Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

The historic Chandrayaan-3 mission, which made India the fourth country to land on the moon a year ago on Friday, revealed new evidence that supports a theory about the moon’s early history.

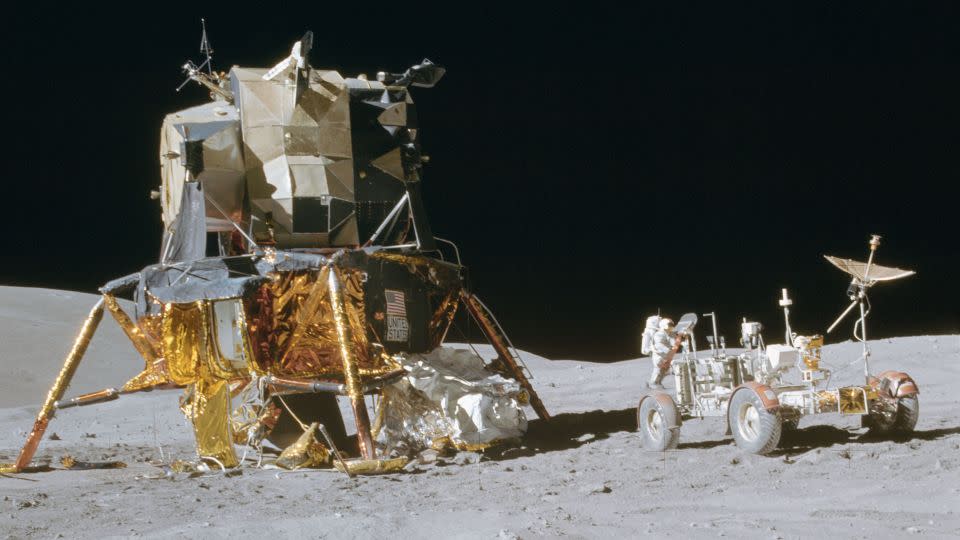

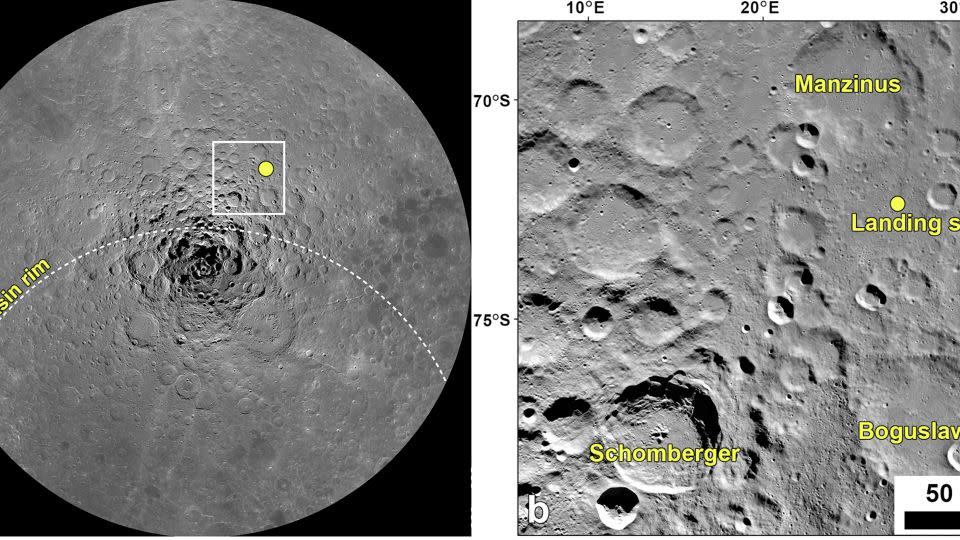

When the mission landed in the southern high latitude regions of the moon, near the moon’s south pole, it deployed a small six-wheeled rover called Pragyan, which means wisdom in Sanskrit. The rover was equipped with scientific instruments that allowed it to analyze particles within the lunar soil and measure the elements in it.

