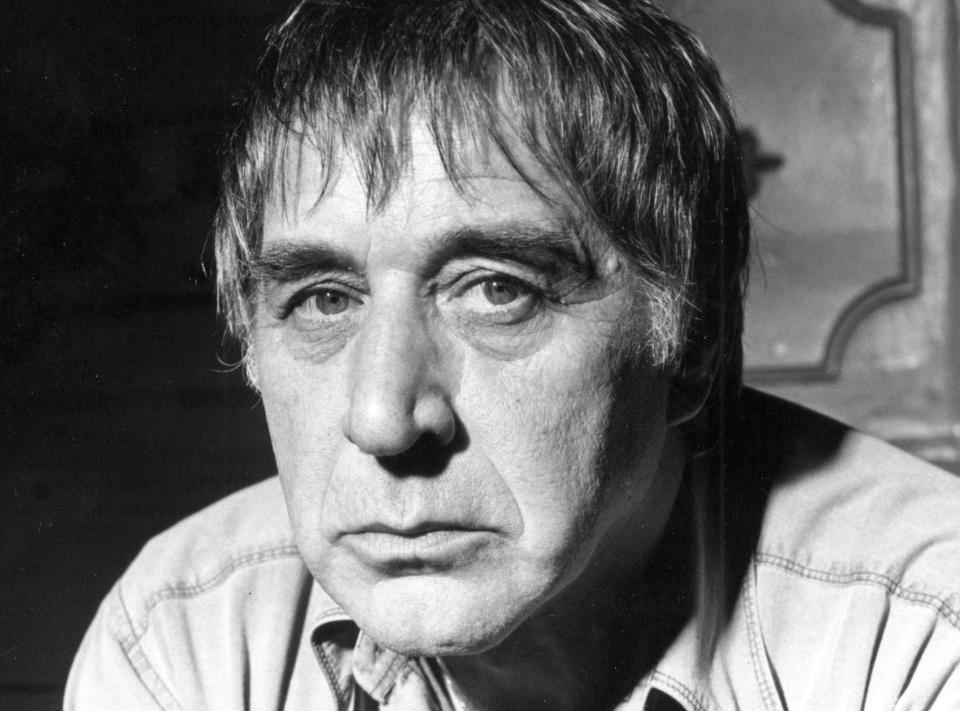

Trevor Griffiths, the stage and television playwright, who has died aged 88, was one of the most original, intelligent and controversial exponents of socialism in post-war British theatre.

A central figure in the debate about how to make left-wing ideals work within a capitalist society, Griffiths was an unrepentant Marxist who was one of the most important writers of class in television drama, his powers of analysis, his linguistic intelligence and the triumph of comic ambiguities. widely respected.

Griffiths had two main graduation achievements. In The Party (1973), left-wing intellectuals and non-intellectuals sympathetic to the student revolutionaries of the 1968 Emergency in France meet to discuss, in a sitting room in Kensington, why British sympathizers did nothing to help them.

The play gave Laurence Olivier his last stage role at the National Theatre. He hoped it would be Shakespearean, but his wife, the actress Joan Plowright, said: “If you do anything as predictable as King Lear, I’ll kill you. Do something modern, for heaven’s sake. Give a demonstration to one of your younger peers.”

Olivier performed a Glaswegian Trotskyite with a 20-minute speech that took four months to learn; but he was drawn to the play because of its lack of political leanings, and nothing came more dryly from the 66-year-old actor’s tongue than when he lashed out at British socialists biting the hand that fed them with care without sticking it.

