By tracking the movements of billions of stars in our galaxy, the Gaia space telescope is unraveling the history of the Milky Way — and the spacecraft’s latest findings unravel that story more literally than ever.

Gaia has discovered two ancient streams of stars that appear to have merged more than 12 billion years ago, and less than 2 billion years after the Big Bang. The streams of stars are so old that they probably formed before the spiral arms or the expanding disk of the Milky Way even began to land.

These currents were named after the Hindu gods Shakti and Shiva, who came together to create the universe (or macrocosm). This is fitting because these ancient stellar streams probably coalesced to form the galaxy in which we live.

Related: Scientists reveal never-before-seen map of Milky Way’s central engine (image)

“What is truly amazing is that we can detect these ancient structures at all,” Khyati Malhan, research team leader and Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) scientist, said in a statement. “The Milky Way has changed so much since the birth of these stars that we wouldn’t expect them to be so clearly identified as a group – but the unprecedented data we’re getting from Gaia has.”

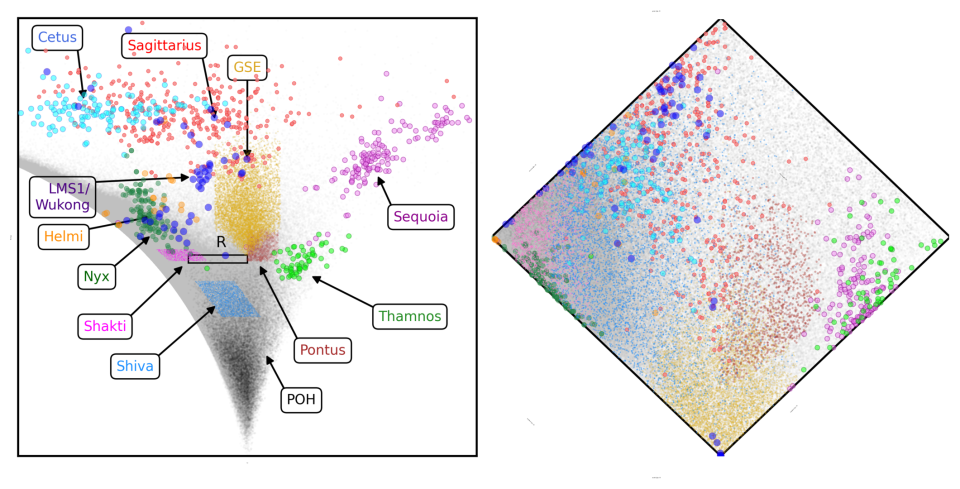

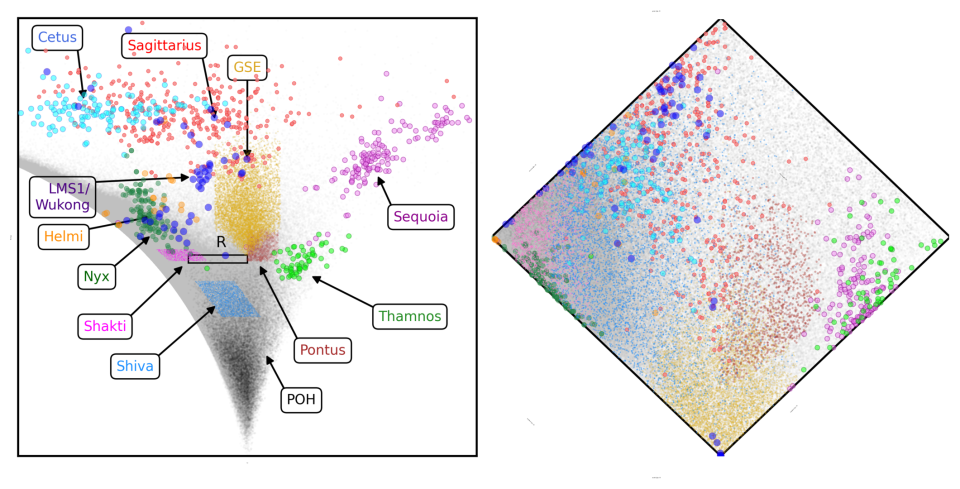

The Gaia observations allowed Malhan and colleagues to determine the orbits of individual stars in the Milky Way as well as their compositions.

“When we looked at the orbits of all these stars, two new structures stood out from the rest among stars of a certain chemical composition,” continued Malhan. “We named them Shakti and Shiva.”

