“Man overboard!” they cried softly as I swung precariously, windmilling my hands in a desperate struggle with gravity, and then sprawled backwards into the sea. “Man overboard!” they shouted again as I spluttered on the surface, in case I was too stunned to hear them the first time. I pulled myself back onto the table, my eyes watering with salt and socks hanging halfway down my back. It was not very dignified. But of course it would be the highlight of their trip.

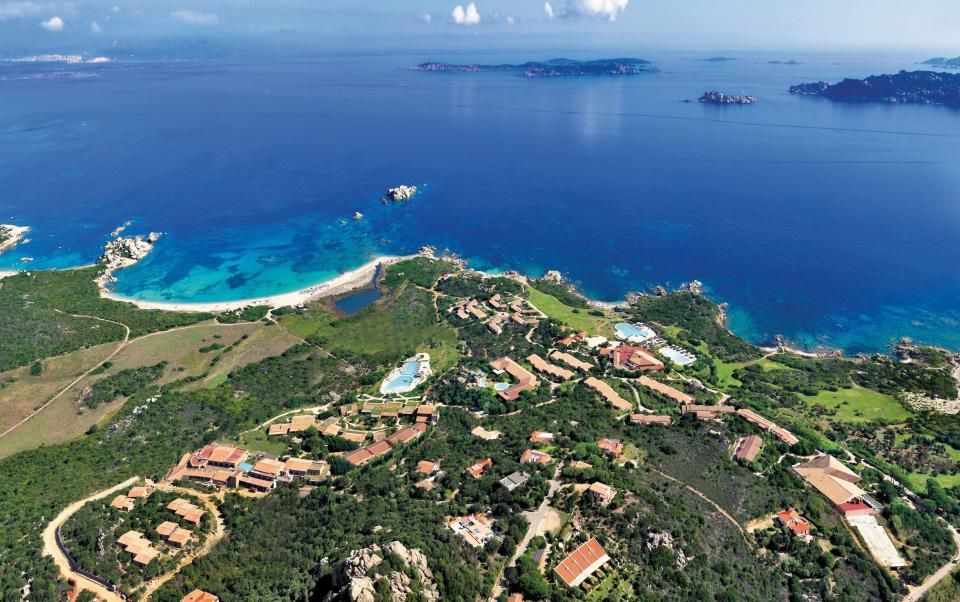

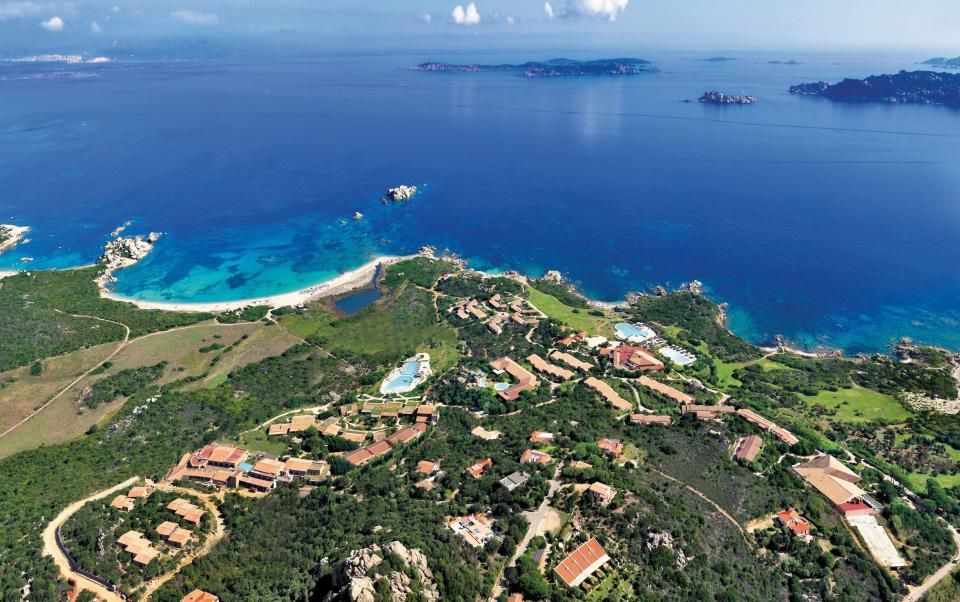

My family and I were in the north-east of Sardinia, an Italian island with rugged wildlife that makes it perfect for outdoor breaks. We were based at the bay of Porto Pollo, an excellent water sports center where windsurfers and aviators jump high, swaying with winds that rush through the channel between Sardinia and Corsica. Porto Pollo caters to both novices and experts, with the four of us – very much in the novice category – spending the morning in the hands of instructor Jonny.

Monika and our six-year-old twins, Matty and Kitty, were strapped into life jackets and settled into a kayak as wide as a whale’s back. I was positioned on a paddle board the width of a strip of dental floss.

Or so it felt to me. Jonny had assured me that this was a very stable beginner’s board, so it was really hard to drop. I want to take it immediately that Jonny doesn’t like it. He had bright eyes and a designer mustache, accented by ringlets of hair that cascaded over his shoulders. Here, I had declared it to my wife and her gaze lingered on him across the sand, which was a stereotypical surfer dude who thought more about shampoo than anything substantial.

“Do you see that rock in the distance?” Jonny asked in his deep voice, scrambling towards a boulder jutting from a headland across the bay. “We will go there.” And so we set sail from the beach, Jonny leading the way on his paddleboard as he lazily pulled on the oar, the rest of us paddling wildly behind like a gaggle of errant ducklings.

At first, the water was flat, and I was pleasantly surprised by my progress. I kept my maiden strokes close to the board, just like Jonny had shown me, and remembered to change my hand positions as I switched from one side to the other. But as we moved further from the shore, the sea became rougher and my progress more difficult.

