Star Wars fans will definitely get a kick out of binary star systems known as “Tatooine” systems – a reference to the planet Luke Skywalker stands on to look at two suns in Star Wars: A New Hope. As it turns out, some of the planets in real-life versions of these systems may have been getting a much more literal kick out of them, too.

New research suggests that “rogue planets” that stray into the Milky Way – i.e., planets cut off from their parent stars and living as cosmic orphans – may be getting kicked out of binary star systems, or binary systems. But there’s a twist (literally)!

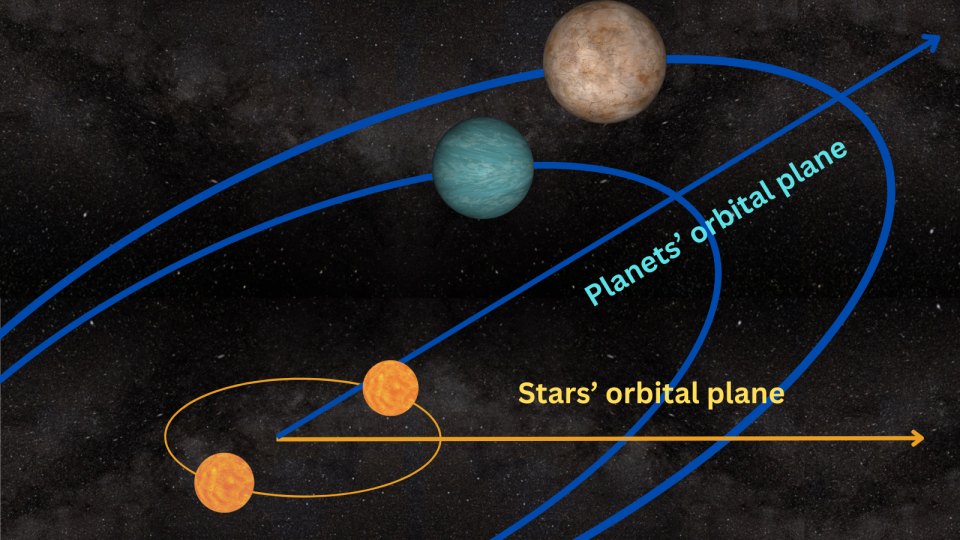

The team found that rogue planets are more likely to be released from specifically “Tatooine twisted” systems. These are systems where the stars and planets orbiting them are misaligned, so they exist at skewed angles from each other.

As telescopes have improved, the detection of these rogue planets has increased to the point that astronomers think that there are free-floating planetary bodies much larger than stars in cozy, solar system-like arrangements in the Milky Way. . Recent projects put the number of rogue planets ejected from their home systems in our galaxy as high as a quarter trillion (10 followed by 14 zeros). These new and potentially complicated results for Tatúnán may help explain why rogue planets are so common.

Related: NASA’s TESS exoplanet hunter may have spotted its 1st rogue planet

“A normal planetary system, like our solar system, consists of multiple planets orbiting a single star. On the other hand, binary stars are also common, accounting for more than 50% of star systems,” Cheng Chen, team leader and the. an astrophysicist at the University of Leeds, said Space.com. “If there are planets orbiting a binary, we call it a ‘planetary system.’

While we know that planet formation is a byproduct of star formation, we still don’t know the rates of planet production. That’s because we can’t be sure how much is being ejected from their systems and roaming the galaxy as icy bodies that are hard to spot. These would be bodies that are not lit or heated by a parent star.

“More accurate rogue demographic determinations can help us complete the last piece of the planet formation puzzle,” Chen said.

He went on to explain that the orbits of some of these planets may not be aligned with the orbits of their host binary stars. Astronomers call these “tilted curtain planets”, and investigating them could reveal the dominant mechanism for generating free-floating planets.

Kicked out of their cosmic homes

Scientists believe that orphan planets form around infant stars just as planets that remain “tethered” to their stellar parent do. Stars are essentially born from a collapsing cloud of gas and dust, but this process does not consume all the material in that cloud, leaving the stars surrounded by “protoplanetary disks.” Over-dense regions of these discs collapse and form planets. About 4.6 billion years ago, that is what gave rise to the solar system and its planets, including Earth.

The period after planet formation is believed to be extremely chaotic for these young systems, making “messy” gravitational interactions possible. let out planets.

In fact, researchers theorize that our solar system may have had a fifth giant planet at Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune during a chaotic period known as “late instability.” The idea is that this “extra” planet was moved from its orbit, then gravitational interactions with the other giant planets would have expelled the unfortunate planet from the entire solar system.

However, Chen and his team did not focus on a relatively simple single-star system like the solar system to investigate the origin of rogue planets. Instead, they focused on more complex binary star systems, like the one seen in that iconic sunset over Tatooine.

“Three or more body problems are much more complicated than two-body problems. The inner stellar binary can affect the planet due to dynamical effects,” said Chen. “On the other hand, planet-planet interactions can also affect a planet’s orbit.”

The team simulated planetary systems in which two planets are separated by some distance from their stars and follow orbits that are tilted relative to the orbit of the central binary star.

Chen and his colleagues experimented with different systems with a range of orbital inclinations and a range of planetary separations. They also tinkered with the mass of the planets involved and still kept one planet larger than the other.

“ have found that a giant planet like Jupiter can interfere with other smaller planets around the binary and expel them from the system. This can happen when two planets are close or when they are located around orbital resonance regions,” said Chen.

The Leeds University researcher also explained that the team’s previous study found that two Jupiter-sized planets around one star could become unstable when their separation is very small, less than twice the distance between Earth and the sun. In this study, however, they found that a single tilted giant planet around a binary could cause small planet ejections even when their separations are wider.

This surprised Chen and his colleagues, as it showed that a more diverse range of planets could be expelled from the complex Tatooine systems than previously thought.

“At first, we thought that only two giant planets around the binary could be expelled because of the strong dynamical effects between the two planets and the planet-binary interactions,” said Chen. “We didn’t expect that small planets could be expelled so efficiently. As a result, curtain systems could produce rogue planets from small to large.”

“Small planets are more common than high-mass planets,” he continued. “Therefore, these systems could add to the population of rogue planets in the universe.”

This means that the systems the team investigated could account for the predicted abundance of Earth-sized rogue planets.

RELATED STORIES:

— A ‘trapped’ alien planet could be hiding on the edge of our solar system — and it’s not ‘Planet X’

— 400 Earth-sized rogue planets could be roaming the Milky Way

— A cosmic ‘fossil record’ could be hidden among the orphan stars

Chen explained that the team is looking for other mechanisms that could also produce rogue planets. This includes the possibility that other stars could fly through planetary systems and cause gravitational disturbances that could lead to the expulsion of a planet. This could be a relatively efficient way to produce rogue planets, whether from a single star or a binary system.

Chen is unlikely to give up his investigation of rogue planets. This means that the efforts of the astrologer from Taiwan could help to bring these cosmic orphans safely from their stars “in from the cold” – figuratively at least.

“I like planets! When I was 8 years old, I decided to be an astronomer and studied all nine planets in our solar system before Mike Brown changed that by reclassifying Pluto,” joked Chen. “However, today, more than 10,000 exoplanets have been discovered, which show unexpected characteristics for us to study. Rogue planets are not alone; we should not let them become orphans but considered as members of our planetary family.”

The team’s research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.