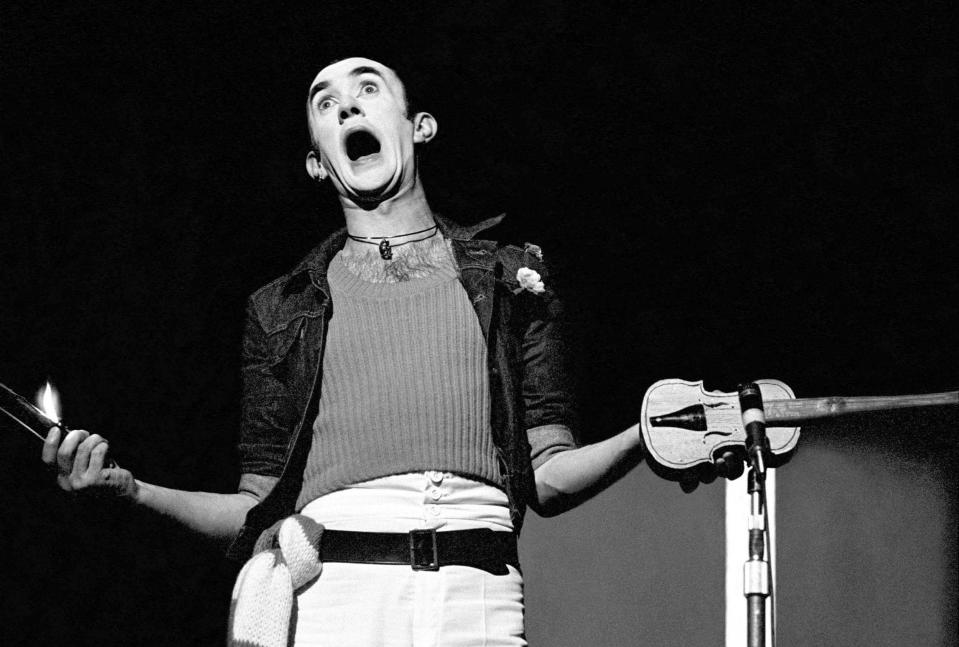

Comedians (1975) had the most praise in general. Masquerading as a comedy about provincial night classes for stand-up comedians, this fierce and funny play was at the heart of a study of revolutionary political activism. Set in a Manchester schoolroom where builders, dockers, milkmen and laborers learn that comedy is deadly serious business, involving anger, pain and truth, it showed ways to engineer laughter out of sex, racial prejudice and physical disabilities.

Its premiere at Nottingham and the Old Vic, when the National Theater was still in existence, resulted in two excellent performances, one from Jonathan Pryce as the most sinister and sinister (and least humorous) of apprentices, the other from a real chance of the. variety hall, Jimmy Jewel, of the former double act Jewel and Warriss.

But Griffiths soon came to the conclusion that he was only addressing the middle classes or the politically converted in the theatre. So he turned to television instead because it “cuts across classes”. Thus began what he called “the strategic penetration of the central communication channel”.

He was commissioned by the BBC to write Such Impossibilities as part of its 1972-73 series The Edwardians, but it was never filmed, apparently on cost grounds but probably because of his Marxist view of the violence in a transport strike in Liverpool in 1911. 1974 Play for Today, All Good Men, about a renegade MP who was retiring, Griffiths played down his political convictions. His best achievement on the small screen was the 1976 13-part socialist soap opera Bill Brand, with his account of the career of a Labor MP questioning the parliamentary route to socialism and the role of the Party of Labor.

He also wrote an episode of the BBC’s epic 1974 series Falls of Eagles, a 13-part drama telling the history of Europe from 1848 to 1914. The episode was set in Griffiths’ Absolute Beginners in 1903 and featured Lenin (played by Patrick Stewart), Trotsky (Michael Kitchen) and the rise of the Bolshevik party.

However, the piece of television that Griffiths described as “without question… I’m best known for” was his Play for Today, Through the Night in 1975, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg and starring Alison Steadman as a young woman. of the incoming working class. hospital for a routine cancer test and wakes up to have their breasts removed. It attracted an audience of around 11 million and sparked a national debate about the treatment of mastectomy patients.

His other television work extended from individual dramas, including Oi for England for Central Television (1982), about youth unemployment in cities, and The Last Place on Earth (also Central, 1985), about Scott the Antarctic and construction of national myths. , book adaptations such as Sons and Lovers (BBC, 1981) and contributions to series including Adam Smith and Dr Finlay’s Casebook.

