-

Spaceships burn up in the atmosphere leaving behind metal particles.

-

Scientists are racing to find out if that has an effect on the climate.

-

One risk is that these particles could spark rainbow colored clouds that damage the ozone layer.

Satellites and spacecraft are burning up in our atmosphere leaving metal particles in the stratosphere – and scientists worry it could harm our planet.

About 10% of the particles floating around the stratosphere now come from the aerospace industry, and we don’t know if this could affect the climate.

One risk is that these new particles could spawn polar stratospheric clouds, which are spectacular rainbow-colored clouds that could damage the ozone layer, experts told Business Insider.

“This is a good indication of how important it is to have basic research in the stratosphere,” said Daniel Murphy, a research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chemical Science Lab, who led the particle survey. , with BI.

“There’s a whole phenomenon here that we didn’t expect and we don’t fully understand the implications,” he said.

Stratospheric particles can shape the ozone layer

Remember the ozone layer? If you were around in the 80s, that was probably the period you were associated with.

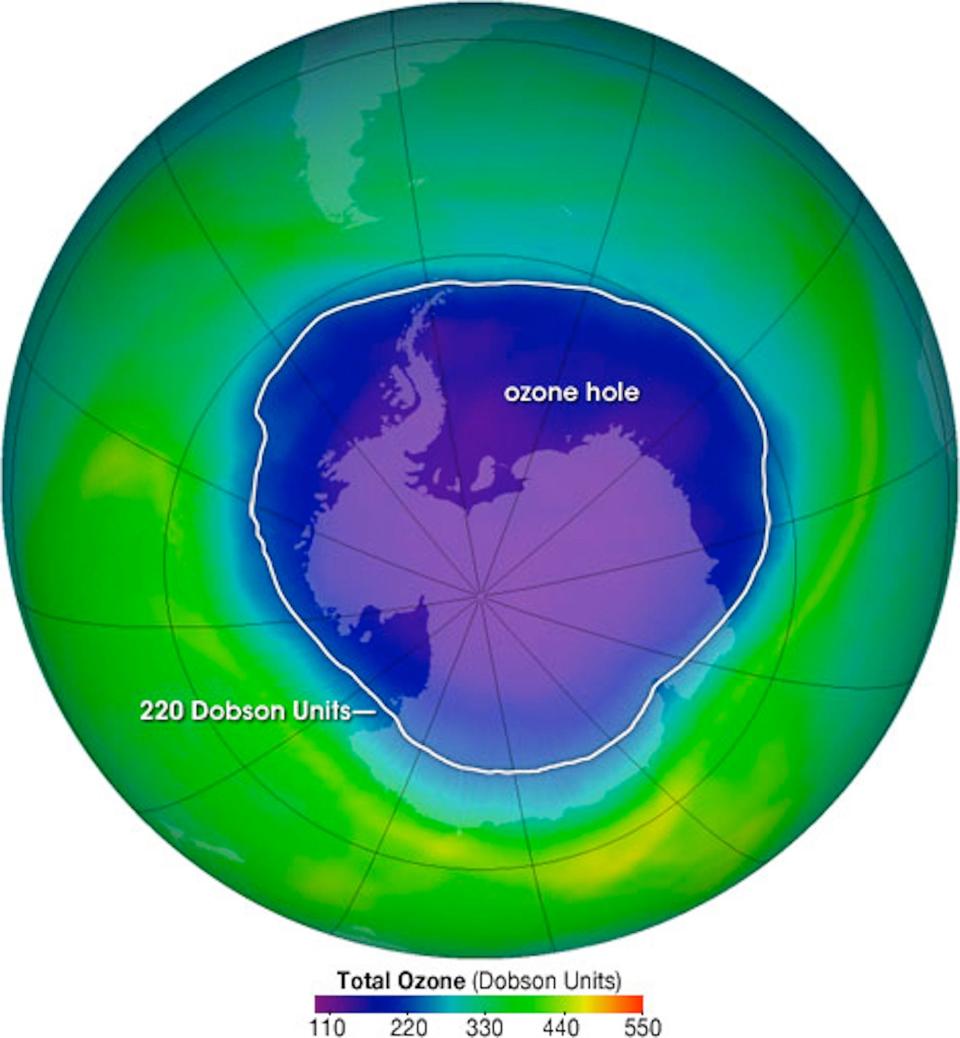

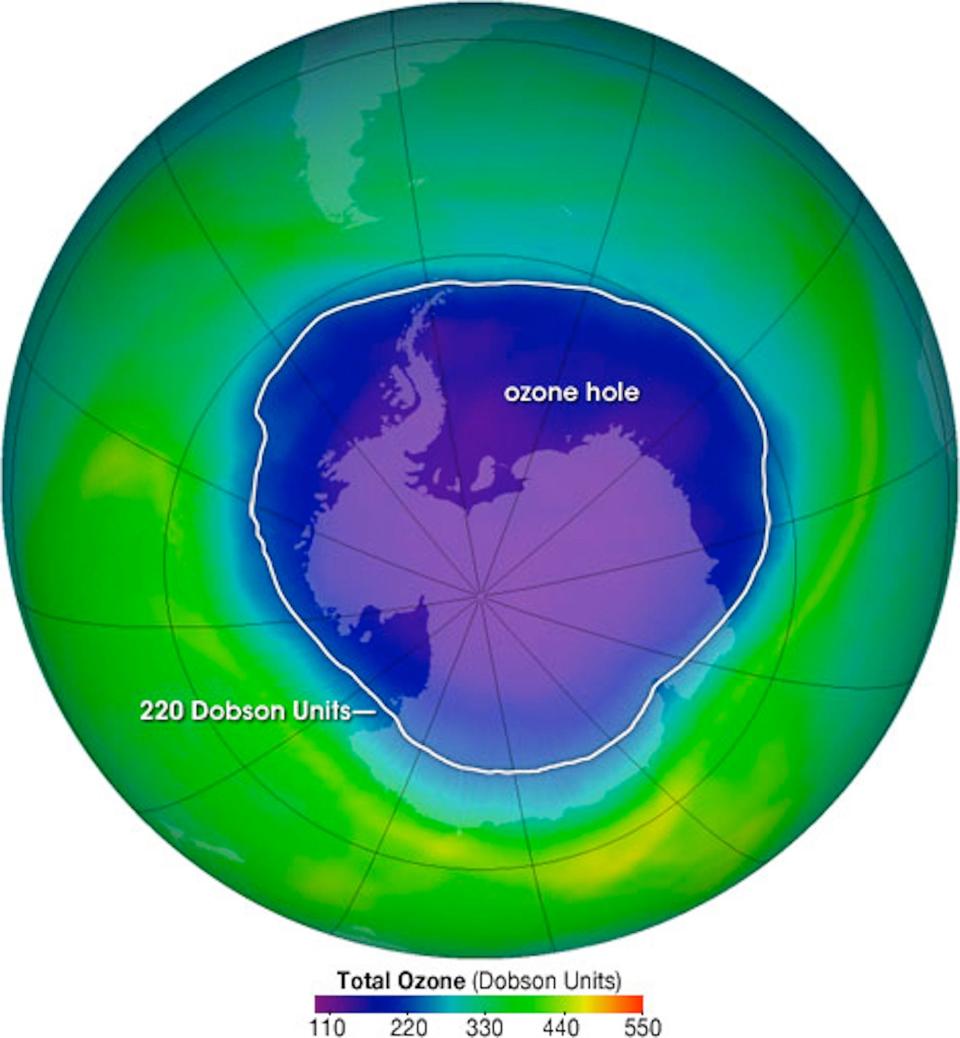

This vital layer of the atmosphere, which is mostly in the stratosphere, protects us from ultraviolet radiation from the sun. It often splashed across the headlines about 40 years ago when scientists raised the alarm about gaping holes growing over the poles caused by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) rising uncontrollably into the atmosphere .

The ozone holes are not making the news as often today. Thanks to the Montreal Protocol of 1987, a global agreement that laid out a path to phase out ozone-depleting gases, they are steadily recovering.

Still, they are not gone. In September 2023, the hole above Antarctica grew to the sixth largest size ever seen before returning, likely due to particles spewed by the 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga underwater volcano.

