquitlam, BC, are the first people to ever hear the story, which was created using suggestions from Rohan, who were then fed into the artificial intelligence (AI) program created by his mother.

Eight-year-old Rohan is completely engrossed in the story.

“It’s a story he created so he’s very motivated,” said his mother.

Bhide is not the first developer to imagine the potential of advanced computing automation for children’s learning. Her program is one of many new AI offerings, like Funexpected Math or Ello, available for purchase online that promise to engage young children in the seemingly limitless nature of technology.

But while the programs claim to improve a child’s understanding of the basics, education researchers say the huge potential comes with emerging concerns about privacy, transparency and potentially damaging biases, especially given young age of potential users.

Some of these concerns were reflected in a recent report by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and standards developer CSA Group, which found that policy makers have failed to recognize children’s privacy rights, specific needs, as well as unique circumstances. children. ,” and most of the policy responses left “largely adult-centered.”

Despite the unknown, apps for people of all ages continue to launch, as developers ride the wave of interest in AI, sprouting technology that aims to do everything from improve medical diagnosis to help the elderly with art to do.

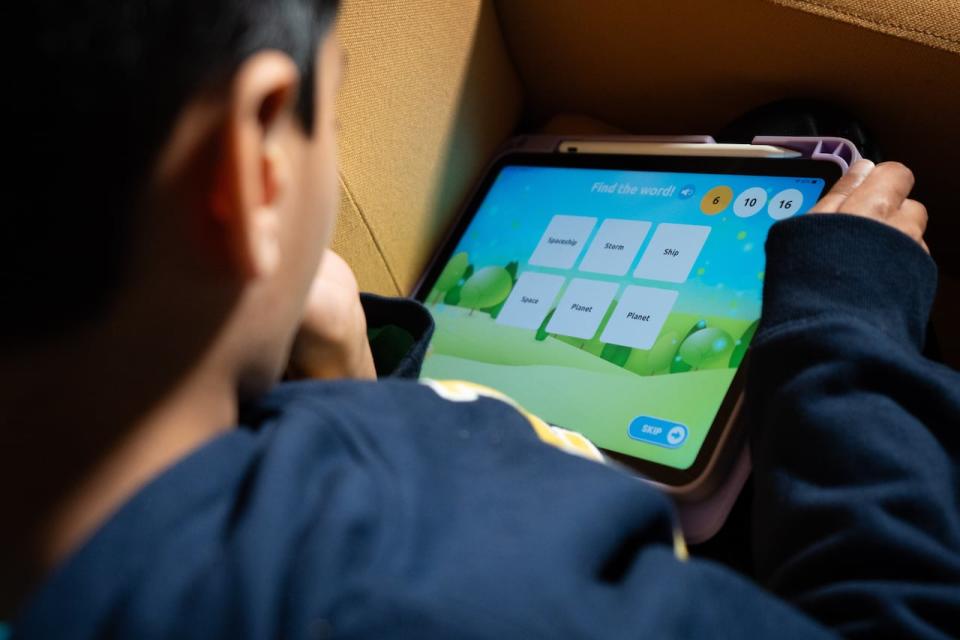

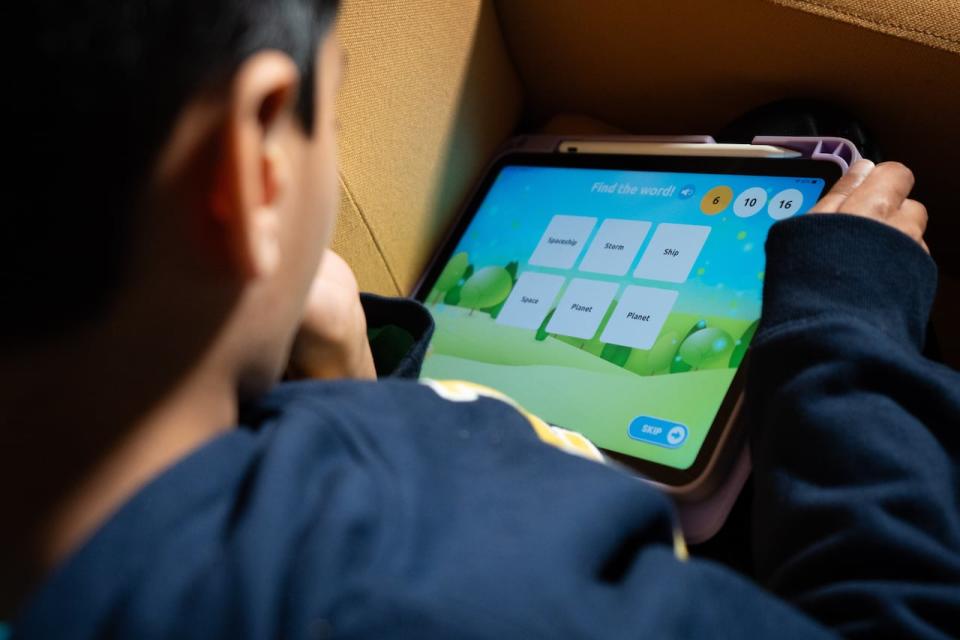

Eight-year-old Rohan plays a LittleLit game on a tablet in Coquitlam, BC (Maggie MacPherson/CBC)

Bhide tells CBC that she wants to make sure her children are ready for the inevitable rise of artificial intelligence in their future and her LittleLit program is a “co-pilot” in their education.

“There’s AI now. What skills do you need to teach your child to keep up with that, and hey, AI can help with that too,” she said.

We are inherently neither good nor bad

Elizabeth Adams, a US-based clinical psychologist and co-founder of the AI-driven program Ello, tells CBC that she worries about developers using the technology without the right educational approach.

Ello uses child speech recognition technology and AI to build an online reading coach for children using an AI avatar in the form of a friendly blue elephant called Ello, who listens and corrects children as they read aloud.

Ron Darvin, an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia who specializes in digital learning and literacy, says artificial technology is ‘not fundamentally good or bad for us’. (Georgie Smyth/CBC)

