-

Scientists have offered a new explanation for the huge craters that can still be seen in Siberia.

-

These craters, first seen in 2012, can be more than 160 feet deep and over 65 feet wide.

-

They may be due to hot time bombs made of natural gas building up under the frozen ground.

Scientists are putting forward a new explanation for the giant exploding craters that appear randomly in the Siberian permafrost.

These craters, which were seen for the first time in 2012, are exciting scientists coming up in the frozen desert of Siberia.

They can be substantial, reaching more than 160 feet in depth and 65 feet in width, and blast debris hundreds of feet away.

Some reports have suggested that the explosions can be heard 60 miles away.

Now scientists are suggesting that hot natural gas seeping from underground reserves could be behind the explosive burst.

The results could explain why the craters are only visible in specific areas in Siberia.

The area is known for its large underground natural gas reserves, study lead author Helge Hellevang, who is a professor of environmental geosciences at the University of Oslo in Norway, told Business Insider.

“When climate change or atmospheric warming weakens the rest of the permafrost, then you get these eruptions – except in Siberia,” he said.

Gas fills the hole, but it comes from deep reserves

Permafrost traps a lot of organic matter. As the temperature rises, it melts, allowing that mulch to decompose. That process releases methane.

So the scientists naturally suggested that the methane coming from the permafrost itself was behind the craters.

This is not a crazy idea. The process in particular is thought to be the result of thermal karsts, lakes that appear in areas where permafrost is melting, which bubble with methane and can be ignited by fire.

But that doesn’t explain why the so-called explosion craters are so localized.

Only eight of these craters have been identified so far, all within a very specific area: the West Siberian Yamal and Len peninsulas in Northern Russia.

In contrast, blast lakes occur in a wide variety of areas where permafrost is found, including Canada.

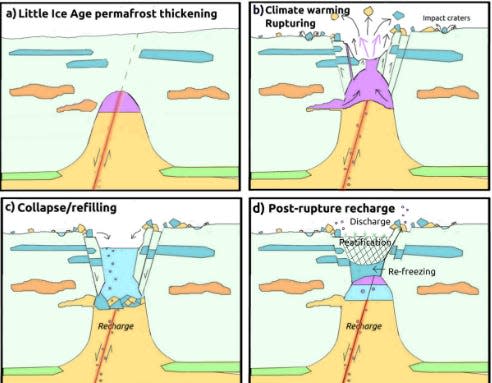

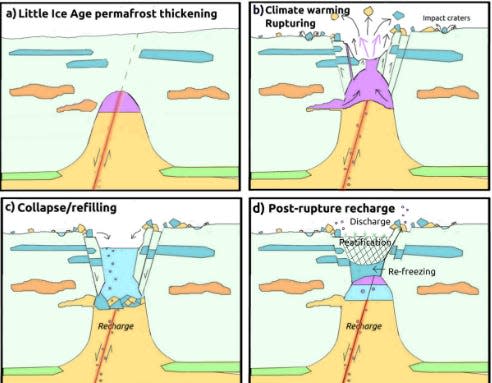

Helevang and his colleagues suggest that another mechanism is at work: hot natural gas, coming up through some kind of geological fault, is building up under the frozen layer of soil and warming the permafrost from below.

Those plumes of hot gas would help melt the permafrost from below, making it weaker and more likely to collapse.

“This eruption can only happen if the permafrost is thin and weak enough to break,” Hellenvang said.

Rising temperatures melt the upper layer of the permafrost at the same time. This creates the perfect conditions for a sudden release of the gas, which initiates an explosion or “mechanical collapse” of the pressurized gas.

That creates the crater, Hellevang and colleagues suggest.

The area is full of natural gas reserves, which is in line with the theory of Helevang and colleagues, according to the study.

“This area is one of the largest petroleum provinces in the world,” he said.

According to the scientist’s model, more of these craters could have formed and then disappeared as water and nearby soil fell in to fill the gap.

“This is a very remote area, so we don’t know the real number,” he said.

“If you look at the satellite image of the Yamal Peninsula, there are thousands of round plates like depressions. Most or all of them could be thermokarsts, but they could also be earlier craters was formed,” he said.

The hypothesis was published on the EarthArXiv online server last month. The article has not yet been validated by scientific peer review.

A dangerous hypothesis for the climate crisis

While the idea has merit, more evidence will be needed to show that these gas reserves are building beneath the permafrost, said Lauren Schurmeier, an Earth scientist at the University of Hawai’i who researches the topic. the New Scientist.

Still, if the hypothesis is found to be correct, this could spell trouble for climate models.

Natural gas is full of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. This could mean that the craters are acting as giant chimneys through which the harmful chemical could be suddenly released into the atmosphere, Thomas Birchall at the University Center in Svalbard, Norway, told the New Scientist.

“If that’s the standard way large accumulations fail, you’re dumping a lot of methane in a very short space of time,” he told New Scientist.

Hellenvang was cautious, however. If this phenomenon only exists in this very limited area, the impact on a global scale may be small. Although a large amount of methane is likely to be stored in underground reserves, it is not clear how much of this could be discovered.

“I think what we need to do is first understand how much methane is naturally leaking from these types of systems, and then compare that to how much methane is inside of the permafrost for organic matter,” Hellenvang said.

“Then we can have a more realistic budget for what can be released due to atmospheric warming or climate change,” he said.

Read the original article on Business Insider