Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What is dirt? – Belle and Ryatt, ages 7 and 5, Keystone, South Dakota

When you think of dirt, you might picture the rock dust that gets on your pants. But there is much more going on in the ground beneath our feet.

When I started studying the soil, I was surprised how much of it is actually alive. The soil is teeming with life, and not just the earthworms you see on rainy days.

Keeping this vibrant world healthy is essential for food, forests and flowers to grow and for the animals that live on the land to thrive. Here’s a closer look at what’s underneath and how it all works together.

The rocky part of the soils

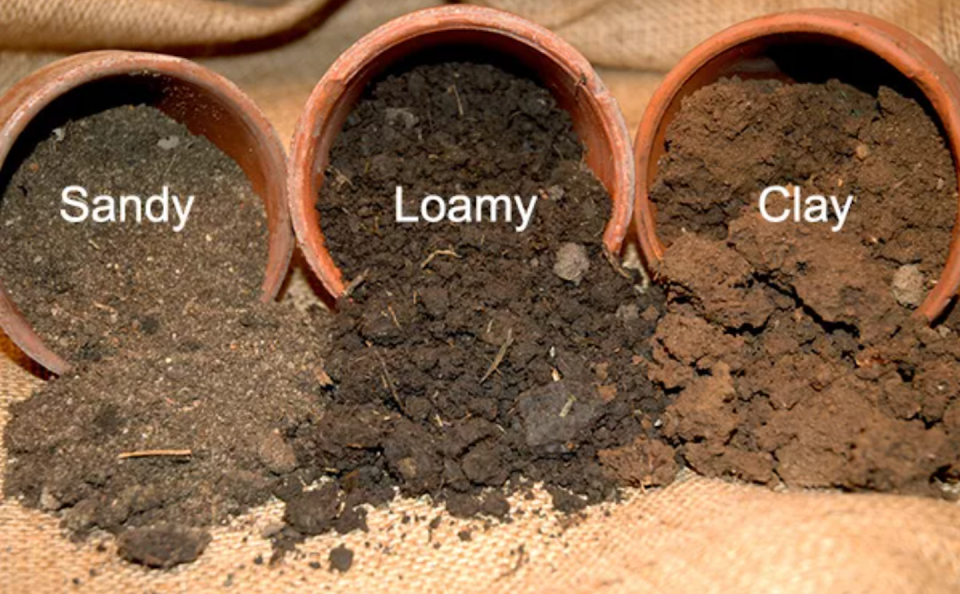

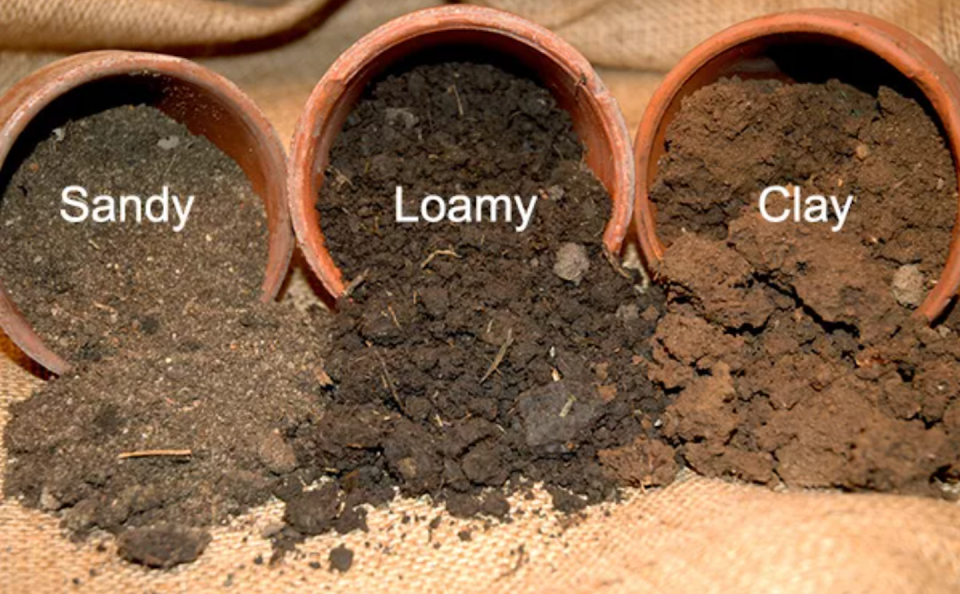

If you scoop up a handful of dry soil, the basic dirt you feel in your hand is very small pieces of weathered rock. These small bits have been eroded from larger rocks over millions of years.

The balance of these particles is important to how well soil can retain water and nutrients that plants need to thrive.

For example, sandy soil has larger rock grains, so it will be loose and can be easily washed away. It will not hold much water. Soil with clay is mostly finer and denser, making it difficult for plants to access its moisture. Between the two amounts is silt, a mixture of rock dust and minerals often found in fertile floodplains.

Some of the most productive soils have a good balance of sand, clay and silt. That combination, along with the remains of dead plants and animals, helps the soil retain water, allows plants to access that water and minimizes erosion from wind or rain.

The wriggling parts, munching the soil

Amongst all those rock particles is a whole world of living things, each one busy doing its job.

To get an idea of how many creatures there are, picture this: There are over 1,000 species of animals at the zoo in Omaha, Nebraska. But if you scooped up a small spoonful of soil in your backyard, there would probably be at least 10,000 species and about a billion living microscopic cells.

Most of these species are still largely a mystery. Scientists don’t know much about them or what they do in the soil. In fact, most species in the soil don’t even have a formal scientific name. But each has some kind of role in the vast soil ecosystem, including generating the nutrients plants need to grow.

Imagine a leaf falling from a tree in late autumn.

Inside that leaf are many nutrients that plants need, such as nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus. That leaf also contains a lot of carbon, which stores energy that can be used by other organisms like bacteria and fungi.

The leaf itself is too large for a plant to take up through its roots, of course. But that leaf can be broken down into smaller and smaller pieces. This process of breaking down plant and animal tissue is called decomposition.

When the leaf first falls to the ground, arthropods – such as insects, mites and collembolans – break the leaf down into smaller chunks by shredding the tissue. Then, an earthworm might come along and eat one of the smaller chunks and break it down even more in its digestive tract.

Now the broken leaf is small enough for microbes to enter. Bacteria and fungi release enzymes into the soil that further break down organic matter into even smaller pieces. If enough microbes are active, this organic matter will eventually be broken down enough so that it can be dissolved in water and taken up by the plants that need it.

To help this process, there are many small animals, such as nematodes and amoebae, which eat bacteria and fungi. There are also predatory nematodes that feed on other nematodes to ensure they don’t become too abundant, so everything stays in balance as much as possible.

It is a very complex food web of interacting species in a delicate balance.

Although some fungi and bacteria can harm plants, there are many species that are considered beneficial. In fact, they may be the key to figuring out how to grow enough crops to feed everyone without degrading and overburdening the soil.

Determining your soil type

Scientists have named over 20,000 different types of unique soils. If you’re curious about the soil and dirt in your area, the University of California, Davis has a website where you can learn more about local soils and their chemical and physical characteristics.

Caring for the soil takes work to promote the benefits of its living creatures and minimize their harm, but it is necessary to keep the land healthy and to grow food for the future.

Hello, strange children! Have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you think too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our best.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Brian Darby, University of North Dakota

Read more:

Brian Darby receives funding from the United States Department of Agriculture.