As another peach the color of Bellini’s sun begins to dissolve the stones and bricks of Venice into light and water, my position, hovering as regularly as I can on a black painted gondola, is missing one vital element on me – cheetah live with. diamond-studded collar.

If you think you don’t need a bejeweled jungle beast as a companion on board for a sunset gondola ride, then you probably don’t know the story of Luisa Casati.

Seventy-five years ago, Peggy Guggenheim arrived in Venice, along with her ever-growing collection of Surrealist and Modernist art. It was an assemblage described by the Tate in London, before being rejected by the Tate in London, as “non-art”.

Venice was more welcoming to Peggy in 1949 as she moved into a semi-deserted, unfinished life. palazzo on the banks of the Grand Canal named the Venier, after the Venetian family who ordered it to be built in 1752. A few years later, with their commercial success on the wane, the family abandoned the project and their palace to have reached only one storey in height.

Peggy’s unusual, and very licentious, life has been well described. But what interests me is the life of a former resident of the Venier palazzo (now known as the Guggenheim Collection), who lived in this truncated building a century ago.

Luisa Amman was the daughter of a cotton potentate from Milan and inherited the family fortune as a teenager when her parents died within two years of each other.

With money but no status, Luisa Marchese married Camillo Casati Stampa di Soncino in 1900. But the acquisition of her late parents’ newfound money and her husband’s old-time family reputation did not make for a happy marriage.

Choosing to ignore her only daughter Cristina, Luisa Casati kept her married name but spent less and less time in Italy, traveling first to Paris and then to Venice. She was, as her American journalist friend Natalie Clifford Barney wrote: “Always trying to escape from the inner alien through strange disguises”.

Walking around the Venier palazzo today, aka the Guggenheim Collection, with its faux-grass roof terrace, white-washed gallery walls and slick gift shop, it’s hard to imagine that this was once where gold Verdigris staircases and Murano glass chandeliers hung. alongside the holes i. the pockmarked roof and grime and ivy marred the outer walls.

However, within a year of Luisa’s purchase of this semi-ruined property, she had created gardens with mechanical songbirds in cages, classical statues filled in gold paint and a semi-feral menagerie of monkeys, sparrows, albino black loons (dyed in various colors) and peacocks. trained to sit on his windowsill.

Venice may have been in decline for a long time when it came to importing silk and spices. Material goods were replaced by pioneers of new philosophy and art that were being built La Serenissima.

Luisa was in danger all in the second decade of the 20th century, sailing on her private gondola with her pet lettuce and turning her palazzo into an art space where she entertained Picasso, Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, Nijinsky, Isadora Duncan and TE Lawrence.

Luisa was an extraordinary performer. Covered in nothing but a fur coat, she would walk naked through St. Mark’s Square with her (sedated) cheetah; a wonderful image that I can’t help but think is better than the student population and the huge clusters of cafes selling €20 cafes that all but swallow the loggias and basilica today.

I don’t spend long here before I decide to walk back to Luisa’s former home again and let myself imagine her hedonistic life here.

Approaching the canal, the steps were where visitors now take a break from gazing at the many Pollocks and Picassos in the Guggenheim, at a time when anyone wanted to attend a Casati-style party on the landing.

