-

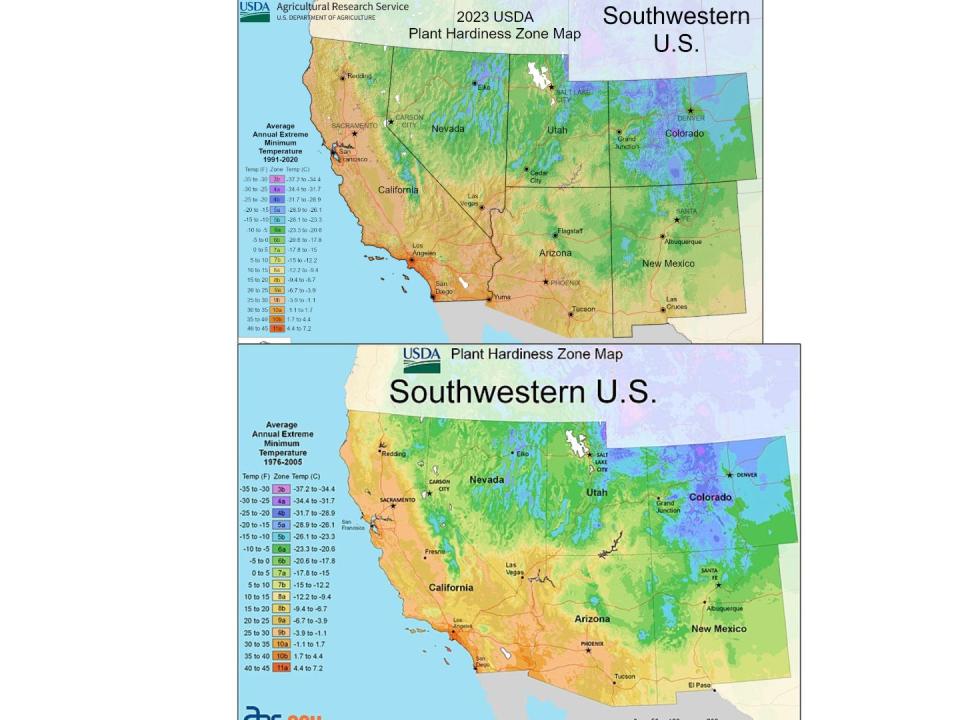

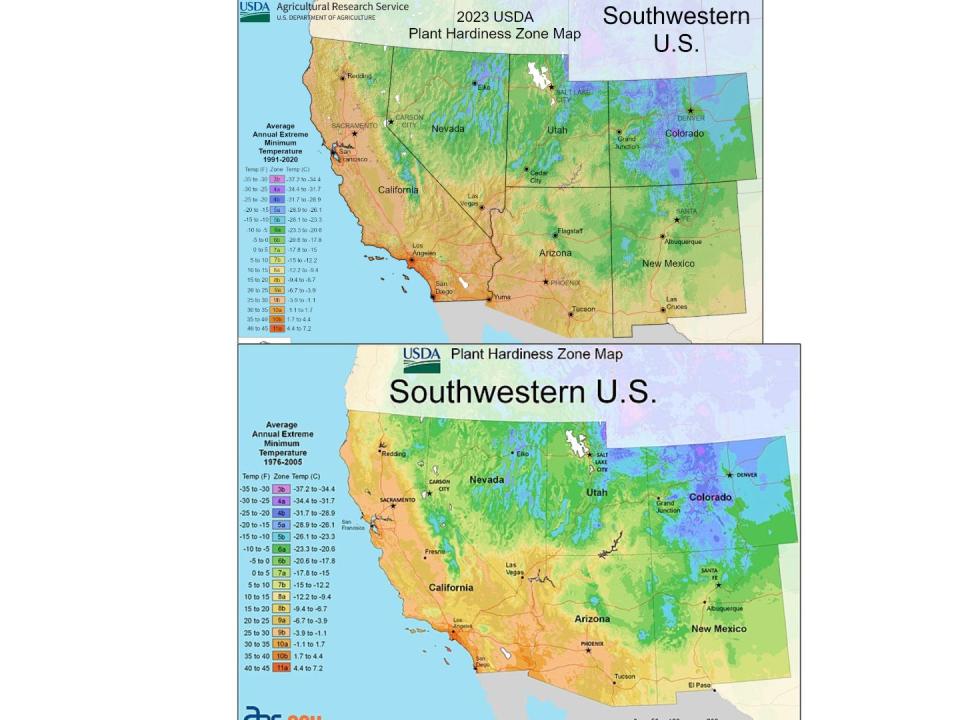

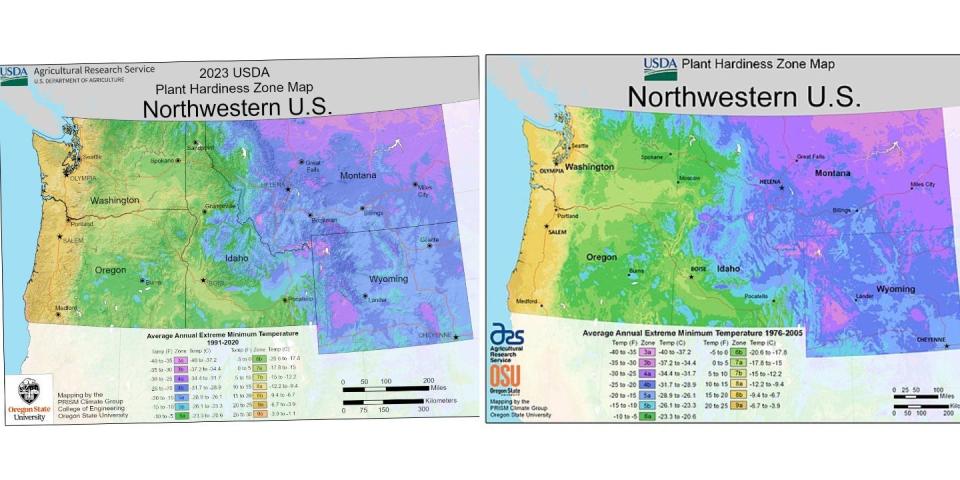

