Archaeologists have discovered one of the world’s largest collections of ancient art, showing giants and monsters walking the Earth.

In a remote area of South America, a British-led research team has discovered over a thousand prehistoric engravings – including the world’s largest examples of prehistoric rock art. However, the archaeologists believe that the examples found so far are only “the tip of the ancient artistic iceberg” – and that many more are still waiting to be discovered.

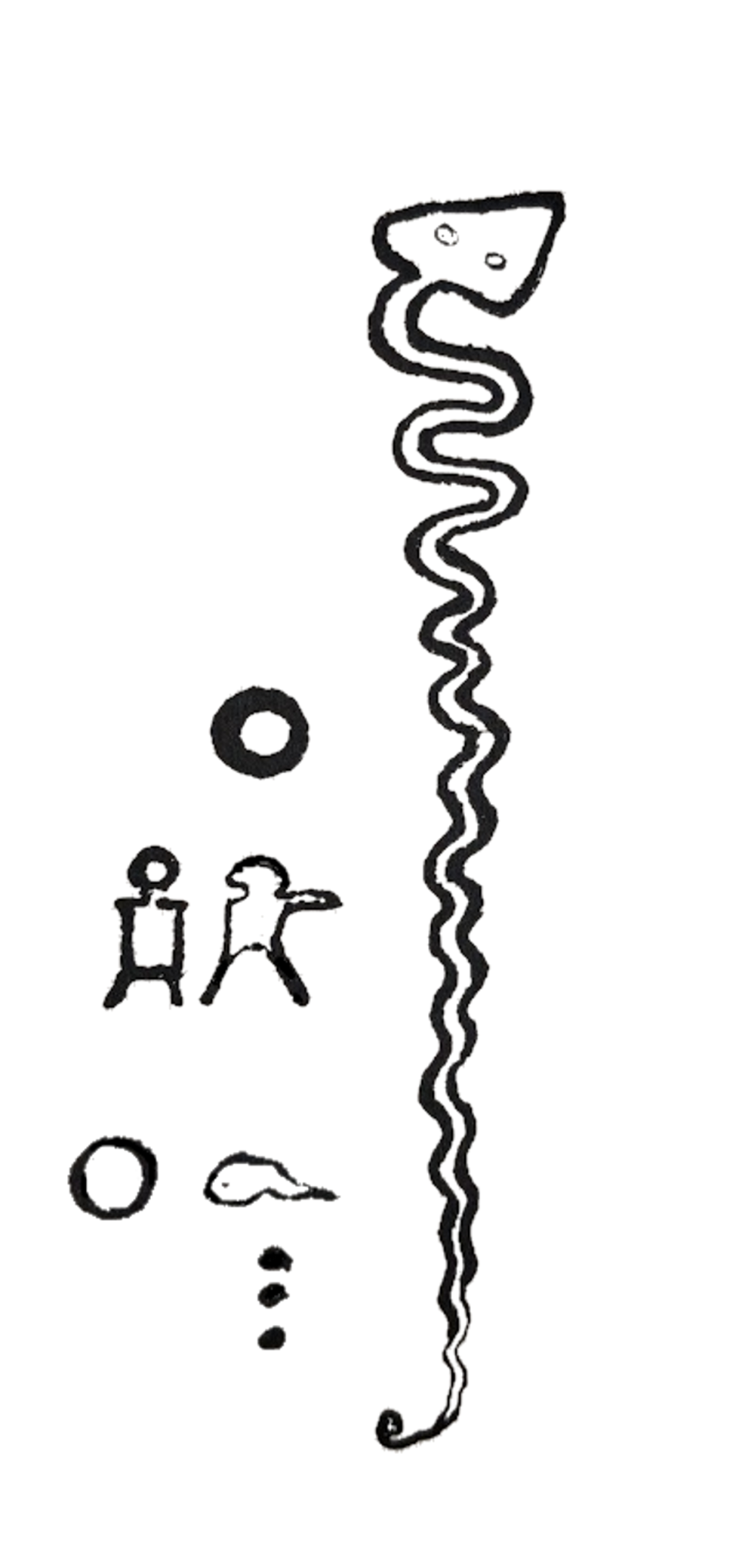

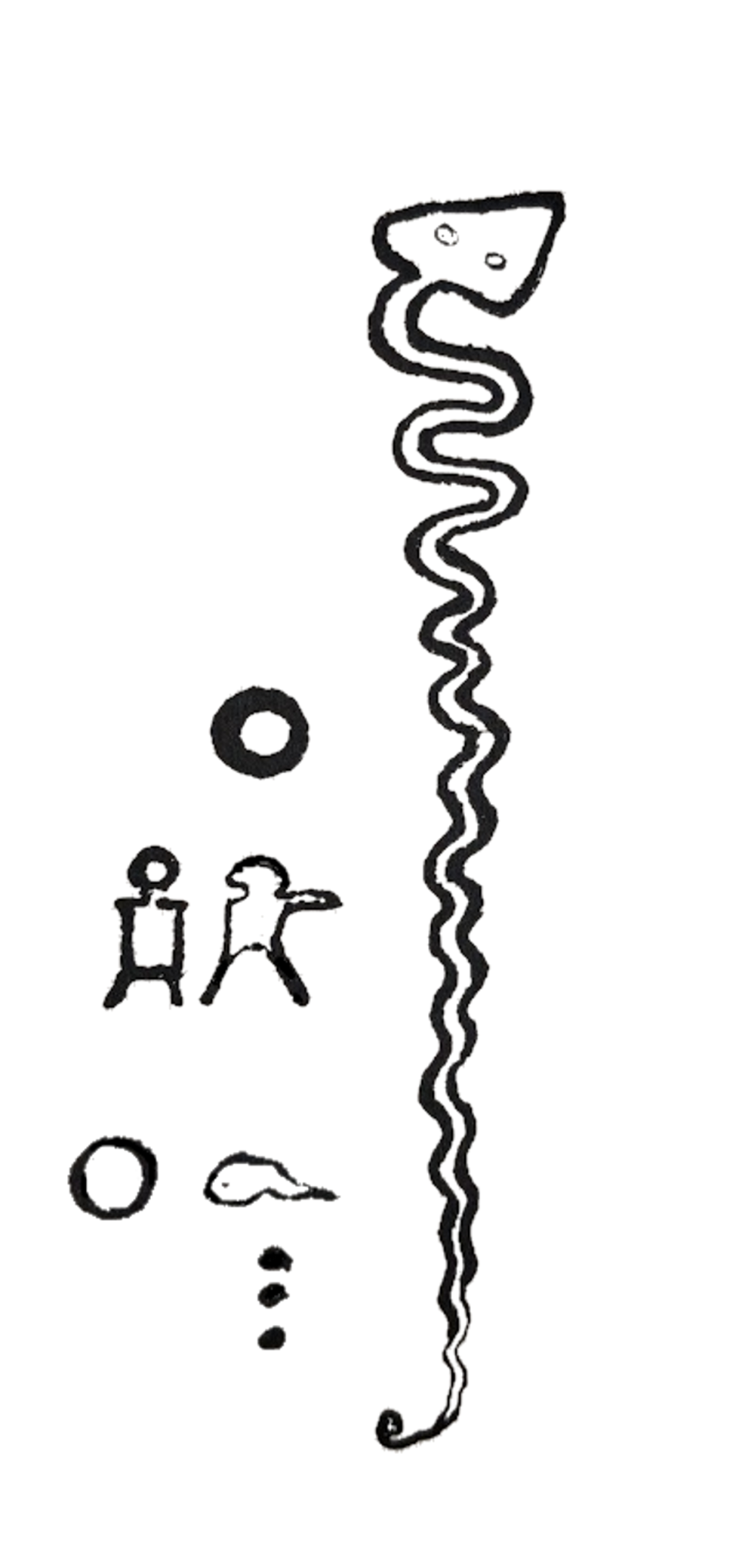

It is thought that there may be around 10,000 ancient engravings in the square mile area (smaller than the English county of Dorset). The largest found so far is a 43 meter long carving of a giant snake. Others depict giant centipedes, larger-than-life animals – and giant 10-metre tall human-like figures.

The engravings – found along the Colombia/Venezuela border – depict everything from stingrays and vultures to monkeys and crocodiles, from dogs and jaguars to turtles and frogs.

There are also a large number of geometric engravings (mainly concentric circles, grid patterns and dot-filled triangles), depicting objects that have not yet been identified.

It is one of the largest concentrations of rock art in the world – rivaling others such as the Dordogne region of France, northern Italian Alpine, Western Australia, and South Africa in terms of volume.

