“That’s North America just out your right window,” came the pilot’s voice as we began our descent. “And the European Union is below us on the left.”

I looked down, over waters blooming with humpbacks, and felt suddenly – unexpectedly – that I was on the edge of Europe. Because, you see, it’s possible to fly from North America to France in less than an hour – and you won’t even need a hypersonic jet or a DeLorean time machine.

All you have to do is board a flight up the east coast of Canada from Saint John, Newfoundland, as I did earlier this month. Just 45 minutes later, you’ll be rewarded with awesome Gallic and cuisine, all without another Brit in sight. The destination? Saint Pierre and Miquelon, where everything you hear, see and taste is as French as possible.

In black and white, Saint Pierre and Miquelon is a “self-governing overseas territorial collection”, but to the 6,000-odd residents who live on the archipelago, it is France, pure and simple. Some days, the colors of the bay in the capital Saint-Pierre resemble the Côte d’Azur, Miquelon’s sand-backed beaches as golden as those on the Ile de Ré.

But when I arrived, the Atlantic was gray and bleak, bleak on black, and it felt like Brittany, Normandy or the Basque Country, foggy and out of focus. Fittingly, the islands were settled by cod fishermen from those same regions in the early 17th century when they came to set up their rebellion on the Great Bank. Today, there is great pride in all of this.

Residents of the archipelago often worry about misrepresentation, and it’s little wonder. Quite simply, despite the geography, they are not Canadian, Newfoundland or Quebecois, but as French as Napoleon – and their island remains a rock pool of tradition. “That’s how we like it,” said my guide Agathe Olano, as we took the 90-minute ferry from the petit port of Saint-Pierre to Miquelon on my first day. “Our remoteness from Paris fosters closeness and everyone knows everyone.”

As our ferry steered through the foaming Atlantic, Agathe filled me in on the details. The currency in Saint Pierre and Miquelon is the euro. It is faster to post a letter to France than to Canada, only a dozen miles away. All supplies come by sea or air, and mostly not from Canada either. Shops promise a traditional French two-hour lunch break. Bastille Day is a public holiday. Everyone smokes. This is France.

There is even a guillotine in the collection at the L’Arche Museum and the Archives in Saint-Pierre. In a macabre, if mocking, Pythonesque case, Agathe told me, the decapitation device was not sharp enough, so the only time it was used in North America back in 1889, the executioner used a knife to do the job. finish. Currently, the galleries remain closed as the building’s sail-shaped roof is leaking.

Speaking of rather sharp blades, Peaky Blinders Google searches for the colony of French remains have also increased. Miquelon featured heavily in the TV show’s storyline for its six seasons, and the archipelago played a central role in the efforts to smuggle alcohol during the prohibition era in America. The names of gangsters like Al Capone, who carried out bootlegging operations on Saint-Pierre, can now be seen on tours during the summer. Today, so the story goes, there are still thousands of whiskey bottles sunk to the bottom of the sea.

By the time we arrived in Miquelon, it was a little after 11am, and yet the newly opened boulangerie – huge news for the people of the parish – still had a queue going out the door. It could be a scene straight out of the Marais district of Paris. Later, at the grocery store – surrounded by shelves of wine, jars of confit de canard and foie gras made at a Miquelon farm – Agathe put an imported cheese into her basket.

The feeling of being in the right place, but on the wrong side of the world, was much the same over lunch at Le Snack Bar-à-Choix. I paid the bill for my buckwheat galette and was given a blank look when I answered in English by mistake. A scene that was so common from a thousand bistros, but like parts of France, these islands roll out the red carpet for anyone.

That evening, before catching the last ferry back to Saint-Pierre, we explored Miquelon and its neighbor to the south, Langlade, connected by a tombolo sandpit. The interior is defined by peat bogs and mossy hills where horses are allowed to roam freely throughout the summer. On the shore are dune-backed lagoons, where seals and puffins, fondly called “le macareux moine” in French, go nesting every summer.

There is also a wooden Catholic church, where a canoe hangs over the nave; trawler fishing boats and traps; shipwreck at the entrance to the village. Always, the sense is that the locals are anchored in the sea.

The ferry slipped back to Saint-Pierre as Friday afternoon turned into evening. I boarded and ate at Le Bar à Quai, tucked away in a gunwales-filled waterfront area with bistros and bars. With everyone out smoking, flirting or killing, the restaurant was almost empty and the hints of marine life – half-glittered ropes, a painted picture of a lighthouse, a loose fishing net on a staircase – were felt fell straight from the pages of Jules. Verne’s novel.

The harbor was full of life, so it was halibut and coquilles St Jacques for dinner with Chenin Blanc and crème brulée. By then, Agathe and her friends showed up for a birthday party, and another bottle was opened. Next door, at Le Rustique, the patrons spilled out into the streets. The danger of eating and drinking too much felt like a threat in Saint-Pierre.