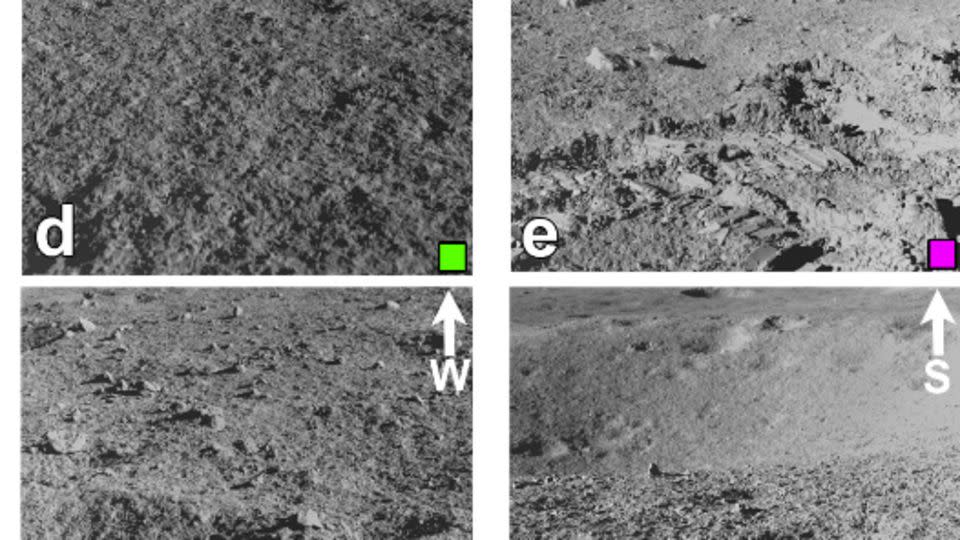

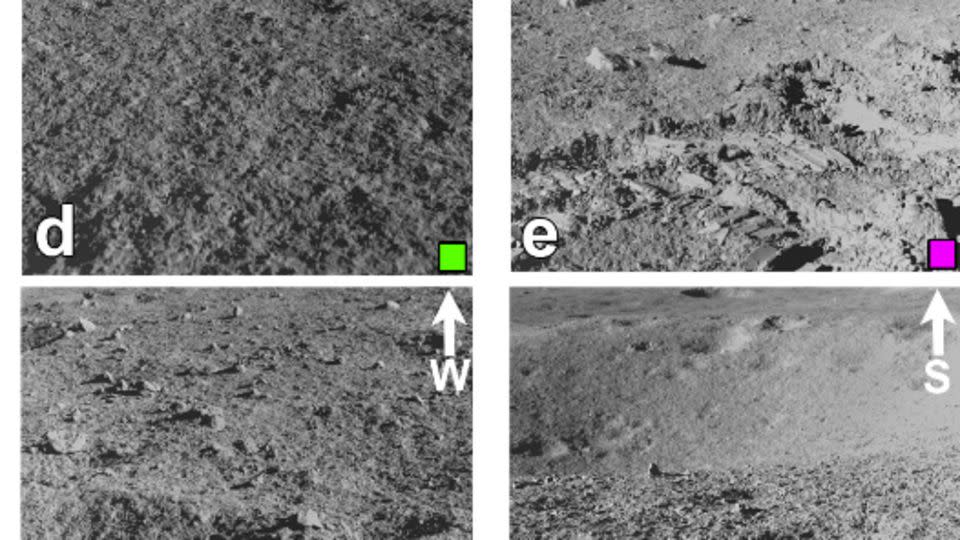

Pragyan made 23 measurements while rolling along a 338-foot (103-meter) region of the moon’s surface, located within 164 feet (50 meters) of the Chandrayaan-3 landing site, for about 10 days. The rover data detail the first measurements of elements within the lunar soil near the south polar region.

The rover found a relatively uniform composition made mostly of a rock called ferro anorthosite, which is similar to samples taken from the moon’s equatorial region during the Apollo 16 mission in 1972.