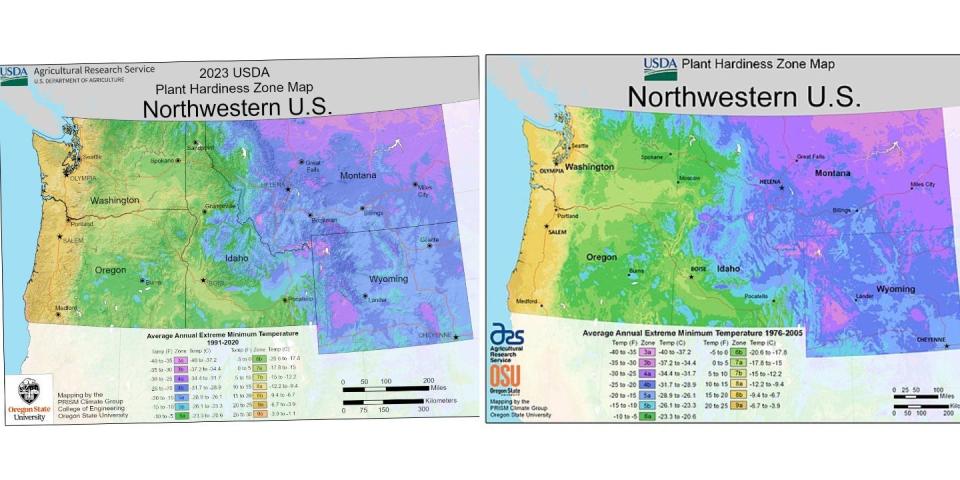

The USDA has updated its map of plant hardiness zones for the first time in more than a decade.