His major films included Reds (1981), co-written with Warren Beatty, who also directed him and starred as American journalist John Reed, who becomes embroiled in the Russian October Revolution. The film won three Oscars and was nominated for nine others, including Best Picture and Best Screenplay. Griffiths also wrote Fatherland (1987), directed by Ken Loach, about the partition of Germany after the war, in which a son searches for his father who left the German Democratic Republic 30 years earlier.

If Griffiths wrote without any political purpose, at least his writing was highly palatable with a sense of psychological nuance and character. “I have to work with the popular imagination,” he said. “I’m not interested in talking to 38 university graduates in a cellar in Soho. My type of writing is not about ego-massage. It’s about impact and penetration.”

Trevor Griffiths of Welsh and Irish descent was born in Manchester on 4 April 1935, the son of a chemical process worker and a bus conductor. He was one of the first generation of working-class children to benefit from the Education Act 1944, and attended St Bede’s College and the University of Manchester where he read English.

After two years of compulsory National Service in the Army, he became an English and games teacher at a private school in Oldham. He also lectured in liberal studies at Stockport Technical College, was joint editor of Labour’s Northern Voice and was series editor for the Workers’ Northern Publishing Society before joining the BBC at Leeds for seven years as a further education officer in 1965.

After his one-act play, The Wages of Sin, premiered in Manchester in 1969, his first full-length work, Occupations, created enough of a stir on Granada’s small stage for new writers that the Royal Shakespeare Company produced it in 1971 on its experimental basis. in London, The Place, Euston.

Considered by critics to be far more subtle than The Party, Occupations evoked the conflict in 1920s Italy between capital and labour, and between two types of communists, personified by Italian workers’ leader Gramsci (played in the RSC production by Ben Kingsley) , and Kabak (played by Patrick Stewart), a Soviet agent who tried to force a strike by Fiat workers into a full revolution.

After two one-act plays, Apricots and Thermidor (Edinburgh Festival, 1971), there was a collaboration with David Hare, Stephen Poliakoff, Snoo Wilson and others on the play Lay-By (Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, 1971). Sam, Sam (Open Space, 1972) played an autobiographical part about the behavior of two brothers, one loyal to his working-class background, the other rising above it through marriage, wondering which one was happy.

Then came his two major stage hits The Party (Old Vic, 1973) and Comedians (Nottingham Playhouse and Old Vic, 1975; Wyndham’s, 1976; and New York). An all-female version of Comedians was successfully staged in Liverpool in 1987.

Griffiths collaborated with Howard Brenton, Ken Campbell and David Hare on Deeds (Nottingham Playhouse, 1978) and in 1982 he adapted his television play Oi for England for the Royal Court Upstairs.

In 1984 the British Film Institute devoted a season to his television dramas, including another Play for Today, Country (1981), directed by Richard Eyre and starring Edward Fox. Completely on site, he looked at Labour’s landslide victory in 1945 from the perspective of an upper-class family living in a house in Kent.

His later stage plays included Real Dreams (1986), which premiered in the US (with a young Kevin Spacey), about a society of middle-class American students in the late 1960s and their fighting alliance with Puerto Rican workers ; The Gulf Between Us (West Yorkshire Playhouse, 1992), about the conflict in the Middle East; Thatcher’s Children (Bristol Old Vic, 1993); and A New World (Shakespeare’s Globe, 2009), about Thomas Paine, an adaptation of a never-used screenplay originally commissioned by David Attenborough for the BBC.

In 1997 the BBC commissioned him to write Food for Ravens, a TV film starring Brian Cox and Sinéad Cusack, to mark the centenary of the birth of Aneurin Bevan, but the BBC tried to restrict the broadcast – the only film he has ever directed, and his most personal project – to Wales, eventually being broadcast nationally on BBC Two just before midnight. “No trailer, no listing in the Radio Times. No DVD,” he told the Independent. However, he won a Bafta.

Trevor Griffiths married, in 1960, Janice Elaine Stansfield, who died in 1977. They had a son and two daughters.

Trevor Griffiths, born 4 April 1935, died 29 March 2024