“The challenge is that there is a rush and there may be products on the market that are not safe or are not the best experiences for children,” said Adams.

“My concern is that if some of that goes away, parents will be raising their guardrails even more.”

With an emphasis on built-in features, such as allowing users to opt out of sharing different types of data, developers like Bhide and Adams hope to reassure parents and ask them to consider tools artificial technology for their children.

That’s not to say, however, that AI is inherently bad or good for adults or children, said Ron Darvin, an assistant professor at UBC who specializes in digital learning and literacy.

“We can really understand what the benefits and limitations of these tools are and shape them in a way that empowers us as humans.”

He told CBC the real issue is digital literacy — not just knowing how to use artificial intelligence technology but understanding how it works and the principles behind it.

No replacement for personal learning

Rohan plays a LittleLit game on a tablet. (Maggie MacPherson/CBC)

If children are receiving responses to certain verbally delivered cues, programs may be recording voices, Darvin said. AI technology could also be able to read facial expressions. Sometimes programs also collect additional data while using the program, an essential part of machine learning, which can be stored locally or shared with third parties.

The apps can’t replace the value of personal learning, Darvin said, because they’re essentially limited to the instructions built into the software, often called algorithms.

In the case of LittleLit, it means that the software can be programmed to offer age-specific content. But it can also leave out alternative data, which could lead to AI programs feeding repetitive, formulaic content or perhaps not being able to recognize a person’s unique accent or facial expressions, he said he.

Even AI’s amazing ability to make math or reading problems instantly out of unicorns or chocolate bars can’t compete with the value of face-to-face learning, according to Dipti Bhide, co-founder of LittleLit. The developer, who hopes one day the program will be used in schools, is convinced that there is no substitute for a teacher or parent despite the potential of AI.

It’s a view shared by Christine Korol, a psychologist at BC Children’s Hospital, who said there are years of research showing that parent-child book interactions are some of the best ways to encourage children to explore their interests and -motivation to improve reading.

“You spend quality time with each other, you laugh about stories,” she said. “There are many things that parents bring to the table when they read with their children.”