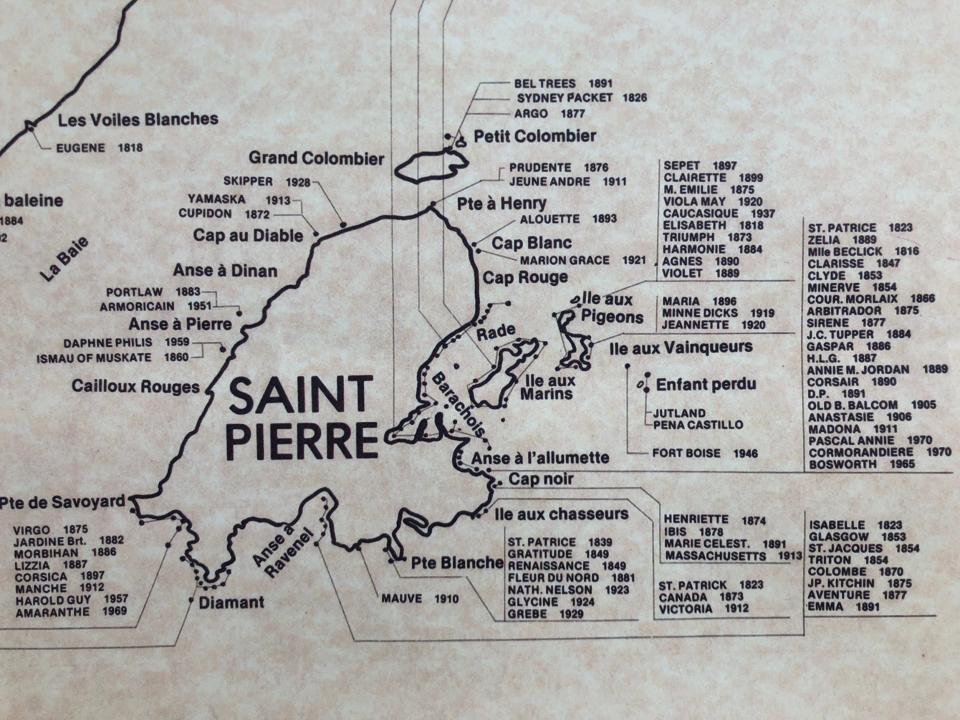

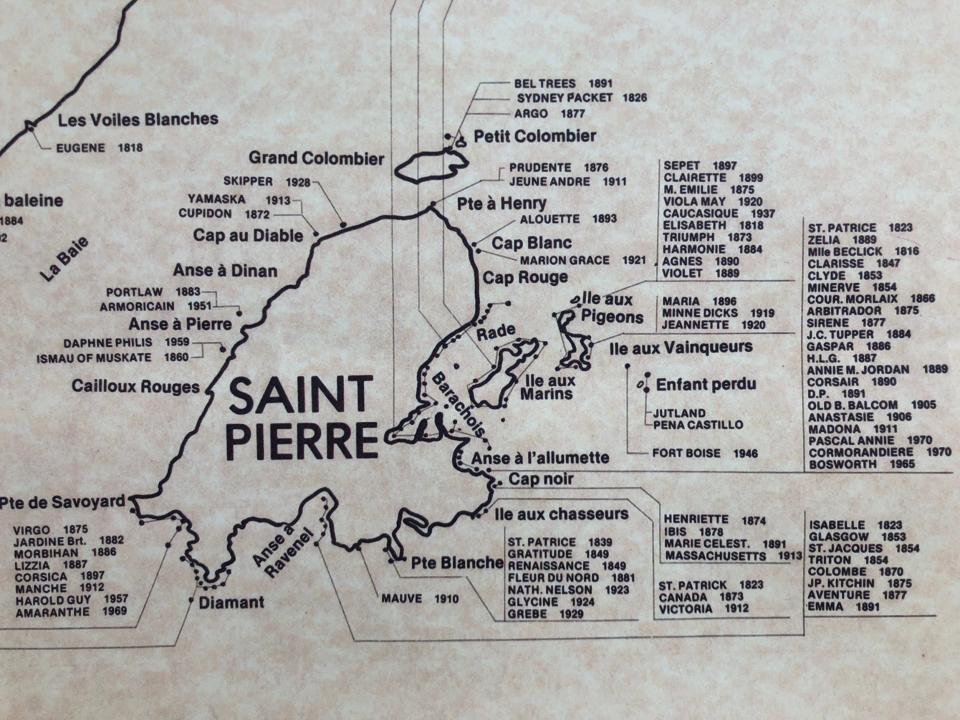

Another highlight was the morning ride around the Cap au Diable loop to Le Trépied at 207m. The views across the Atlantic seemed to transport me up to the highest summit on the island, past inky-dark ponds and tufts of sweet gale, sheep laurel and wintergreen bursting with berries.

At one point, my walking guide, Gilles Gloaguen of Escapade Insulaire, and I stopped to look for a white-tailed deer on a hillside. At the top, we had a bird’s eye view of the French-speaking world all to ourselves. The air smelled of the day on the sea. “This is our Mont Blanc,” said Gilles, as we looked at Newfoundland up close. It felt so much further away.

Before my return flight back to Canada, I spent my last morning looking out from Saint-Pierre’s Point aux Canons Lighthouse, the sun streaming across the horizon. Just 10 minutes across the bay was the sliver of L’Île-aux-Marins, a ghost island of ancient innocence since its fishing community abandoned it in the 1960s.

Later in the summer, there are tours of her crooked houses and church, but just then it was empty, lifeless, exhausted. Even the harbor around me thrummed with stillness. It was a Saturday and, fittingly enough, with no one else around, it was a last chance to enjoy France – or lay it – completely alone and in a completely different way.

Basics

Mike MacEacheran was a guest of Tourism Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (en.spm-tourisme.fr) and Legendary Coasts of Eastern Newfoundland (legendarycoasts.ca). Auberge Quatre Temps has doubles from £84, including breakfast (00 508 41 43 01; aubergequatretemps-spm.com). The ferry from Saint Pierre to Miquelon costs £20 return (spm-ferries.fr). Fly to St John’s from London Gatwick with WestJet, from £319 return (May to October only; westjet.com). From Saint John, fly with Air Saint-Pierre, to Saint Pierre, from £305 return (airsaintpierre.com).