Urban agriculture is expected to be an important aspect of 21st century sustainability and can bring many benefits to communities and cities, including providing fresh produce to neighborhoods with few other options.

Among these benefits, growing food in backyards, community gardens or urban farms can reduce the distance fruit and vegetables have to travel between producers and consumers – the so-called “food mile” problem. With the end of greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, it is a small step to accept that urban agriculture is a simple climate solution.

But is urban agriculture as climate-friendly as many people think?

Our team of researchers partnered with individual gardeners, community garden volunteers and urban farm managers at 73 sites across five countries in North America and Europe to test this assumption.

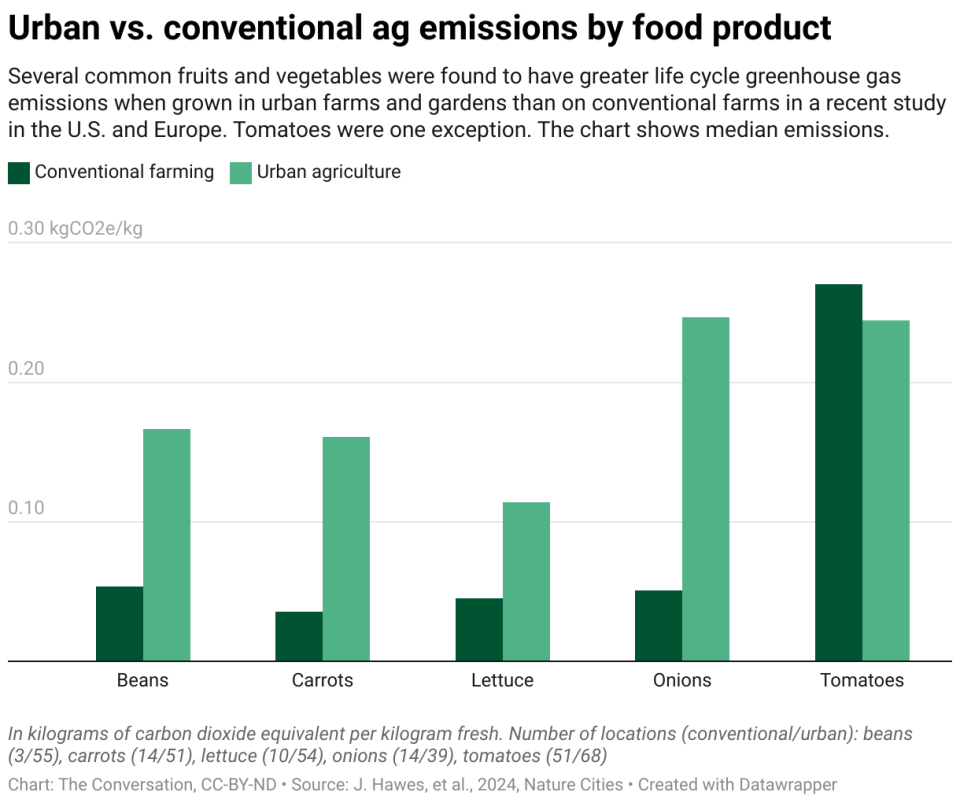

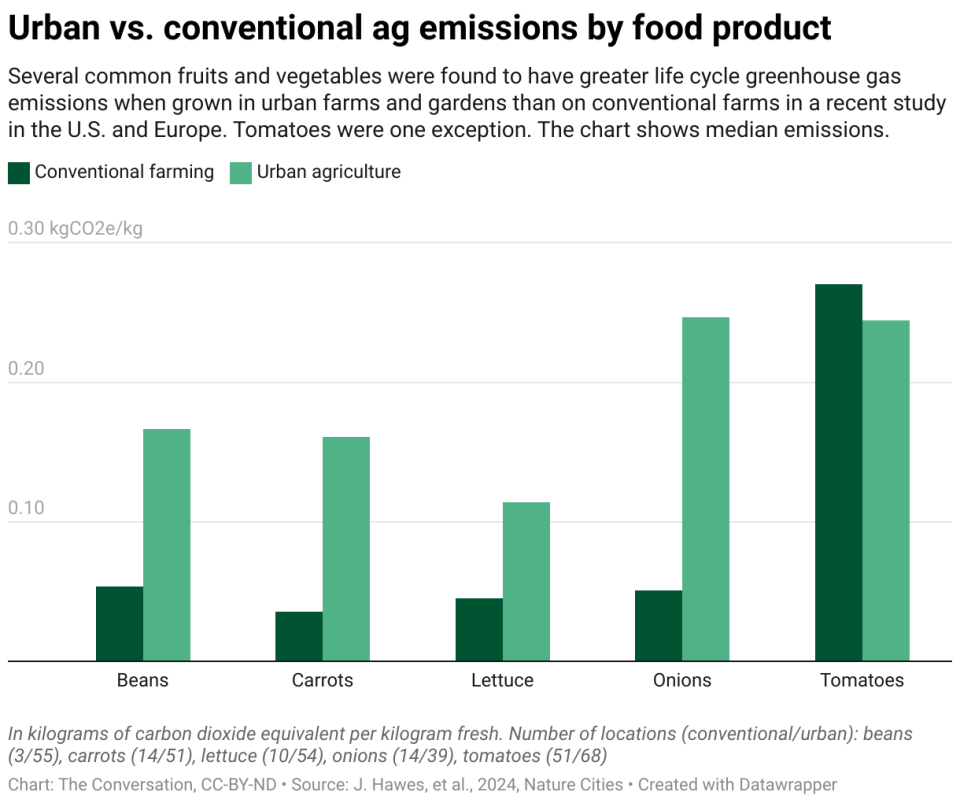

We found that urban agriculture, while having many community benefits, is not always better for the climate than traditional agriculture over the life cycle, even when transportation is taken into account. In fact, on average, the urban agricultural sites we studied were six times more carbon intensive per serving of fruit or vegetable than conventional farming.