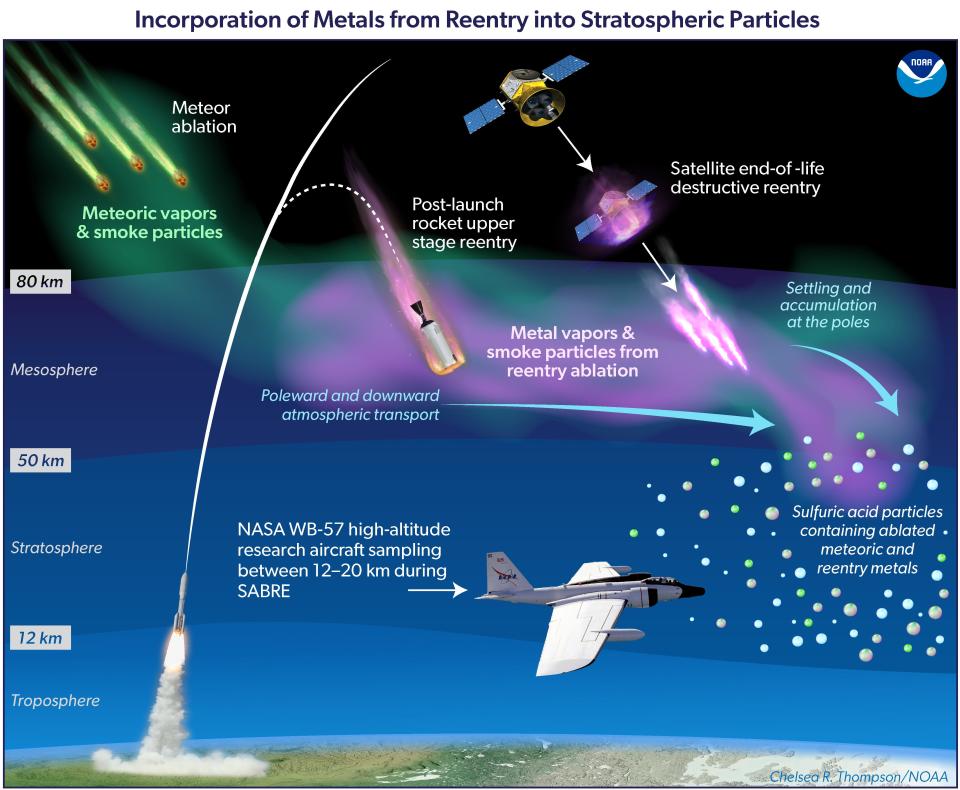

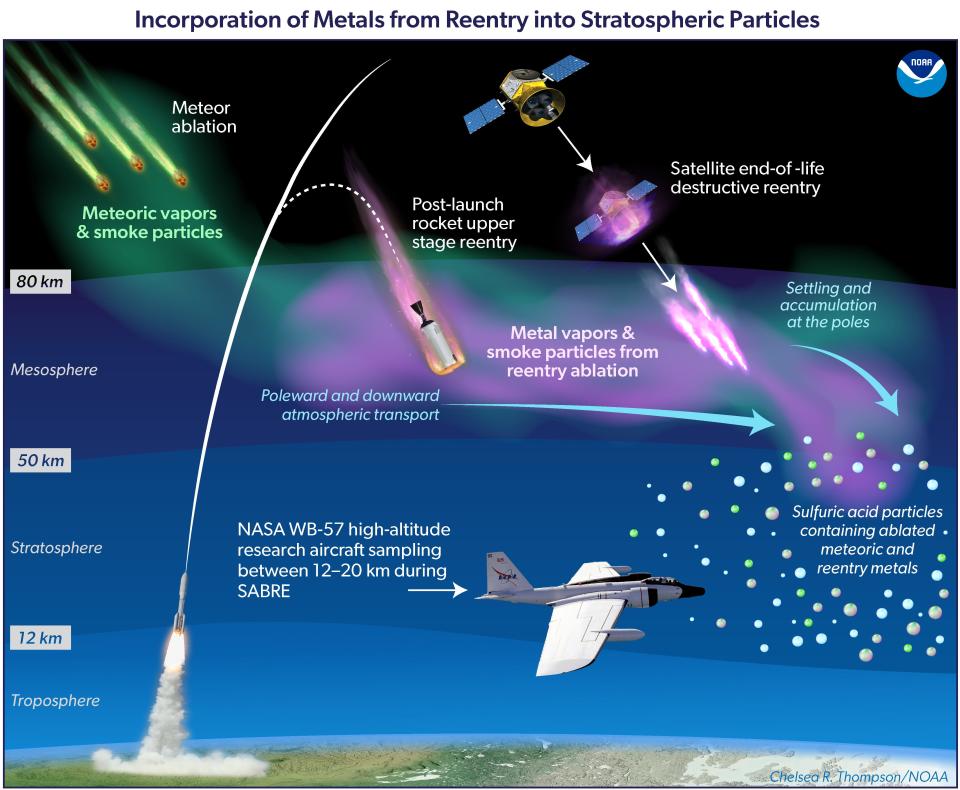

That’s why it’s important to keep track of particles in the stratosphere. These nanometer flies, which come naturally from a meteor crashing into the planet, can dramatically change the chemistry of the stratosphere.

