Bourdon House, just a stone’s throw from Berkeley Square, could be in the middle of 21st-century Mayfair – tourists snapping selfies outside Louis Vuitton, and Annabel’s club pulling off its latest eye-catching display – but the mood here on a brisk winter morning. completely different. Beyond those glossy black doors – the ones that greeted the Duke of Westminster when he lived here – is a private members’ club so discreet he wouldn’t agree to reveal its fees, all plush burgundy interiors and the codes patrician dress. But the real action happens upstairs.

Unlike most tailoring emporia, whose studios are usually below street level, the center of Dunhill’s ordering and manufacturing operations is on the upper levels of Bourdon House. It’s a couple of modest rooms with canvas sheets dotted with the small print of every tailored jacket and pair of trousers on the rails, and a whiteboard charting the progress of each item through the system, and who it’s destined for – a sort of war sartorial. order. Its elevated position within Bourdon House means light streams into the bedrooms, ready for Dunhill’s new life under recently installed creative director Simon Holloway.

‘There is a sense of responsibility in looking after the heritage of a house like Dunall, and its future footprint,’ says Holloway. French conglomerate Richemont – which counts Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels and Alaïa as its crown jewels – bought Dunhill in 1998. Holloway, who cut his teeth at Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren, was across from historic British superintendent James Purdey & Sons. , too. owned by Richemont, in April 2023. ‘But I like to think Alfred Dunhill would approve of the direction we’re taking things,’ says Holloway, who replaced former creative director Mark Weston, and before John Ray, who was the head of Gucci before. menswear. It’s fair to say that there have been a few ups and downs over the past 15 years, but Holloway’s focus remains on Dunhill: focusing on the impeccable tailoring that the house is known for, best known for its suits and sports accessories. .

‘We’ve seen a significant rise in suit sales, and I think the pendulum is swinging back towards more tailored silhouettes from a fashion perspective. I think people are agitated to the point where they’re fed up with falling out,’ says Holloway. He first targeted the tailoring arm of the house, enlisting Savile Row secret weapon William Adams – a tailor who had worked at some of the best houses, including Ede & Ravenscroft and Kilgour – to head up the tailoring department. to pass and to fulfill Holloway’s vision of sophisticated, elevated suits.