However, we also found some practices that stood out in terms of how effectively they can make city-grown fruit and vegetables more climate-friendly.

What makes urban more carbon intensive?

Most research on urban agriculture has focused on one type of urban farming, often high-tech projects, such as aquatic tanks, rooftop greenhouses or vertical farms. Electricity consumption often means that the food grown in these high-tech environments has a large carbon footprint.

Instead, we looked at the life-cycle emissions of more common high-tech urban agriculture – the kind found in urban backyards, vacant lots and urban farms.

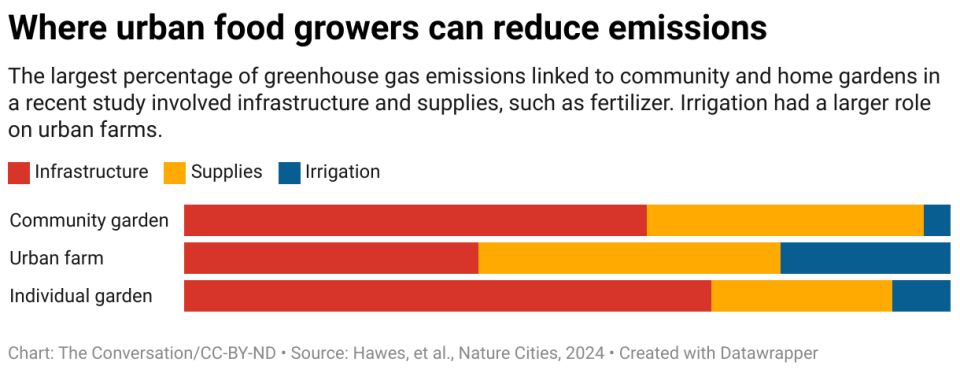

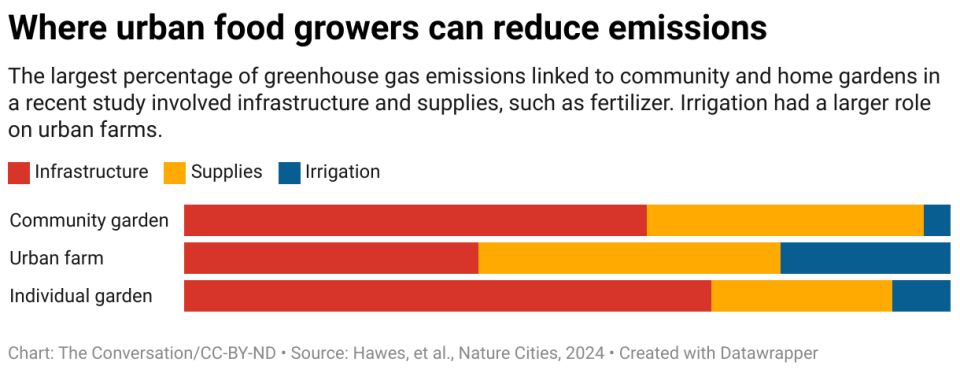

Our study, published January 22, 2024, modeled carbon emissions from farming activities such as irrigating and fertilizing crops and from building and maintaining farms. Surprisingly, in terms of lifetime emissions, infrastructure was the most common source at these sites. From raised beds to sheds and concrete paths, this gardening infrastructure means more carbon emissions per serving of produce than the typical wide open fields on conventional farms.

However, among the 73 sites in cities including New York, London and Paris, 17 had lower emissions than conventional farms. By exploring what set these sites apart, we identified some best practices for reducing the carbon footprint of urban food production.

1) Use recycled materials, including food and water waste

Old building materials can be used to build farm infrastructure, such as raised beds, cutting out the climate impact of new lumber, cement and glass, among other materials. We found that upcycling building materials can reduce site emissions by 50% or more.

On average, our sites used compost to replace 95% of synthetic nutrients. Using food waste as compost can reduce methane emissions from landfilled food scraps and avoid the need for synthetic fertilizers made from fossil fuels. We found that careful compost management can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by almost 40%.

Catching rainwater or using greywater from drains or for showers can reduce the need for water pumping, water treatment and water distribution. But we found that very few sites used those techniques for most of their water.

2) Grow crops that are carbon intensive when grown using conventional methods

Tomatoes are a great example of a crop that can reduce emissions when grown with high-tech urban agriculture. Commercially, they are often grown in large-scale greenhouses which can be energy intensive. Another example that has a large carbon footprint is asparagus and other produce that must be transported on a plane because they perish quickly.

By growing these crops instead of buying them in stores, high-tech urban growers can reduce their net carbon impact.

3) Keeping urban gardens going long-term

Cities are constantly changing, and community gardens can be vulnerable to development pressures. But if urban agricultural sites can remain viable for many years, they can avoid the need for new infrastructure and continue to provide other benefits to their communities.

Urban agricultural sites provide ecosystem services and social benefits, such as fresh produce, community building and education. Urban farms also create homes for bees and urban wildlife, while providing some protection from the urban heat island effect.

The practice of growing food in cities is expected to continue to expand in the coming years, and many cities are seeing it as a key tool for climate adaptation and environmental justice.

We believe that urban farmers and gardeners can increase their benefit to nearby people and the planet at large through careful site design and improved land use policy.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jason Hawes, University of Michigan; Benjamin Goldstein, University of Michiganand Joshua Newell, University of Michigan

Read more:

Benjamin Goldstein receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Neither Jason Hawes nor Joshua Newell work for, consult with, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. .