Since the beginning of the space age — the launch of Sputnik I in 1957 — humans have launched over 15,000 satellites into orbit. Just over half of them are still operating; the rest, having run out of fuel and ended their serviceable lives, have burned up in the atmosphere or are still orbiting the planet as useless metal scraps.

Therefore, they pose a threat to the International Space Station and other satellites, and the European Space Agency estimates that over 640 “breakups, explosions, collisions, or anomalous events leading to fragmentation” have occurred so far.

That created an aura of space junk around the planet, made up of 36,500 objects over 10 centimeters (3.94 inches) and a whopping 130 million fragments up to 1 centimeter (0.39 inches). Cleaning up this debris is expensive and complicated, and there are several plans to do so but no tangible results yet.

One way to tackle the problem is to stop producing more junk – by refueling satellites rather than decommissioning them when they run out of power.

“You can’t refuel a satellite in orbit right now,” says Daniel Faber, CEO of Orbit Fab. But his Colorado-based company wants to change that.

“When satellites run out of fuel, you can’t keep them in the right place in orbit and they become dangerous debris, floating around at very high speeds and risking collisions,” Faber explains. “But also, the lack of fuel creates a whole paradigm where people design their spacecraft missions as small as possible.

“That means we can’t have tow trucks in orbit to get rid of any debris that happens to be left behind. We can’t have repairs and maintenance, we can’t upgrade anything. We can’t inspect anything if it breaks. There are so many things we cannot do and we work in a very restricted way. That’s the solution we’re trying to provide.”

Space surgery

NASA pioneered the concept of refueling and servicing satellites in orbit in 2007, when – in collaboration with DARPA (the research arm of the US Department of Defense) and Boeing – they launched Orbital Express, a mission involving two purpose-built satellites. successfully docked and exchanged fuel. Later, NASA worked on the Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM), which further explored the challenges of refueling existing satellites.

Now the agency is working on OSAM-1, which was due to launch in 2026 and will try to capture and refuel Landsat-7, the Earth observation satellite that has run out of gas.

“This is a mission to refuel a satellite that was unwilling to refuel,” says Faber. “So they have to do surgery on the satellite, cut into it to access the fuel pipes. This allows for an impressive satellite repair capability, but it comes at a price.” NASA said OSAM-1 will cost about $2 billion in total.

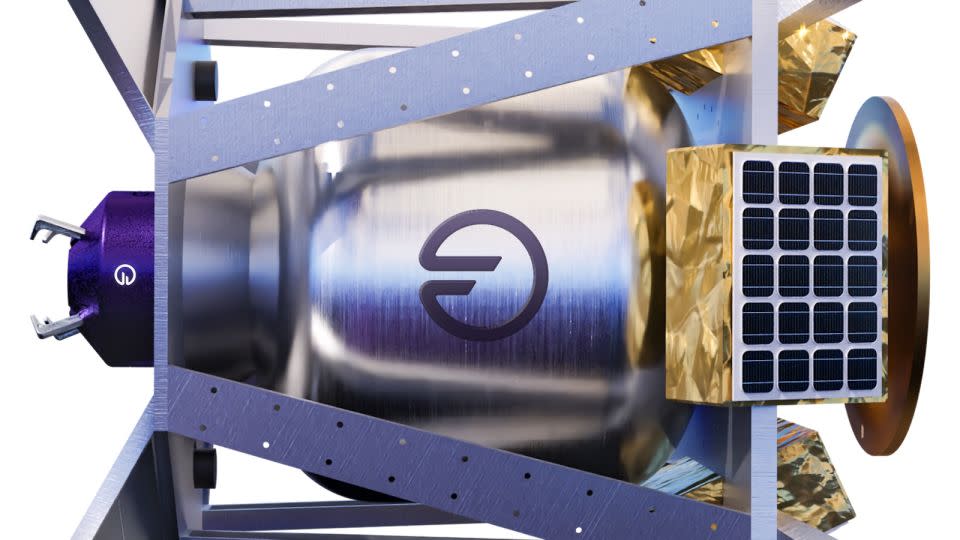

Orbit Fab has no plans to address the existing fleet of satellites. Instead, it wants to focus on those that have yet to ship, and provide them with a standardized port – called RAFTI, for Rapidly Retrievable Fluid Transfer Interface – that will greatly simplify the refueling operation, while keeping the price tag down.

“What we’re looking at is creating a low-cost architecture,” says Faber. “There is no commercially available fuel port to refuel a satellite in orbit yet. For all our ambitions for a space economy under pressure, really what we’re working on is the gas cap — we’re a gas cap company.”

Orbit Fab, which advertises itself with the tagline “gas stations in space,” is working on a system that includes the fuel port, refueling shuttles – which would deliver the fuel to a satellite in need – and refueling tankers, or orbital gas stations, from which the shuttles could pick up the fuel. He has announced a $20 million price tag for the delivery into orbit of hydrazine, the most common satellite propellant.

In 2018, the company sent two test beds to the International Space Station to test the interfaces, pumps and plumbing. In 2021 it launched Tanker-001 Tenzing, a fuel depot demonstrator that informed the design of the current hardware.

The next launch is now scheduled for 2024. “We’re delivering fuel into geostationary orbit for a mission underway at the Air Force Research Laboratory,” says Faber. “Right now, they’re treating it as a demonstration, but it’s getting a lot of interest from across the US government, from people who understand the value of refueling.”

Orbit Fab’s first private customer is Astroscale, a Japanese satellite servicing company that developed the first satellite designed for refueling. Called LEXI, it will install RAFTI ports and is currently scheduled to launch in 2026.

An original approach

According to Simone D’Amico, an associate professor of astronomy at Stanford University, who is not affiliated with Orbit Fab, on-orbit servicing is one of the keys to ensuring the safe and sustainable development of space. “Could you imagine land mobility infrastructure, roads and cities, without gas stations and car repair shops? Could you imagine single-use cars or airplanes?” he asks. “The development of space infrastructure and the proliferation of space assets is reaching a critical mass that is no longer sustainable without a paradigm shift.”

D’Amico also says there are many reasons this hasn’t happened sooner, including, until recently, a lack of perceived need given the limited number of spacecraft, and the fact that on-orbit servicing technology is only now viable from the point of view of the economy. advances in satellite miniaturization.

He believes that Orbit Fab is original, especially from a marketing point of view. “It is probably the only company in the world in a position to deploy ‘gas stations’ into orbit,” he says. “I think Orbit Fab’s approach is very visionary and could pay off in the medium to long term. However, it carries a high risk in the short term, as satellites must be designed with reusability and refueling in mind.”

Initially, Orbit Fab plans to find its market as a fuel supplier to companies, such as Astroscale, that plan to inspect, repair and upgrade satellites in orbit, or carry out debris collection. According to Faber, if this sector were to succeed it would be possible to convince the large telecommunications corporations, which operate a large number of satellites, to shape their business model and accept refueling and servicing.

He also says that once the launch and fuel delivery pattern into orbit is established, the next step is to start making the fuel there. “In 10 or 15 years, we want to be building refineries in orbit,” he says, “processing materials sent from earth into a range of chemicals that people want to buy: air and water for commercial space stations , 3D printer nutrient stock minerals to grow plants. We want to be the supplier of industrial chemicals to the emerging commercial space industry.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com