And then the “man overboard” started. One man overboard. Two men overboard. Three and four. A motorboat passed a hundred meters away and I waited patiently for the wash to reach me and the inevitable man overboard number five.

Ahead, Jonny continued with ease, dropping to his knees from time to time to tackle bumper hats, before nimbly returning to his feet, upright and still like the real head of the ship. His tanned, muscular back looked carved from polished wood. I straightened my back, trying to forget that it probably looked more like margarine than mahogany, but the effort backfired and I collapsed again.

In addition, Monika kept the kayak on course with little effort, the twins rowing merrily with sticks they found on the beach. As the boulder grew closer, the wind brought the scent of pine trees and the hum of cicadas, and with a desperate effort to escape the current’s conveyor belt, we rounded the headland and entered a hidden cove.

Everything was calm here. We hauled boards and kayaked up a thin crescent of sand, and the children immediately got down to business hunting for treasure among the rock pools on the edges. The clear water in the hollow was entwined with dancing lines of sunlight, and from it rose several fine sandstone boulders, bone-colored and bored with hollows like eye sockets.

All the cliffs climbed around us, wagons circled against the open sea beyond. You could almost forget there was such a thing as the open sea. No wind, no crashing waves, no people in speedboats. Suddenly, in a way, I knew I’d misread Jonny. This place was the real Jonny.

“Bat!” exclaimed Kitty as a large butterfly flitted past, and Jonny laughed. “I love kids,” he said. “The lockdown was terrible for them – like trees growing inside.” As we rested with the sun warming our backs, I actually spoke to Jonny, and he told me about life on his family’s small farm in southern Italy, appreciating the layers of judgment that surrounded him. . “I spend some months teaching water sports, but most of the year, I work on the farm. We have 4,000 olive trees, and our friends help make the olive oil. It’s a nice, quiet life.”

It was time to go; Jonny had a kite lesson to teach. It took several minutes to clear the pole, bagging up some weather-beaten pieces of plastic that had washed up on the beach, and then we started paddling back. I was now steadier on my feet and had learned to expect patches of turbulence. I would come a long way.

We returned to the sea many times in the following days. The children had a windsurfing lesson on pint boards with the ever-patient Anya, who took them for a joyous spin on her own expert board, jumping across the seashore while clinging to her feet.

We organized a snorkelling trip from the port of Santa Teresa Gallura, crashing across the zodiacal waves before dropping anchor near Punta Contessa, which Chiara, our guide, described as “a mountain under the sea”. I followed her into its dark caves and crevices, searching for moray eels, while the children paddled around the boat, watching the fish dart among the sedges of a white sea plant called virgin wine glass marine

The call of the land is also strong in Sardinia, and scores deep with tradition and history. The hilltop village of Aggius has for centuries been a center for weavers, and amongst its dark lanes we found Gabriella Lutzu in her workshop, pushing and pulling colorful woolen threads through a wooden loom. She was weaving a rug by hand, taking it up line by line. “It takes Gabriella a whole day to make that little strip,” I told Kitty. She considered this for a moment. “So Gabriella doesn’t have lunch or dinner?”

Most impressive of all are the many archaeological sites scattered among sun-drenched vineyards, Bronze Age forts with towers to climb and secret passageways to discover, and ceremonial stones with ancient hand-carved patterns that can still be traced with today’s mayor. . “Think how old this is,” I pointed out, as we peered through the arched entrance to an ancient burial chamber in Arzachena known as the Tomb of the Giants. “Is he older than you, Daddy?” Matty wondered. “Yes, he is older than me! It’s been here for 3,000 years!” “Older than Grandma?” he asked. “Of course not older than Grandma,” I assured him, because everyone knows that Grandma is as old as the sea itself.

Fundamentals

Planet Travel Holidays (planettravelonline.com, 01273 921001) is an ATOL award-winning specialist in luxury ocean sports holidays, offering tailor-made tours to Sardinia. A week’s package is available from £1,400-2,000pp (including accommodation a short drive from the water sports center in Porto Pollo) and beginner’s instruction (including equipment hire) in boarding, windsurfing, kitesurfing or diving scuba. excluding flights).

Bronze Age Sardinia

Bronze Age archeology can be found throughout Sardinia, and there are said to be up to 7,000 sites in total. These constructions – dating back to around 1500 BC. – involved the work of the Nuragic People, a civilization that thrived for 1,000 years until the Carthaginians and Romans took over. The island sat on various trade routes, and the Nuragic people seem to have prospered by selling valuable raw materials such as copper and lead.

The prosperity of these ancient islanders is reflected in the sophistication of not only some of the decorative and religious pieces they left behind (including bronze statues) but the buildings they lived in and the places where they buried their dead. The most intriguing are so called shower, which is unique to Sardinia. These round towers (like stocky stone beehives) were located in the heart of the villages, and their functions are uncertain: they may have been the residence of the village leaders, fortified defenses, temples or spaces used for meetings.

Nuraghe La Prisgiona in Arzachena – 15 miles south of Porto Pollo – offers a well-preserved example, which new it reaches 6m in height and contains various steps and rooms. It is flanked by a pair of smaller side towers, and beyond are the walls of nearly 100 village buildings. These include huts grouped in small clusters linked by paved passageways, which may have been used by various artisans to make goods that were sold outside the village itself. There is also a well at the base of which archaeologists found a decorated jug buried as part of some kind of ritual ceremony.

Nuraghe La Prisgiona is one of seven sites – including the nearby Tomb of the Giants, a stone passage covered in the shape of a croup where the villagers were buried – that form part of the Arzachena Archaeological Park (admission for single site €7 [£6]combined ticket €25 [£21]children under 12 free).