You are probably familiar with classic sauropod dinosaurs – the four-legged herbivores known for their long necks and tails. Animals like Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus and Diplodocus They have been standard fixtures in science museums since the 1800s.

With their small brains and huge bodies, these creatures have long been the poster children for animals destined for extinction. But recent discoveries have completely rewritten the doomed sauropod story.

I study a little-known group of sauropod dinosaurs – the Titanosauria, or “titanic reptiles”. Instead of becoming extinct, the titanosaurs thrived long after their famous cousins had died out. Not only were they big and ruled all seven continents, they held their own among the newly evolved duck and horned dinosaurs, until an asteroid hit the Earth and ended the age of the dinosaurs .

Perhaps the secret of the titanosaurs great biological success is how they combined the best characteristics of the reptilian and mammalian characteristics to create a unique way of life.

Moving with the continents

The Early Cretaceous Period, nearly 126 million years ago, began with the titanosaur, a time when many of the Earth’s land masses were much closer together than they are today.

Over the next 75 million to 80 million years, the continents slowly separated, and titanosaurs drift along with the changing formations, becoming distributed around the world.

There were nearly 100 species of titanosaurs, accounting for more than 30% of all known sauropod dinosaurs. They varied greatly in size. From the largest known sauropods ever discovered, including Argentinosaurus, Patagotitan and Futalognkosauruswhich exceeded 60 tons (54.4 metric tons) in weight and were larger than a half-truck, to the least known sauropods, including Rinconsaurus, Saltasaurus and Magyarosauruswhich was only about 6 tons (5.4 metric tons) and about the size of an African elephant.

Children to titans

Like many reptiles, the titanosaurs began life tiny, hatching from eggs that were no bigger than grapes.

The best data on titanosaur nests and eggs come from a site in Argentina called Auca Mahuevo, where 75 million-year-old rocks are exposed. The site contains hundreds of fossilized nests containing thousands of eggs, some so well preserved, scientists recovered skin impressions from ancient embryos.

The large number of nests found together, in multiple geological layers, suggests that the titanosaurs returned to this site several times to lay their eggs. The nests are so closely spaced, it is unlikely that an adult titanosaur would be able to move freely through the nesting grounds. Titanosaurs probably had a carefree parenting style, like many reptiles that lay a lot of eggs and don’t spend much time tending to the nest or caring for the young.

A titanosaur hatchling would have been about 1 foot (30 centimeters) tall, 3 feet (1 meter) long and 5-10 pounds (2.5-5 kg). Recent evidence from a site in Madagascar suggests that these little titans were born ready to rumble.

Fossil bones from the species Rapetosaurus which would indicate that by the time they were only knee high with a modern person, they were probably looking out for themselves. Microscopic data recorded deep within the bones shows the baby Rapetosaurus it is likely that they were looking independently for plants and that they moved much more nimbly than their lumbering adult relatives.

For the first hundred years of dinosaur science, paleontologists envisioned titanosaurs as giant reptiles that grew—and used reptile growth rates to predict their milestones. In this model of slow growth, even the smallest titanosaurs would take almost a century to reach their full size, which would mean that they would be relatively small for much of their lives. New evidence suggests that this growth pattern is unlikely.