But the most unusual aspect of the engravings is the unique nature of some of them. About 60 of the 1,000 found so far have dimensions of more than 10 meters. In addition to the 43-meter snake, they include two 10-meter tall human-like figures (which could be spirits, or gods, or perhaps shamans), an 11-meter long centipede, and what probably four-. a huge insect a meter high (perhaps a butterfly).

“Our field research in Colombia and Venezuela, for the first time, is revealing, for the first time ever, an ancient culture that was largely unknown and unrecorded in this remote part of South America,” said one of the project leaders. , Dr Philip Riris from Bournemouth University’s Department of Archaeology. and anthropology. “We hope this will give the modern world an opportunity to appreciate the artistic and other achievements of the people who lived there hundreds of years before European colonization,” he said.

The giant snakes (seven of them, between 16 and 43 meters long) are of particular importance as they may be part of a much wider global “mega-snake” tradition.

Academic research published by many scholars over the years suggests that unlike most other belief systems involving animals, snake worship, known to anthropologists as philosophy, was a major once a global phenomenon. It appeared (and in some cases still appears) in religious systems and mythology in almost every part of the world – from prehistoric Europe and ancient Egypt to Aboriginal Australia and ancient America.

Classical Greek mythology was rich in supernatural serpent monsters and other serpent-related beings, as was the mythology of the Middle East, Europe, Mexico, Africa, China, Japan and India.

Snakes have often been associated with the creation of humanity or particular tribes; with immortality; and to cure the disease. Depending on the culture, they can be considered honest or evil (or capable of both) – and sometimes even seen as a symbol of royalty.

The unusually wide global distribution of serpent mythology and religious iconography suggests that the phenomenon is extremely ancient – and that people around the world, for possibly thousands of years, have felt compelled to soothe sergeants and specifically observed. This is certainly because snakes were (and still are) a greater threat to humans than any other animal (apart from disease-carrying insects).

Even today, around 20,000 people die each year from venomous snake bites (compared to just 100 per year from lion attacks and 500 per year from encounters with crocodiles). In addition, snakes bite and ingest 400,000 or so other people each year, even if they do not die.

In ancient times, when people lived much closer to the natural environment (and continuously hunted and gathered in that environment), snakes were certainly, proportionately, an even greater threat to mankind – a threat to need to be cheerful and therefore worship, worship. and plaque.

Like the newly discovered examples of Colombia and Venezuela, other ancient cultures often depicted snake deities or spirits as truly monumental creatures. In California, Ohio, Peru and other places, there are manifestations of truly gargantuan snakes slithering across local landscapes. The largest, a 900-year-old 411-meter-long earthwork representing a giant snake, can still be seen on a hilltop in southern Ohio.

The newly discovered Colombian engravings were made by ancient Native American people – probably between about 700 and 1000 AD. They are among the most difficult to access examples of prehistoric outdoor art in the world. That’s because prehistoric artists often carved them so high up on near-vertical cliff faces. It would be challenging, difficult and dangerous work.

The giant snake is 43 meters long, for example, located three quarters of the way up a cliff 200 meters high. Some evidence suggests that it functioned as an oracle in ancient times – allowing the snake to “speak” to the local community, through a shaman or other intermediary (as oracles functioned in other parts of the world, including the Ancient Greece and ancient Greece. Egypt).

The thousands of engravings found so far by the archaeological team are located in 157 clusters along a 110 mile stretch of the Orinoco River. The first European explorers to enter the region were German and English treasure hunters from the 16th century, searching for the wonderful gold of El Dorado. Those adventurers (including Sir Walter Raleigh of England) did not find the legendary city, or the gold. But now, modern explorers have managed to uncover an archaeological treasure – massive works of art that will help change the academic world’s understanding of a fascinating, long-lost ancient culture.

“We hope that our research work will help ensure that the extraordinary artistic heritage of the Orinoco valley is protected, and that local indigenous and mixed-heritage communities will be involved in that process,” said Riris.

A brand new paper, devoted entirely to the description of newly recorded and globally important Orinoco rock art, is being published on Tuesday – written by three key archaeologists of the Orinoco project: Philip Riris of Bournemouth University, Jose Ramon Oliver from University College London, and Natalia Lozada Mendieta from the University of the Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. Published by the journal of archaeological studies in the United Kingdom Antiquitiesit will be available for free online.