-

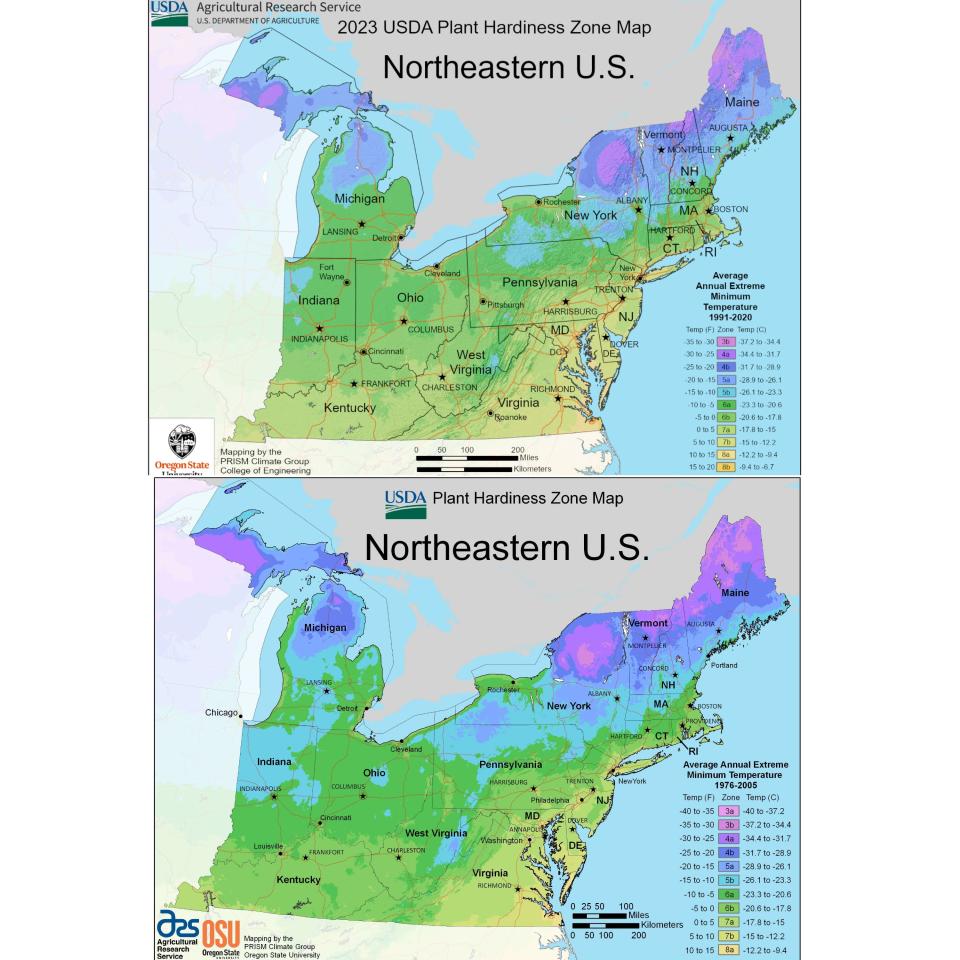

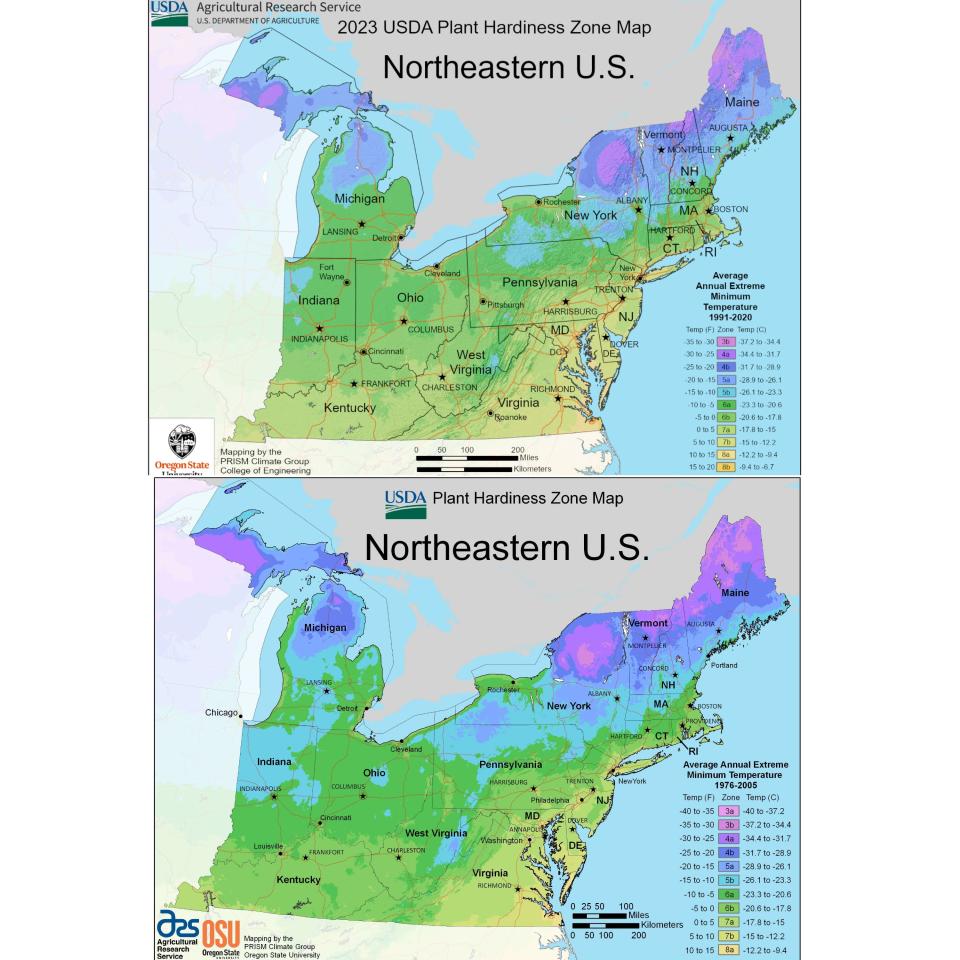

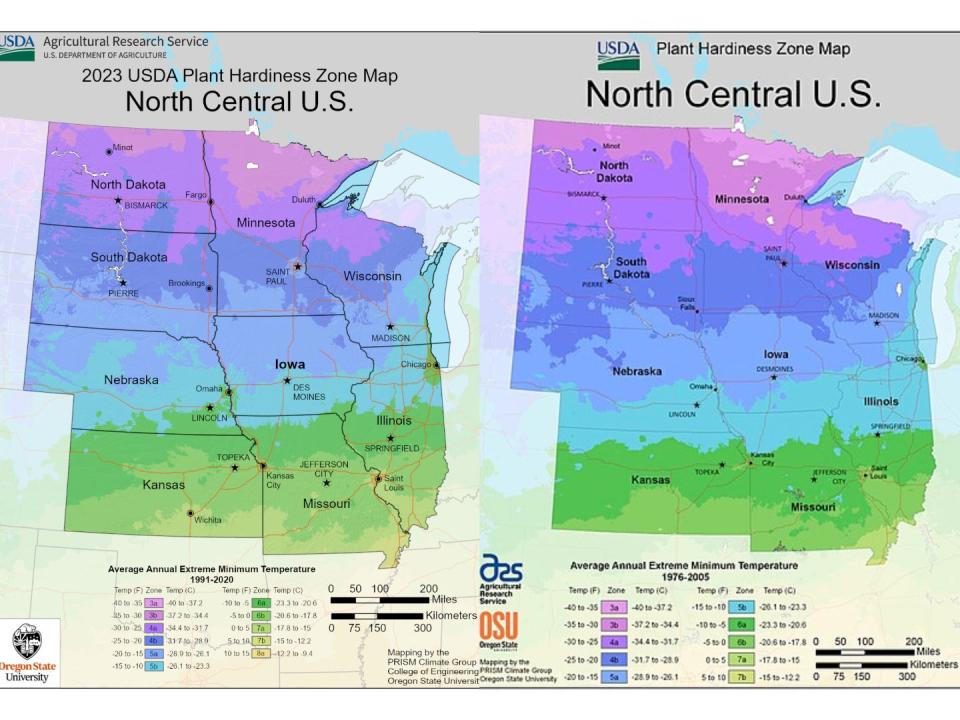

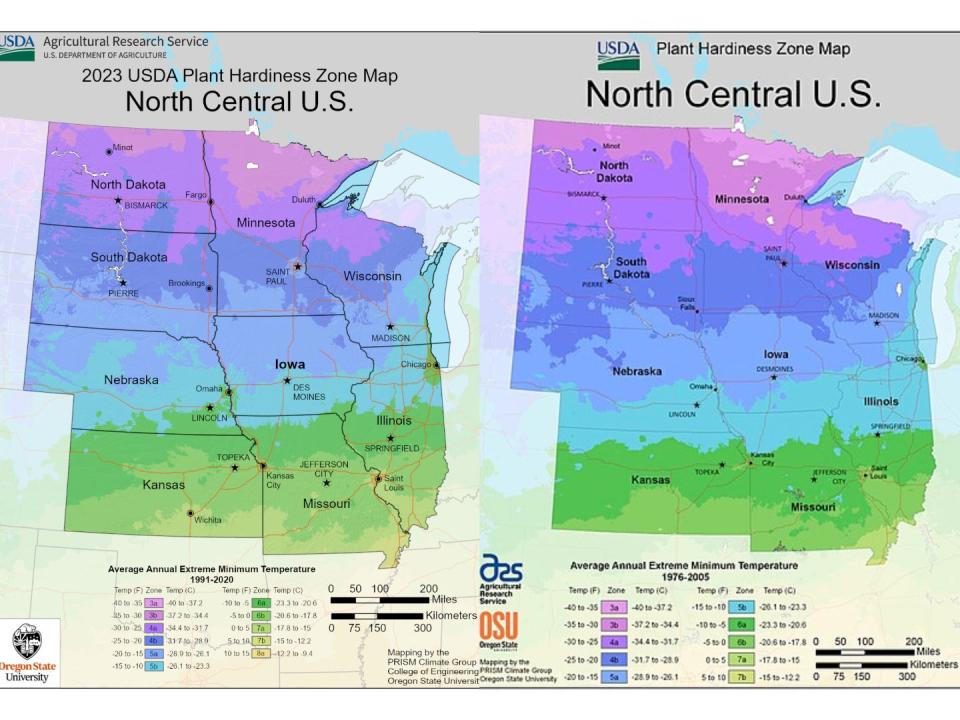

The new map shows that half the country has moved to warmer areas.

-

The updated zones could allow gardeners to grow plants they never could before.

The USDA has updated its plant hardiness zone map for the first time in more than 10 years. The new map could change how you garden.

Gardening consultant Megan London, for example, told NPR that she is now considering growing a variety of new cultivars including kumquats and mandarin oranges in her gardens in central Arkansas.

According to the new map, Central Arkansas has moved up half a zone from zone 7b to zone 8a since USDA last updated its map in 2012.

What are plant zones?

The USDA map is the national standard that lets gardeners and growers know what types of perennials—plants that return year after year—are most likely to thrive in certain locations. The map categorizes these sites by zones and hemizones, the USDA said on its website.

The US is divided into 13 growing zones. Each zone represents the lowest average winter temperature an area typically sees each year, according to the USDA.

Much of southern Florida, for example, is zone 10b (35 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit) and there are pockets of zone 3b (-35 to -30 degrees Fahrenheit) in northern Montana.

Many native plants in the United States are equipped to survive in a wide variety of zones, according to Better Homes & Gardens. Some ferns and grasses can thrive in zones 4 through 9, for example.

“This is all about the cold winter, this map,” said Chris Daly, director of the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University, to Business Insider. “It has nothing to do with planting zones in terms of when you plant or what can survive the summer.” He helped develop the map with the USDA.