Clouds do not usually form in the stratosphere, as it is much drier than the troposphere, where most clouds are born.

By introducing elements you wouldn’t normally see in the sky, such as metals, these particles can combine with the naturally occurring sulfuric acid in the stratosphere to create a chemical reaction that can cause passing water vapor to suction, which creates ice crystals.

This, in turn, can trigger a chain reaction that creates rainbow colored polar stratospheric clouds.

On their own, these amazing clouds are harmless, but when mixed with man-made gases, they can be terrifying. The edges of the clouds provide perfect conditions to turn harmful chlorines and bromides into their active, ozone-depleting form.

Metals from satellites and spacecraft are evaporating into the atmosphere

Murphy and his colleagues recently surveyed the state of stratospheric particles over Alaska using a sensitive detector aboard NASA’s WB-57 high-altitude research plane.

The results, published in the peer-reviewed journal PNAS in October 2023, showed that natural causes could not explain about 10% of the stratospheric sulfuric acid particles they picked up.

“We weren’t really looking for spacecraft, but it was clear in the data that there were elements that couldn’t have come from the meteors,” Murphy told BI.

The particles were “too much aluminum, too much lithium, too much of some other elements coming from meteors,” he said.

Two elements found in the particles, niobium and hafnium, were particularly surprising, Murphy said.

These do not occur naturally, but must be refined, the scientists said.

“The combination of aluminum and copper, plus niobium and hafnium, used in high-performance heat-resistant alloys, showed us the aerospace industry,” said Murphy.

At the moment, we don’t know what these new particles could do. But scientists are keen to figure it out.

“This is a new problem and we’re just starting to understand it,” Murphy said.

They may be able to spark polar stratospheric clouds. If so, this could be a big problem in the short term, Martin Chipperfield, professor of atmospheric sciences from the University of Leeds, UK, told BI.

“The timescale for the ozone hole to disappear is around 2060 based on current predictions because the chlorine is going down very slowly,” said Chipperfield, who was not involved in the study.

“So that gives a lot of scope in the short term, if we’re increasing the burning of space debris significantly over the next few years, for the ozone hole to get worse before it gets better,” he said. .

These new particles may also migrate to the troposphere, where they may influence the formation of cirrus clouds. Unlike other clouds, cirrus clouds trap heat in our atmosphere, potentially exacerbating the climate crisis.

It is also possible that the particles could create an entirely new phenomenon. Or they could do nothing.

Their composition is unique, so it is not clear what to expect. Murphy said scientists will need to conduct experiments in the laboratory to test this.

“It’s very important to understand because the space industry is growing so fast,” Murphy told BI.

“If there are impacts, you’d better understand it now before it grows than after it’s already grown a lot.”

We are realizing how little we know

With launch costs falling, the number of satellites orbiting the planet is expected to increase to over 50,000 by 2030, up from around 8,000 now. Many of these satellites are expected to have a short life span.

“If you multiply those numbers out, a satellite will be re-entering the atmosphere every hour on average,” Murphy said.

In the coming years, Murphy and his co-authors estimate that 50% of the particles in the stratosphere could be aerospace debris, making understanding what they do even more urgent.

Decommissioning spacecraft is only part of the equation, Chipperfield said.

“There is an increase in the number of rocket launches for small satellites and tourism, which burn kerosene or other fuels that are emitted into the atmosphere. Then some satellites and orbiters have a fuel like iodine that can come back into the atmosphere. And then the decline, ” he said. said.

“I think the whole life cycle of satellites is certainly watchable, and this burn is part of that,” Chipperfield said.

Scientists are also seriously considering engineering the atmosphere to help protect our planet from the sun’s heat by sending billions of particles of sulfuric acid into the stratosphere.

For Murphy, this shows how little we know about how humans are affecting the stratosphere as more prey takes to the skies.

“That there were still surprises in our understanding of the composition of particles in the stratosphere is relevant to conversations about adding more,” said Murphy.

Read the original article on Business Insider