Researchers reported the findings in a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Lunar samples are helping scientists solve lingering mysteries about how the moon evolved over time, including how it formed during the solar system’s chaotic early days.

The presence of similar rocks in different parts of the moon lends further support to the decades-old hypothesis that the moon was once covered by an ancient magma ocean, the study authors said.

Ancient magma ocean

There are many theories about how the moon was formed, but scientists mostly agree that about 4.5 billion years ago a Mars-sized object or series of objects crashed into Earth and sent a lot of molten debris into space to to create the moon.

The first lunar samples collected during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969 led researchers to the theory that the moon was once a molten ball of magma.

The 842 pounds (382 kilograms) of lunar rocks and soil returned to Earth by the Apollo missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s fueled opinions that the moon was a celestial body caught in Earth’s gravity, or that the moon formed alongside the Earth from the same. debris. The rock samples showed that the moon was formed about 60 million years after the solar system began to form, according to NASA.

The magma ocean, probably hundreds to thousands of kilometers deep, existed for about 100 million years, the space agency says. As the magma ocean cooled, crystals formed within it.

Some rocks and minerals such as ferro anorthosite rose to the top to form the lunar crust and highlands, while other, denser, magnesium-rich minerals such as olivine sank deep below the surface into the mantle, said Noah Petro, both NASA project scientist for Lunar Exploration. Orbiter and Artemis III. Petro was not involved in the new study.

While the lunar crust has an average thickness of about 31 miles (50 kilometers), the underlying lunar mantle reaches a depth of about 838 miles (1,350 kilometers).

All the minerals and rocks on the moon have a story to tell about the history of the moon, Petro said.

When the rover Pragyan investigated the chemical composition of lunar soil, he found a mixture of ferro anorthosite and other types of rock, including minerals such as olivine.

The landing site of Chandrayaan-3, known as Shiv Shakti Point, was about 217 miles (350 kilometers) away from the edge of the South Pole-Aitken Basin, which is considered the oldest crater on the moon.

The research team believes that an asteroid impact created the basin about 4.2 billion to 4.3 billion years ago and found magnesium-rich minerals such as olivine, mixed in the lunar soil, said lead study author Santosh Vadawale, professor at the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad. , India.

The researchers are continuing to investigate the presence of these minerals that likely originated in the lunar mantle to provide more context for the origin and evolution of the moon, he said.

An ongoing lunar mystery

The mission proves why sending spacecraft to different lunar regions is critical to understanding the moon’s history, Vadawale said.

“All previous successful moon landings have been limited to equatorial to mid-latitude regions,” he said. “Chandrayaan-3 is the first mission to successfully land in the polar regions of the Moon and perform in-situ analysis. These new measurements in previously unexplored areas further increased confidence in the (lunar magma ocean) hypothesis.

After that, India’s lunar exploration program wants to explore the permanently shadowed regions of the lunar poles and bring back samples for detailed analysis in laboratories on Earth, Vadawale said.

Although erosion and the movement of tectonic plates have destroyed evidence of how Earth was formed, the moon is largely unchanged except for impact craters, Petro said.

“Every time we land on the surface of the moon, it provides that understanding of a specific moment, a specific location on the surface, which is very useful for testing all the models and hypotheses we have,” he said. . “That magma ocean hypothesis drives so many of our ideas about the moon, especially early in its history. The rover’s findings from the Chandrayaan-3 mission add another surface data point.”

Each mission not only adds another piece to the puzzle of understanding the moon but also provides insight into how Earth and other rocky planets like Mars formed. Scientists’ understanding of how the moon came to be drives their models of how all planets form and change, including planets outside our solar system, Petro said.

And as more missions are planned to return to the lunar surface, it’s like the gift that keeps on giving, especially with the prospect of collecting samples from different regions, including the far side of the moon and the poles.

“Every time we get a new piece of data,” Petro said, “that’s another great gift.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com