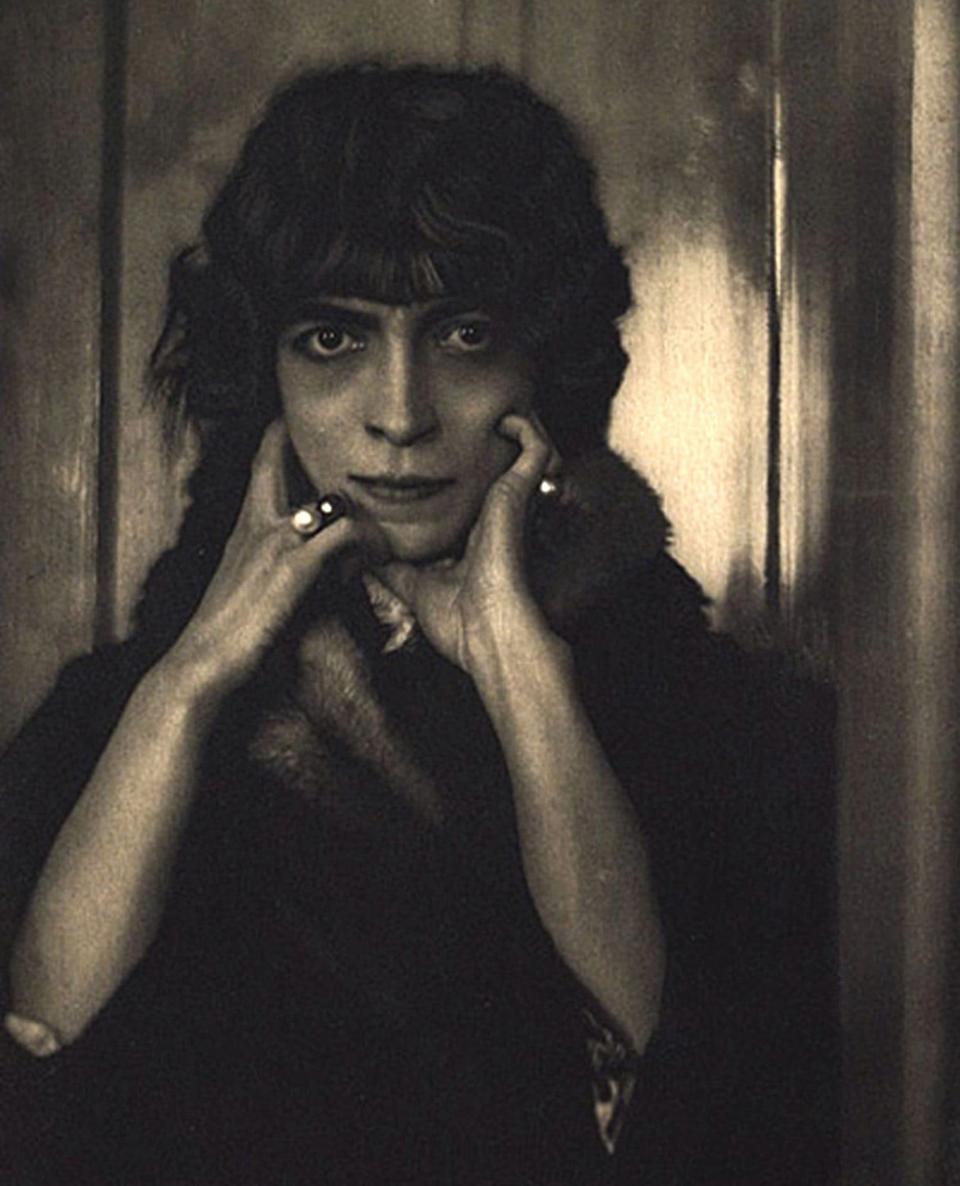

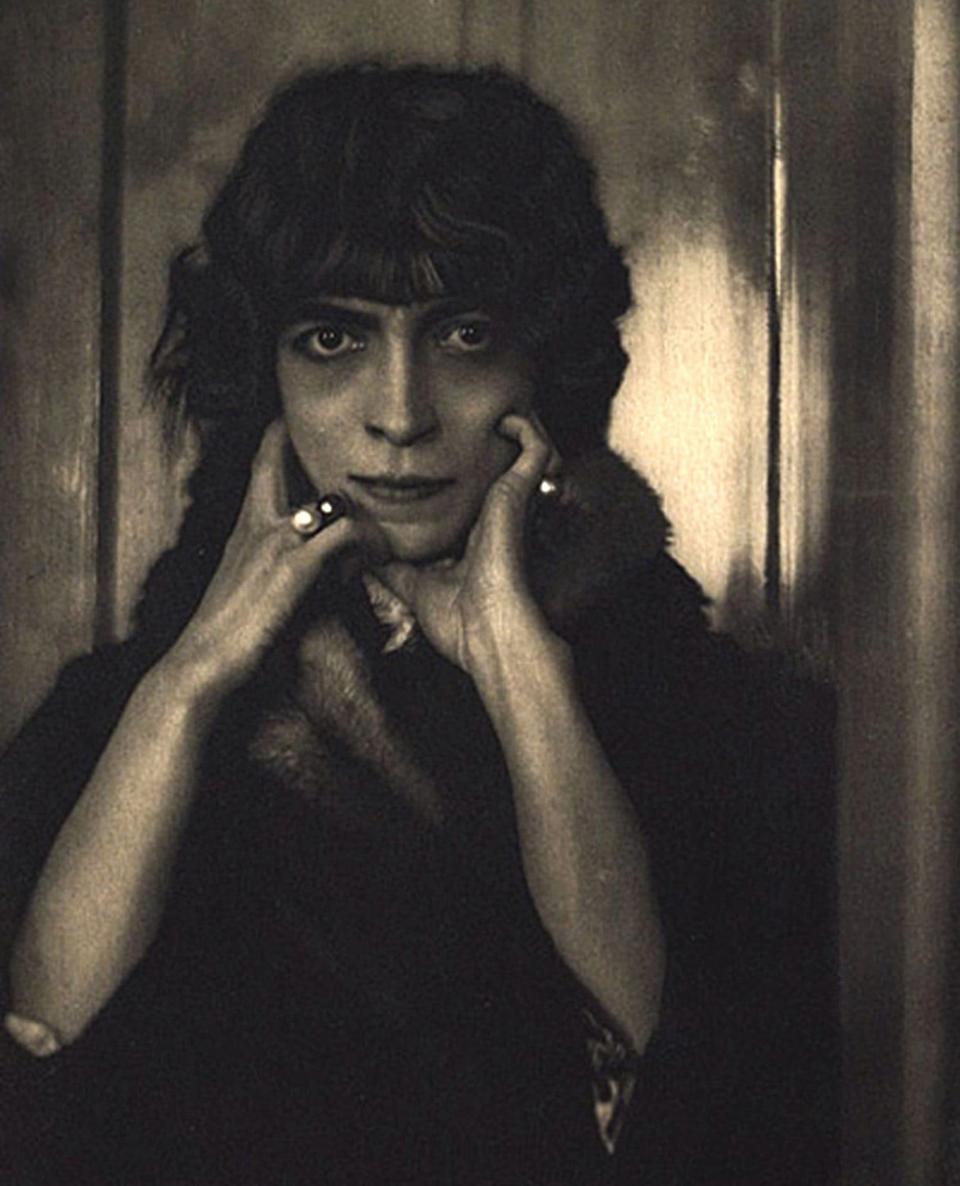

Clad in gold, silver brocade and pearls, at a time when non-actresses rarely wore make-up, Luisa drew black kohl and belladonna around her eyes and dusted her face with white powder.

Luisa’s balls, dressed variously, as a predator, sun goddess or Queen of the night, were rich with masks, wigs and crinolines. But, whatever hour the guests chose to meet at his palazzo, Luisa would be dressed with a corset of pearls, anomalous glitter, gold bangles, ancient lace chemises or chinchilla fur cloaks.

Wearing a costume based on St. Sebastian at one of her parties, Luisa’s dress was festooned with arrows that were fitted with light bulbs. She suffered a massive electric shock when it started to rain. At another party her egret feather dress moulted during the evening, leaving her almost completely exposed.

Perhaps the ultimate expression of the esthete credo, Luisa wanted her clothes, her house, her parties and her servants to be living, breathing works of art in their entirety, even to the point of saying that more than one of his servants died. having been completely painted in toxin-laced gold paint before one eastite.

The Casati coffers, however, were running dry. Living on a diet of cocaine, absinthe and opium, by 1930 Luisa was in debt that would be over $30m today. Sued by a coal merchant for non-payment of bills, she received a two-month suspended prison term. Selling the palazzo, she spent her last years in a tiny flat in Knightsbridge, surrounded by the stuffed remains of her dogs.

Luisa died in 1957, aged 76 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. But, after visiting her unclean grave in south-west London, I don’t think this woman, whose style has been checked by John Galliano and Alexander McQueen, could have been laid to rest anywhere but Venice.

Look carefully, as I did, at those lagoons and in the rooms of the Guggenheim, and Luisa’s angular, assertive shadow still lingers.

Basics

Rob Crossan was a guest of Tui, which offers three-night breaks in Venice, staying at the 4T Giorgionie Hotel, from £549 per person B&B based on two adults sharing a double room and including EasyJet flights from London Gatwick. A private 30-minute ‘Tui Collection’ Gondola ride costs £118 per person (tui.co.uk).