Even on a Sunday, amidst the weekend traffic, the drive from Orlando to Tallahassee feels like quite an odyssey. It’s only 250 miles, but Interstate 10, in particular, seems to stretch on forever – to the point where I soon wonder if I’ve lost my turn, gone far beyond the Florida Panhandle , and I’m halfway through 2,460 on the highway. -mile trek to Santa Monica and the California coast. By the time I slip into town, the sun is setting, and it seems like days, rather than hours, have passed since I left Mickey Mouse behind.

It’s not entirely fair to say that Florida’s capital is in the middle of nowhere. It is 25 miles south of Amsterdam – a small town just over the “border” in nearby Georgia. It is 20 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico, at Apalachee Bay; 50 miles from the thick treeline of the Apalachicola National Forest; 105 miles from the beach resorts of Panama City Beach.

But it is certainly fair to say that it is not very big. It is only the eighth most populous city in the third most populous state in the US, adding just 202,000 residents to the state’s total of 23 million – of whom 70,000 are university students. Love Florida – Fort Lauderdale hotels, Orlando flea markets, mansions and West Palm Beach bank accounts. But Tallahassee, his administration suggested, is small.

And if it’s not quite in the middle of nowhere, then it’s definitely in the middle of something. Specifically, the trip between her Florida sister cities Pensacola (197 miles to the west, out toward the Alabama state line) and St. Augustine (202 miles to the east, on the Atlantic coast). All of this balance is part of Tallahassee’s story, and is the main reason – in its modern form – that it came into existence exactly two hundred years ago.

It’s a story intertwined with Florida’s own story. The “Sunshine State” became part of what is now the United States of America – originally as the “Florida Territory” – on 30 March 1822, having been ceded to America three years earlier (through the Adams Treaty -Onis) by a Spaniard who could maintain more resources.

At the time, the region was very different from the destination that welcomes around 1.5 million people on holiday from Britain every year. “City life”, such as it was, was largely confined to the two earliest settlements carved out by the Spanish conquistadors – Pensacola in 1559 (and again, after catastrophic hurricane damage in 1698); Saint Augustine in 1565.

Both cities wanted to take a central role in running the new Florida. Neither wanted to cede ground or initiative to the other. The first session of the Legislative Council of the Florida Territory was held in Pensacola on 22 July 1822 – a great inconvenience to the representatives of St. Augustine, who were forced to sail around the entire peninsula of Florida, a trip that took 59 days, in order to be present . The second session – held in St. Augustine – required a trip to the equally dangerous Pensacola.

Clearly this could not continue. Other options were discussed. And an agreement was reached. Anhaica, the main town of Florida’s Apalachee people, stood halfway between the two, and was an ideal compromise. Or, at least, it would have been if it had not been razed by Andrew Jackson, the future seventh president of the USA, in 1818 – one of a series of brutal body blows that fell on the native population of the region in the 19th century. With a certain grim irony, the capital that rose among the still-smoking ruins had a local name: “Tallahassee” is a Muskogean word, loosely translated as “old fields.” On March 4, 1824, territorial governor William Duval approved it as the new capital of Florida. The third session of the legislative council was held in a crude log cabin.

Take a look at the state’s map, and you might ask a reasonable question: why is its capital so far north on purpose? The answer is that, in 1824, in terms of major population centers, Florida meant northern Florida. Orlando would not exist (and until 1843, as the village of Jernigan) the first tracks of Miami would not come until 1858 – and development would not really take place until Henry Flagler completed his railroad down the Atlantic coast in 1912 .for the most part, the southern part of the peninsula was swampy, sparsely populated and – as far as the “New World” settlers were concerned – very dangerous. The Third Seminole War of 1855-58 took place in and around the Everglades, as the native Florentines who had not been relocated by Jackson – or forcibly transported to Oklahoma – fought hard to protect what was left of their ancestral lands.

Tallahassee was not an immediate success. When he visited it in 1827, the American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson was horrified, describing it as “a grotesque center of land speculators and desperados”. But when the United States became a full state in March 1845 – Florida joined the club as the 27th member – so even the capitol building played a role.