Shakti and Shiva, threads of the cloth of the Milky Way

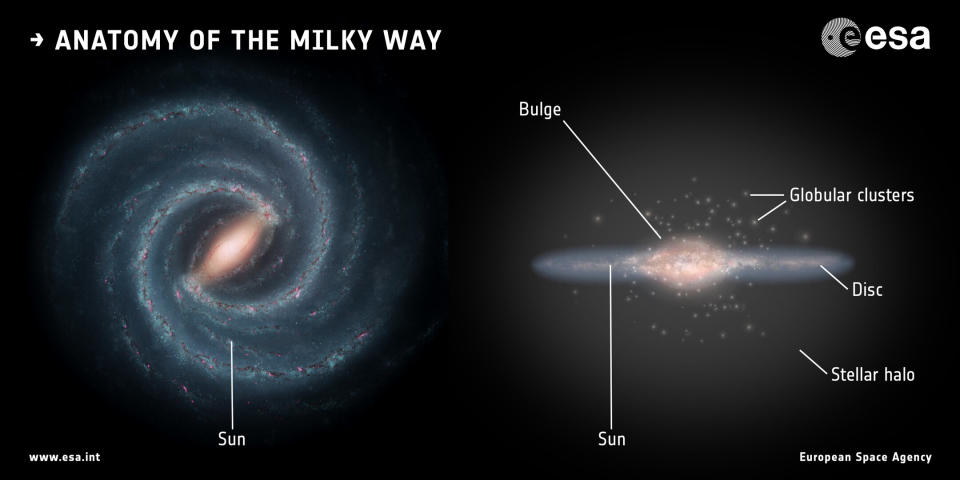

In 2022, Gaia studied the inner region of the Milky Way, finding that it was filled with the oldest stars in our galaxy. Continuing this Galactic archeology project, the new study has now revealed how these ancient stars were distributed, marking them out as separate fragments that merged with the infant Milky Way long before it took form. spiral galaxy.

As we see them today, both Shakti and Shiva are known as “protogalactic fragments” near the center of the Milky Way; they both have similar orbits around that central region. Each stream has a mass of about 10 million suns, and the stars that form this mass are estimated to be between 12 billion and 13 billion years old.

Throughout their lives, stars conduct nuclear fusion in their cores, converting hydrogen into helium and fusing helium into heavier elements, which astronomers call metals. The first generation of stars were born when the universe was mostly hydrogen and helium, so they lacked such metals in large concentrations.

When this first generation of stars died and exploded in a supernova, however, they scattered the elements they were creating throughout the cosmos. These metals would eventually be found in the second generation of stars, which were therefore richer in metals than the first generation. This process of a star’s life, death and rebirth has continued, and means that astronomers can age stars based on observed metal content.

“The stars in the core of our galaxy are metal-poor, so we called this region the ‘poor old heart’ of the Milky Way,” said research co-author Hans-Walter Rix, who was a “galactic archaeologist” in charge of also work in 2022. in the statement. “Until now, we have only identified these very early fragments that came together to form the ancient core of the Milky Way.

“With Shakti and Shiva, we now see the first pieces that are comparably old but located further out. These represent the first stages of our galaxy’s growth towards its current size.”

Although there are many similarities between Shakti and Shiva, there are some important differences between the two ancient star streams. The team found that the stars that make up Shakti are further from the center of the Milky Way, for example, and have more circular orbits than Shiva’s stars.

Related Stories:

— A new map of the Milky Way reveals the amazing mess of our galaxy

— The Milky Way galaxy could have a different shape than we thought

— How do we know what the Milky Way looks like?

More than 12 billion years ago, the Milky Way would have been composed of many long, irregular filaments of gas and dust that coalesced, forming stars and engulfing each other to eventually give birth to our galaxy.

Thanks to Gaia, astronomers now know that Shakti and Shiva were involved in this early mixing of the Milky Way. However, this does not answer all the pressing questions about our infant galaxy – and researchers will continue to use Gaia to build an excellent family tree of the Milky Way.

“One of the goals of Gaia is to reveal more about the beginning of our galaxy, and it is certainly being achieved,” said Timo Prusti, Project Scientist for Gaia at the European Space Agency (ESA). “We need to pinpoint the subtle yet crucial differences between the stars in the Milky Way to understand how our galaxy formed and evolved. This requires incredibly precise data – and now, thanks to with Gaia, we have that data.

“As we discover surprising parts of our galaxy like the Shiva and Shakti currents, we are filling in the gaps and painting a more complete picture of not only our current home but our earliest cosmic history.”

The team’s research was published on March 21 in the Astrophysical Journal.