“Right now, Silicon Valley is the biggest place in the world for high-tech growth and innovation,” Jeremy Hunt told business leaders last week. “But there’s no reason it has to be so dominant.”

But it wasn’t. Those words belong to David Cameron, in a speech he gave near the Old Street roundabout in November 2010. What Hunt said last week was: “I want the British Alphabet (the parent of Google ) to see, I want to see a British Microsoft … a homegrown company with a trillion dollars [market] cap…. That is an expression of my ambition to make the UK the next Silicon Valley of the world.”

Fourteen years have passed, and the ambition of the ministers has not materialised. He still sees the creation of a British Google as something to be desired: “a yardstick of success”, declared Hunt. And he still thinks we will achieve this ambition.

Now here’s another thing the chancellor didn’t say.

“For the first time in history, humans have landed a craft on a comet. It was British, and it was made in Stevenage. And our Mars Rover is much better than NASA’s, as the world will soon see.”

It wouldn’t be a lie. Mr Hunt could also boast that “we are proud to have six high-tech manufacturing companies in the UK worth over a billion pounds”. And that would be true too.

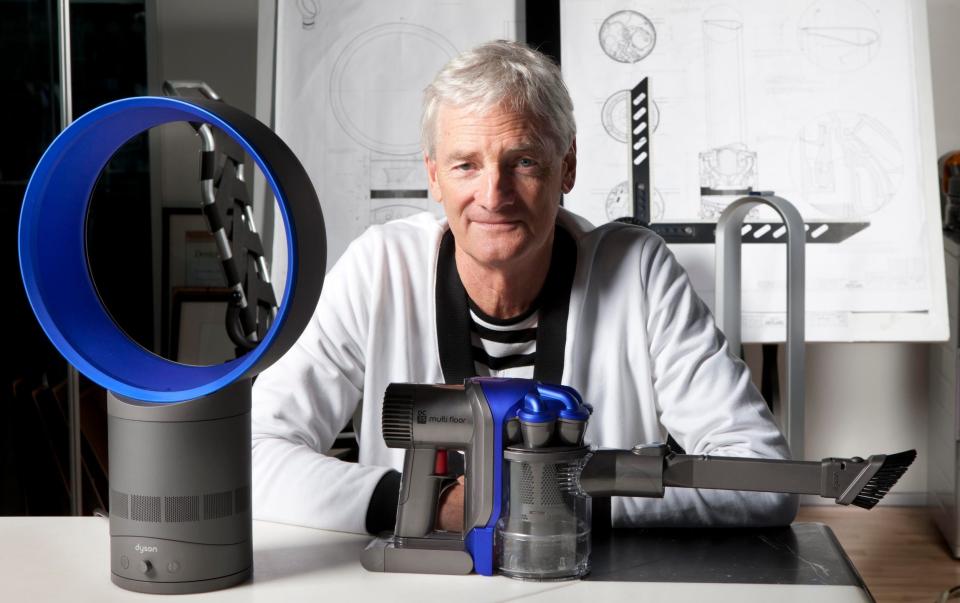

Dyson turned over £7.1bn last year, is respected worldwide, and is currently growing faster than Google. Only slightly faster admittedly, but at 9pc it’s going at a healthy clip.

Renishaw started out specifically to solve a problem with Concorde’s Olympus engines, and has grown into a world-class company: nobody does precise measurements as well. Questor stock tip, the firm is worth over £3bn.

There is no shortage of British tech brains generating wealth at Bamford or Rolls-Royce. Or at Oxford Instruments, whose late founder, Sir Martin Wood, created the amazing superconducting magnets that made MRI scanners possible.

Or at the Airbus space division, once GEC Advanced Electronics, which designed and built the Philae spacecraft that landed on a comet. This is all British technology, and it flourishes even in places we least expect. “Our industrial estates are now the real cathedrals of wealth creation,” I explained recently.

No one disputes that these are all tech companies – what else would you say they do? – solving the most difficult technological problems. But what Silicon Valley has achieved is to redefine and degrade the word “technology” so that it mostly refers to internet companies, much like its own.

Conservative ministers bought this hook, line and sinker. Hunt was hosting a “summit” to talk about the London Stock Exchange by encouraging more firms to list. But by pursuing our ambitions to become the world’s largest digital advertising company, Hunt is belittling what we’ve actually achieved. He is talking about Britain.

We might ask whether a “British Google” is practical or even desirable. The two trillion dollar companies Hunt mentioned are rare animals. Microsoft and Google are once-in-a-generation success stories that have moved themselves into a dominant position in the industry through skill and luck. Microsoft was the biggest beneficiary of the microprocessor revolution, and Google of the internet. These don’t come along very often.

Such ruthlessness was also necessary. In 2000 a judge ordered Microsoft to be broken up, but no one wanted to pick up the pieces, so it stayed intact. Google is facing several major competition trials, leaving it just months away from a similar break-up order.

Last week he offered a check for the full amount of the damages, in case it was lost. He also wants to change the case from a jury trial to a bench trial.

In reality, we don’t have the domestic scale to get our software companies off the ground. “We don’t buy much software in Britain,” one software founder told me last week. He wants governments to make it easier to export software to the big market that matters – the United States. Trade group TechUK echoes this plea.

What tech companies want is simple: a more business-friendly environment. Sometimes the best industrial policy you can have is for the government to get off the business’s throat.

But Hunt confirmed Rishi’s 2021 corporation tax rise from 19pc to 25pc, and scrapped the super deduction. “Corporation tax is now taking a toll on Dyson – it will wipe out any tax credits for research and development,” Sir James himself wrote last year.

And another thing Hunt didn’t say – perhaps understandably – is that the United States doesn’t really like market competition. Two decades ago, British online gambling companies were faster to market, considered much more reliable and did not compete with American rivals. So the US government made online gambling illegal, and arrested our executives when they showed up in US airports.

“The end of all our exploration is to find where we began,” TS Eliot lamented in Little Gidding. For the Conservatives, their curiosity about British technology began and ended in the same place: California.