He is still – although, at first, walking east through the town, I am struggling to see him, so bad is his successor. Unusually, Florida has two capitols, one next to the other. The modern version – a 25-storey, 345ft (105m) tower of no apparent beauty, opened in 1977 – blocks the sight lines to its historic predecessor from certain angles. It would prevent him completely from having a flutter of nostalgic soft-heartedness, rare in a country that has always been ready to tear down the old and put up something new, which is not stopping the bulldozers.

The decision to hold an open house on March 30, 1978, which would allow Floridians to visit their original capital, attracted 2,000 visitors and many letters demanding its preservation. Three months later, the governor of Florida at the time, Reubin Askew – who favored demolition – signed the legal protections that enshrined the structure as a museum.

This has proven to be the right course of action. An elegant piece of architecture in the neoclassical tradition of American capitols, the old statehouse wears its heritage with grace. In the lobby, a black-and-white photograph captures him in those early moments in 1845, a picket fence in front – there to keep out, not people, but the cattle eager to graze on the lawn. Above him, the inside of the dome is a blur of color – courtesy of 12 stained glass panels that are decidedly Art Nouveau, though their ancestors are replicas from 1902.

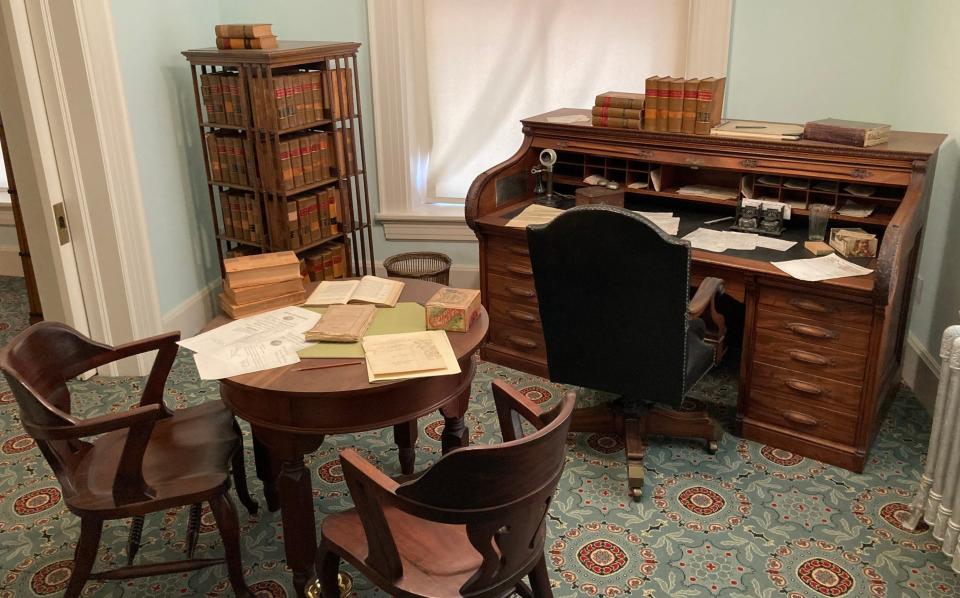

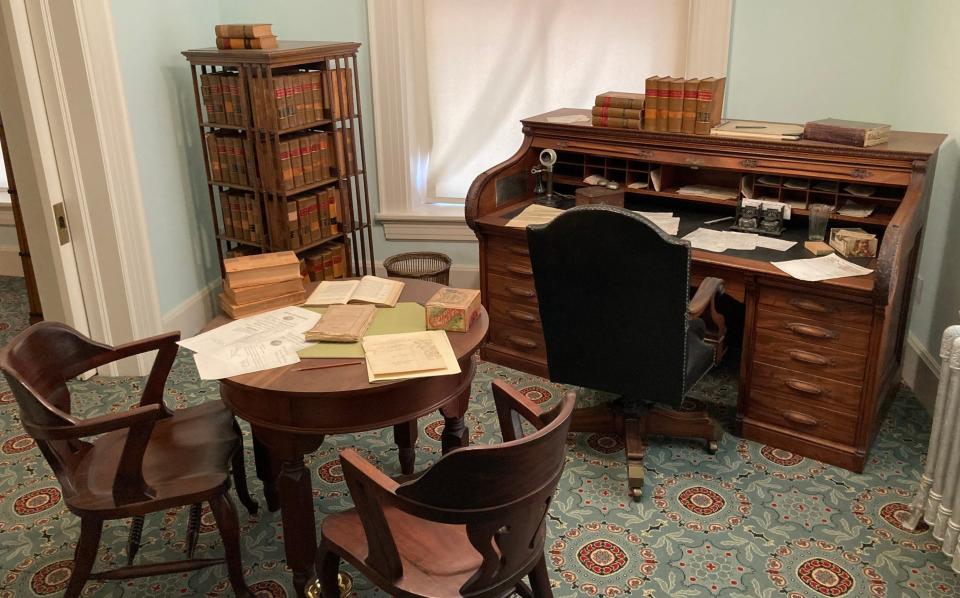

Much of the building is frozen frame as it was that year. The 122 years in question fall away as I walk through them. You can practically hear loud applause in the former Supreme Court, where the seats for six judges remain empty; almost hearing the pressure of the constant debate in the chamber of the Senate and the House of Representatives that was once there. The Governor’s office, meanwhile, recalls its 18th incumbent, William Jennings, who sat behind the desk displayed here between 1901 and 1903. His tenure would have been shorter had his secretary not attempted assassination to do on 17 December 1902, wrestling with the. the gunner landed his barge into the room a week before Christmas.