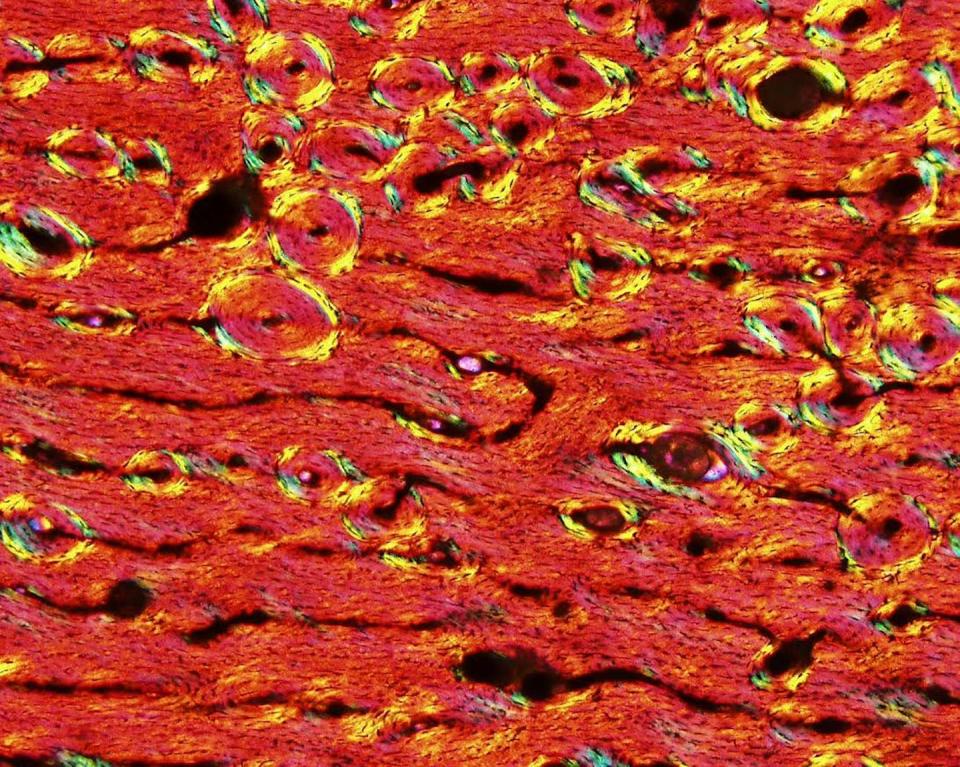

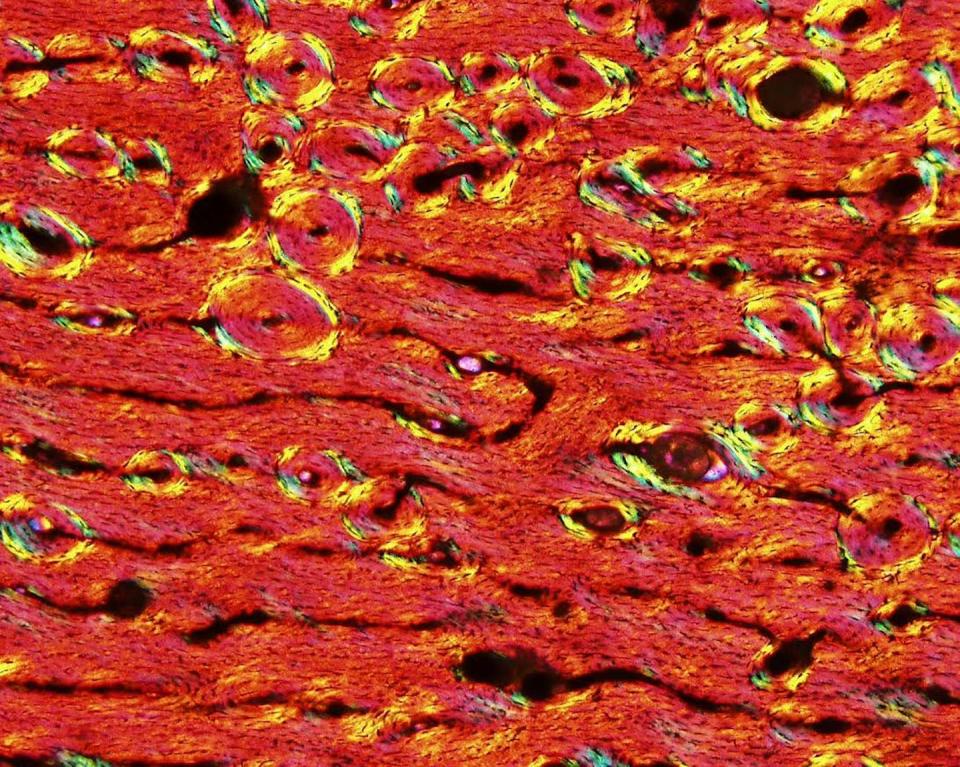

Scientists like me study the bones of titanosaurs at high magnification to better understand their growth. We look at the microscopic patterns of bone mineral as well as the density and architecture of the spaces where vessels and blood cells were.

The closer the blood supply to a bone, the faster that animal grows. These signatures are also present in living animals and can accurately indicate growth rates, anomalies and even age.

Bone data shows that titanosaur growth rates were on a par with mammals like whales—much, much faster than any living reptile—meaning they would have reached their massive adult sizes in just a few decades. Scientists do not know for sure how long the titanosaurs lived, but based on large land animals living today, the titanosaurs may have lived 60 years or more.

Fueled by plants

The rapid growth rates of sauropods were partly due to their body temperature. By studying the chemistry of fossilized teeth and egg shells, scientists determined that titanosaurs had body temperatures ranging from about 95 to 100.5 degrees Fahrenheit (35 to 38 degrees Celsius). That is higher than that of crocodiles and alligators, about the same as modern mammals and slightly lower than most birds, whose bodies regularly get as hot as 104 F (40 C).

Titanosaurs’ rapid growth rates were also driven by their prodigious appetite for plants. Microscopic patterns of scratches, wear and pits on their teeth show titanosaurs in Argentina fed on a varied diet rich in chalk, suggesting that they were feeding on plants found lower in the ground, where sediments would be found common.

In India, chunks of fossilized feces, otherwise known as coprolites, show titanosaurs ingesting everything from ground level plants all the way up to the leaves and branches of trees.

Like all dinosaurs, titanosaurs replaced their teeth throughout life. But data shows that they replaced each tooth about every 20 days for maximum efficiency, one of the highest tooth replacement rates known for a dinosaur.

If not for the asteroid impact 66 million years ago, these long-lived, incredibly diverse and wild animals would probably have thrived in places as far away as Madagascar, Romania, North America and even Antarctica. Instead, titanosaurs were among the witnesses and victims of the world’s latest mass extinction.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Kristi Curry Rogers, Macalester College

Read more:

Kristi Curry Rogers receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the David B. Jones Foundation.