A prehistoric settlement known as Pompeii Peterborough was occupied for less than a year before it burned down, leaving behind a wealth of well-preserved artefacts, an archaeologist has said.

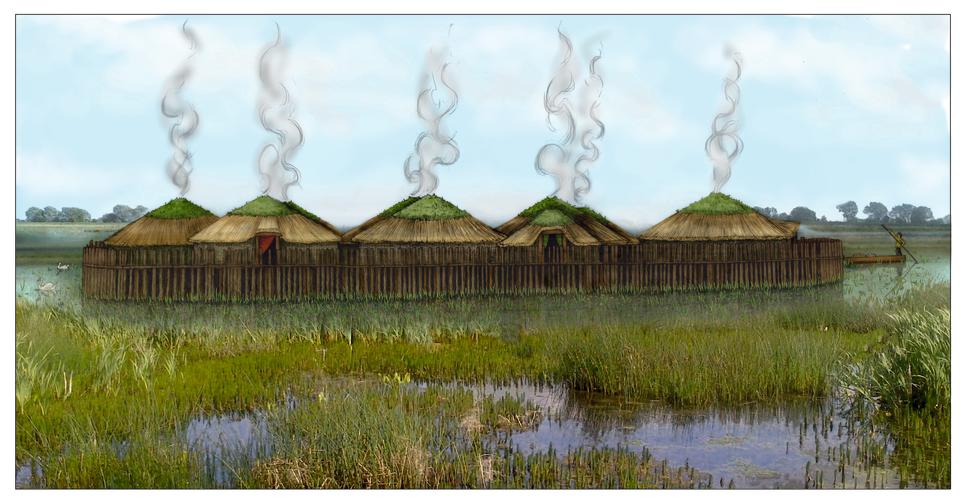

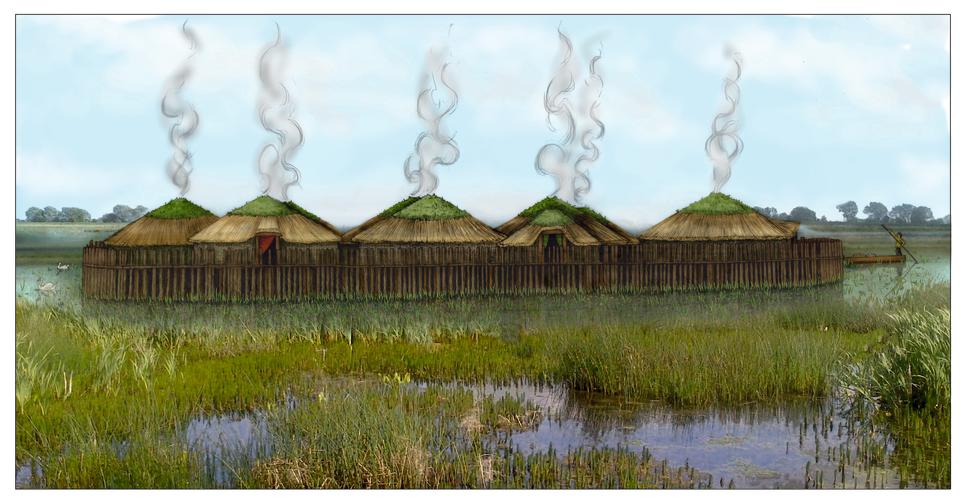

The Bronze Age house of around 10 circular wooden houses on stilts, overlooking the river, could have been inhabited by 50 to 60 people, said Chris Wakefield of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

The cause of the blaze in 850BC is unknown but may have been an attack or started accidentally and spread quickly between the closely packed houses, said Mr. Wakefield.

Remains of dwellings have been discovered at Must Farm Quarry in Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire in the East Anglian Fens and analysis provides an insight into normal life almost 3,000 years ago.

The excavation has drawn comparisons to the Roman city of Pompeii as it provides a “time capsule” into Bronze Age life just as the era was ending.

Environmental analysis has shown that the vegetation in the river helped to cushion the material that fell from the structures, thus preventing damage.

The items landed directly below where they were stored in the houses, giving the archaeologists a direct insight into how the exact houses were used.

Thousands of objects survived the mud and water, including nearly 200 wooden artifacts, more than 150 fiber and textile items, 128 pottery vessels and approximately 90 pieces of metalwork.

The details of the project are published in new books after extensive analysis.

Mr Wakefield said the site was believed to have been occupied for between nine months and a year before it was destroyed by fire.

He said the wood used to build the houses was “still green” and insects such as woodworm were absent.

People living and cooking in the circular houses threw rubbish from their doors, creating “rings around the structures”, Mr Wakefield said.

“We were able to separate the waste that was there from what was still in use inside the houses when they were burned,” he said.

“From that amount of material we were able to judge that this was a short settlement because there are not many bones of butchered animals from the time they were cooking, there are not many broken pots.”

He described what was left as “a wonderful time capsule of a site that was quite active when it was destroyed”.

“I think people have this perception that everyone was struggling to survive, that it was a terrible, bad time to be alive, and actually, when they look inside these structures it shows that there is a level of technology very sophisticated of them that do everything they need. to do,” said Mr Wakefield.

“They have axes that they’ve created a bit like a multi-tool that you can swap in different ax heads and use them very quickly for different applications.

“We have pots that are designed to be stacked inside each other, and this was long before the potter’s wheel was invented, these were all built by hand.”

He said there was a “bucket for recycling their metal in one of the houses”.

Researchers also looked at what people ate in the dwellings.

“We know they have these meaty stews that are thickened with wheat, which is a bit like a porridge consistency but very sweet,” Mr Wakefield said.

“They seem to be picking on certain parts of pork that they particularly like, so we’re getting a lot of forelegs coming back from the pigs.

“They could even flavor some of this stuff with spices, carrot and celery seeds too.”

More than 18,000 structural timbers were recorded and Mr Wakefield estimated there were nine or 10 houses, each containing a family or extended family.

“These are packed really tightly together buildings, they are far from touching their roofs,” he said.

“If a fire broke out in one of them it would easily spread through the other buildings and within a very short time the whole thing would have gone up in smoke and fallen down to that river.

“The other thing is that we know that the Bronze Age could be a violent period.

“We are finding things like spears and swords on this site and more widely, so it could be some sort of attack that caused the settlement to burn.

“The only thing that makes it more difficult is that nobody died during the fire so we don’t have any human remains found that were related to the fire itself.

“One of the things about archeology is that it’s often very difficult to get a definite answer to everything.

“The likelihood is that we won’t be able to say with certainty exactly why it was burned.”

He described the project as “one of the most comprehensive investigations of a prehistoric site ever undertaken in the UK”.

“It’s almost like pulling back the curtain and seeing what it would have been like that time ago,” he said.

“I’ve been digging for over 15 years and this project is the most incredible thing I’ve ever been involved with.

“This is the only site we’ve found, but there’s every indication that there are more of this kind of site hidden, buried underground out there in the Fens that we haven’t come across yet.”

Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, described the finds as “truly amazing”.

New books about the project, published by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, document the work and detail the discoveries made.

Some of the objects from the dig will be on display in an exhibition at Peterborough Museum and Gallery from 27 April.