The museum does not shy away from hard facts. Another room, as an artefact, shows the exposed racism of segregated America – a bathroom door (from 1949) bearing the sign “White Ladies”. Political tension is also evident, through one of the ballot boxes from the Florida recount that decided the 2000 presidential election between George W Bush and Al Gore. The building is also happy to admit that its location, a pragmatic choice in 1824, has become increasingly controversial in the following 200 years. “[It is] resolution that the Ocala Woman’s Club urgently favors moving the capital of Florida to a more central location in the state,” reads a protest letter dated April 30, 1921 (Ocala, 80 miles northwest of Orlando which, conveniently, is directly therefore. central location). Tallahassee has been reversing this notion “as recently as 1967, when senator Lee Weissenborn led calls for relocation, before the new capitol was built.” That ship has certainly sailed – even though Tallahassee is still a small town with a big purpose.

Madison Social, an inviting bar-restaurant that overlooks the Florida State campus playing fields, has just a sweet buzz; craft beer specialist The Proof Brewing Company has a very local vibe – so much so that its signature ale, EightFive-O, takes its inspiration from the city’s phone code. With the gardens of Alfred B. Maclay State Park, up on the northern edge, there is a leafy calm far away from ordinary urban life, couples strolling under cypress trees in a space shaped like a dream retirement home by the title New York financier in 1923. Perhaps, even here, you are not quite in the middle of the action – but among the bubbles of birdsong, you realize that you cannot be far from it.

Fundamentals

Tallahassee has its own airport. You can’t fly in direct from the UK, but there are convenient connections to Miami and Fort Lauderdale – as well as Atlanta in Georgia.

Hotel Indigo (826 Gaines Street West; 001 850 210 0008; ihg.com). Doubles from £167.

Admission is at the Florida Capitol Historical Museum (flhistoriccapitol.gov).

For more information, see visittallahassee.com; tallahasseeleoncounty200.com; visit florida.com; visittheusa.co.uk

Go with the experts

Realistically, for British tourists, Tallahassee is likely to be part of a longer road trip. It is a two-day feature of the 14-night “Discover the Real Florida” itinerary sold by Bon Voyage (0800 316 3012; bon-voyage.co.uk) – from £2,125 per person, including flights.