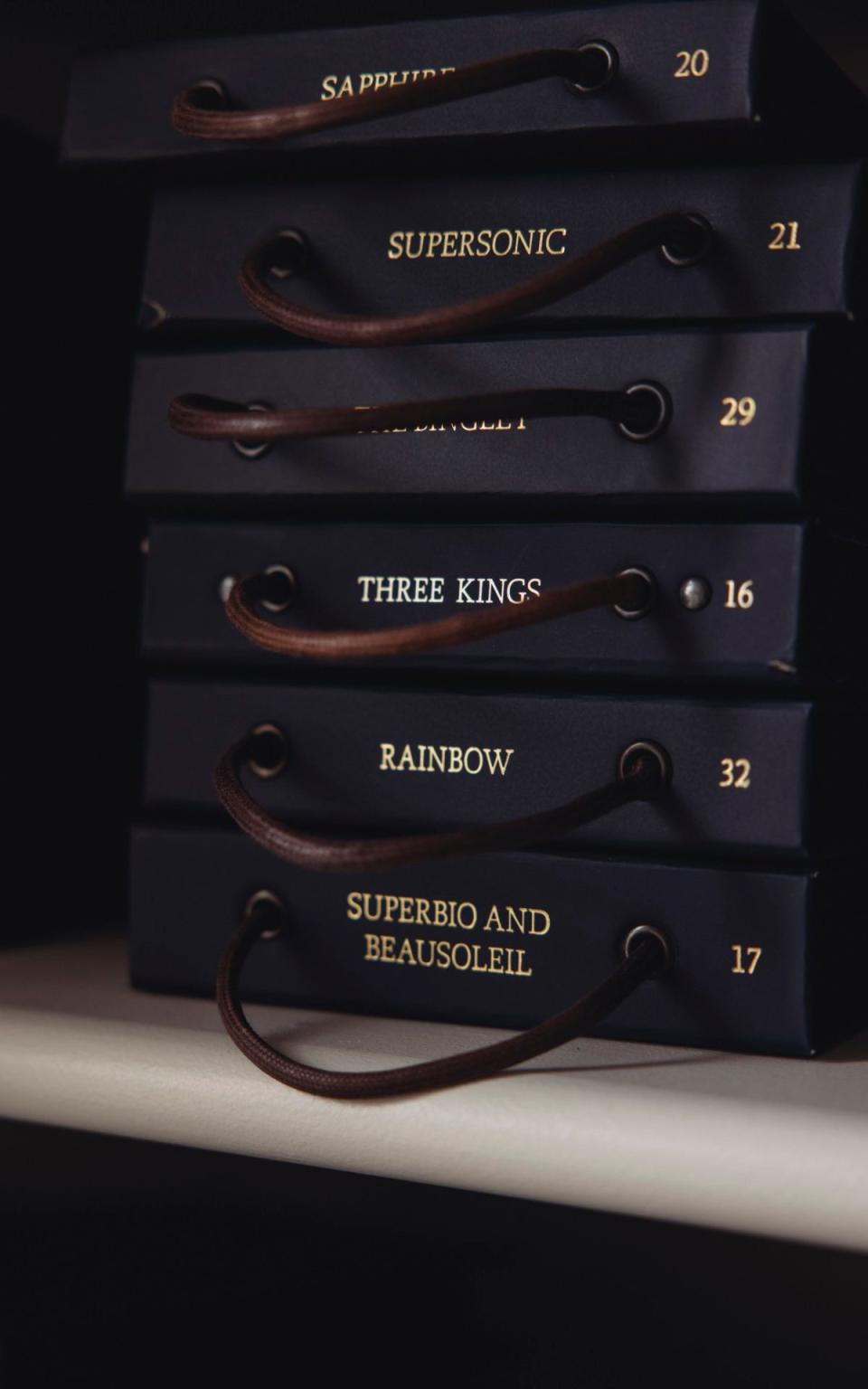

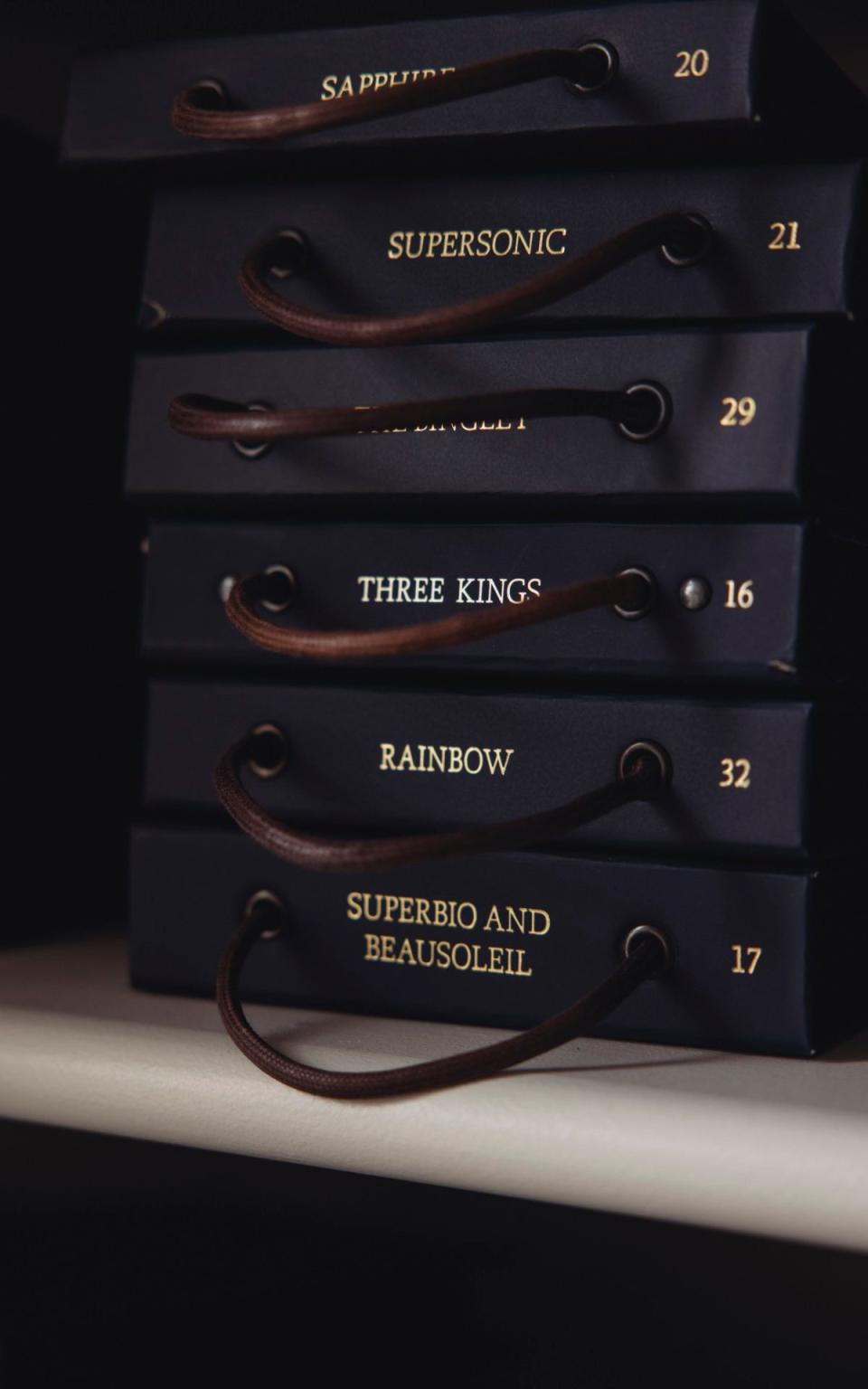

The nerve center of the House of Bourdon comprises three tailors, one trouser maker and two coat makers – the last term in the complex craft of suit jacket construction. The focus here is on manufacturing excellence. In the first place a client will sit down to consult one of the handsome rooms that open off the central staircase, and to spread fabric chips, especially those from British mills; Adams gestures to an inky expanse of navy pinstripes destined for a single-breasted suit. The process involves giving the team fabric, style and fitting minutes – anywhere from one to three meetings to fine-tune the details, although re-orders can be placed from anywhere in the world as long as which is measured at Dun Aill. Once the form and structure is decided – single or double breasted, dinner jacket or something more sporty – the whole process will take up to 10 weeks; costs depend on fabric choice and details, but expect a substantial four figures.

The most adventurous garment the custom studio has worked on so far was a fleece coat with a difference – the polyester fabric instead of cashmere, and the nylon accents with suede. As a rule, however, this is the place to come for exceptional bespoke suits for serious business events and meetings. They are working on up to 80 suits at any given time.

‘I wanted the impression that this is the pinnacle of British craftsmanship and a sense of craftsmanship and careful curation,’ says Holloway of his portrayal of Dunhill tailoring. Connoisseurs can spot signature style flourishes a mile away: Anderson & Sheppard’s soft drape, Edward Sexton’s peak lapels. What does Holloway have in mind for Dunhill? ‘It will be a masculine silhouette,’ he says. This