Half of the US has moved to warmer plant zones

The new map for 2023 has pushed half of the country into a warmer hemisphere, while the rest of the country has remained in the same zone, the USDA said in a press release.

With the latest map update, some areas of Omaha, Nebraska after moving from 5b to 6a. This means that the lowest average winter temperature for that region rose from -15 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit to -10 to -5 degrees Fahrenheit.

When Kim Todd, professor and extension landscape specialist, came to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in Trinity Late 1970sthe area was zone 4. “We are now in zone 6a on this current map,” she said.

In the past several years, “we changed the average cold winter by 20 degrees,” she said. “That’s huge.”

As a result, some plants she used reliably as a landscape architect have problems with higher temperatures. “We’re looking at firs, for example, which are very similar to those colder zones really struggling with the winter heat and droughts, the winds, the drought,” Todd said.

On the other hand, non-native plants that died during Nebraska winters now have a chance to take hold. One example is Callery pears, which are fast growing and damage some grasses and other species. “For years, those ornamental pears produced no viable seed or any seed at all,” Todd said. That is now changing.

There are also implications for crops with the changing zones, Todd said. They include potentially longer growing seasons, earlier germination of weeds, and increased insect populations.

These changes may mean a change in what will grow best in your garden. But that doesn’t mean growers will have to look to non-native species, Todd said.

“We encourage people to look at indigenous people first,” Todd said. A good step is to look at the zone designations that nurseries and sellers put on seed packets or plant tags.

But, Todd said, local weather stations and university extension programs may give growers more targeted information about which plants work best in their microclimates. “An individual plan may or may not succeed in the wrong location,” Todd said.

Growers should also be wary of relying entirely on the belts, writes Jonathan Foster, a horticultural outreach professional, on the University of Maine’s Maine Gardner Manual site.

Boundaries on the new USDA plant zone map

“The map is a guideline, not a guarantee,” Foster wrote, and plants can thrive in some zones. However, you’ll want to consider other factors, such as summer temperatures and soil quality as well. The map does not show these nuances.

Foster also noted that more delicate plants, like poppies, as well as hardier trees and shrubs may not thrive in snowy climates like Maine.

The map is also limited in how detailed it can get, Daly said. Your garden may get more sun than your neighbors or there may be more shady spots due to trees. “They may have microclimates that are warmer or cooler than the zone says you are,” Daly said.

What caused half of the United States to move to a warmer area?

The USDA said the shift to warmer areas is not necessarily a reflection of global climate change, as several factors contributed to the changes.

Daly and the USDA used data from 1991 to 2020 and selected the coldest night of the year. “We only have 30 numbers that we’re averaging together,” Daly said. That’s why it’s important to look at decades of data, he said.

The temperature on the coldest night can change for a variety of reasons other than climate change. One year there may be no cold spell, and the next winter may be very severe, Daly said.

The new map is also based on information from thousands of other weather stations, according to the USDA. It pulled data from 13,412 weather stations compared to 7,983 for the 2012 map, according to a USDA press release.

Daly developed Prism, the software that created the map. “It is very good at reproducing the effects of features on the Earth’s surface, such as mountains, valleys, and coastlines, on climate patterns,” he said. It helped make the map more detailed and accurate than previous versions.

It is also interactive. “You can put in your zip code or you can click anywhere on the map and zoom and pan and see what your zone is,” Daly said.

How climate change is affecting plant hardiness zones

In the grand scheme of things, climate change is affecting where plants can grow, Daly said.

“We know for a fact that the average temperature is rising because of climate change. There’s no doubt about that,” Daly said. “And I think long-term that plant hardiness zones should gradually shift north.”

Todd said she hoped the zoning changes would not deter people from gardening or planting trees.

“This is not the first time we’ve seen a change in hardness or a change in climate or wind patterns or anything else, and it certainly won’t be the last,” she said. “The best approach we can have is to be the best stewards we can be.”

Read the original article on Business Insider