will be welcome; after years of bloated, oversized shapes at Zegna and Versace, or reedy, gender-fluid cuts at houses like Celine and Saint Laurent, men’s suit proportions haven’t been in favor of the classic for a while. ‘Structure but with lightness, a very British look, and fabrics with a very English color palette and texture,’ says Holloway, who worked with historic yarn makers in Hawick, Scotland, to create unique garments. ‘The sense of Wales is at the heart of Dunall.’

Dun All, one of the few luxury houses born in Britain, was perhaps more than ever about innovation and doing things with pluck and hunger. Alfred Dunhill was a pioneering young man who started as an apprentice in his father’s saddlery business at the age of 15, and took the reins in 1893 at 21. As technology changed, so did he by ushering in the new world of cars, creating, as he called it, ‘everything but the motor’. A dashing young Bertie Wooster could see his Morgan in Dunhill leather, if Jeeves packed his white tie in his debonair knapsack and – in the roaring twenties – lit his cigarettes with a Dunhill lighter.

Either way, the Dunhill man has always cut a rather glamorous bow. Choosing something more racy over Savile Row required a Dunhill outfit to be actively chosen; sports jackets, driving accessories and finally a rakish array of evening wear. Fleming’s Bond was fond of his lighters, and Truman Capote presented him with a Dunhill black tie for his 1966 black and white ball.

Back in the eyrie above Bourdon House, the tailors are focused on the fuller details of the robe effect on the shoulder, or the alignment of the stripes on the label. ‘It’s important to try to thread a needle through one more century of Dunhill in this new era,’ says Holloway. The trusty outfit is a solid place to start.