-

A space elevator could make it much cheaper and faster to get goods to other planets, like Mars.

-

The Japan-based Obayashi Corporation announced plans in 2012 to begin building one by next year.

-

Not only would it cost $100 billion, there are huge technological and organizational challenges.

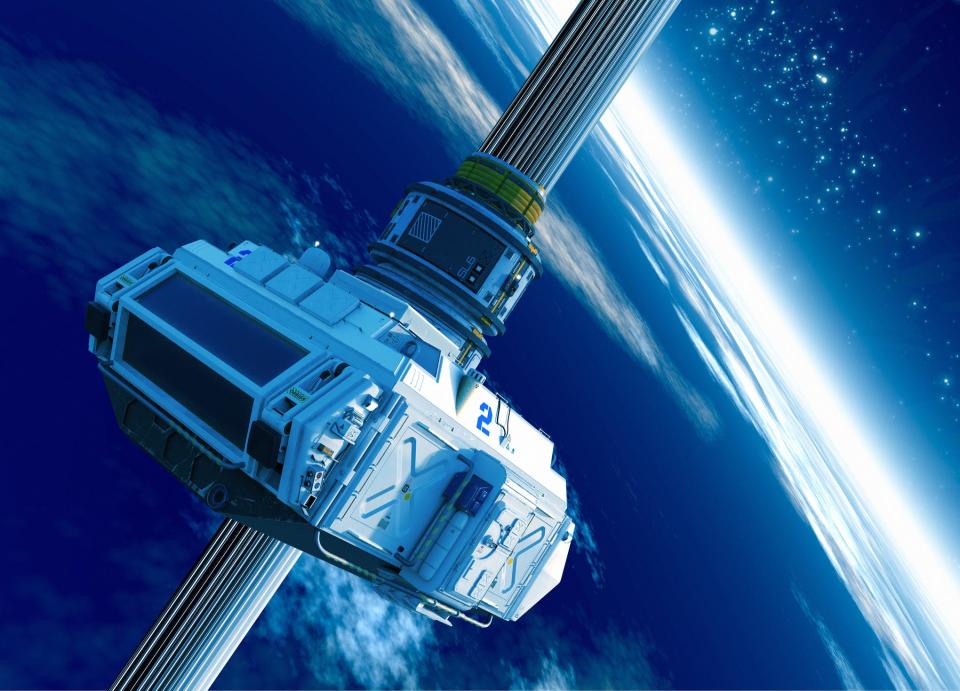

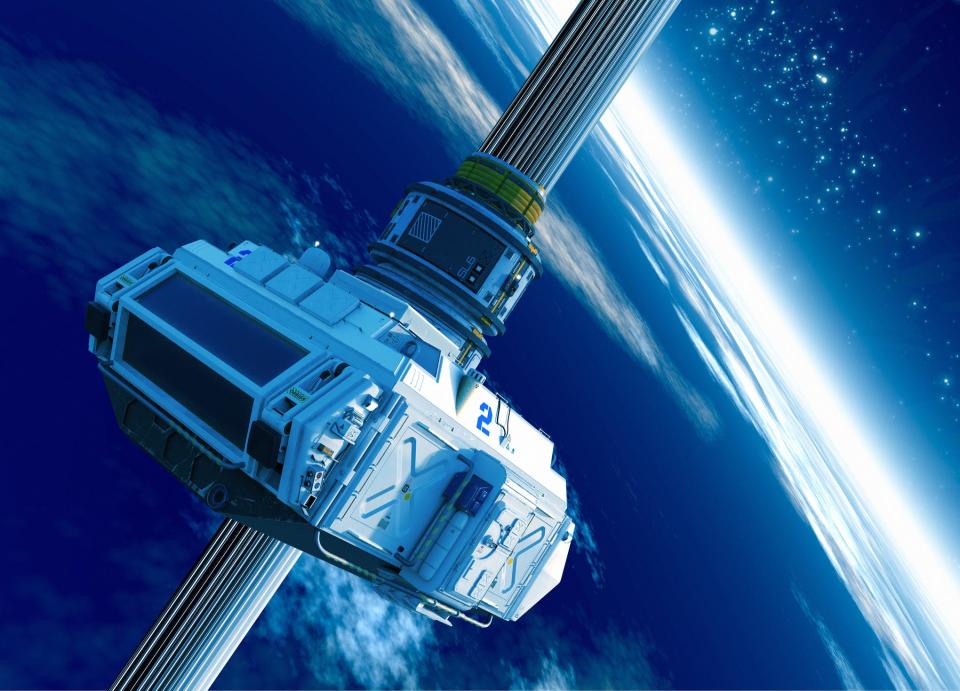

Imagine a long string connecting Earth to space that could send us into orbit at a fraction of the cost and sling us to another world at a higher speed.

That’s the basic idea behind a space elevator.

Instead of taking six to eight months to reach Mars, scientists have estimated that a space elevator could get us there in three to four months or even as fast as 40 days.

The concept of space elevators is not new, but engineering such a structure would not be easy, and there are many other issues besides technology in the way.

That’s why the ambition to build one has been taken seriously recently.

The company Obayashi Corporation based in Japan thinks it has the expertise.

Japan aims to build a space elevator by 2050

Known for building the world’s tallest tower, the Tokyo Skytree, Obayashi Corporation announced in 2012 that it would reach even greater heights with its own space elevator.

In a report that same year, the company said construction on the $100-billion project would begin by 2025 and could begin operations as early as 2050.

We checked in with Yoji Ishikawa, who wrote the report and is part of the company’s future technology creation department, to see how the project is progressing ahead of 2025.

While Ishikawa said the company likely won’t start construction next year, it is currently “engaged in research and development, rough design, partner building and promotion,” he told Business Insider.

Some doubt that such a structure is even possible.

“It was a kooky idea,” said Christian Johnson, who published a report on space elevators last year in the peer-reviewed Journal of Science Policy & Governance.

“That said, there are some people who are real scientists who are really on board with this and really want to do it,” Johnson said.

A cheaper way to space

Sending people and things into space on rockets is extremely expensive. For example, NASA has estimated that its four Artemis lunar missions will cost $4.1 billion per address.

The reason is something called the rocket equation. It takes a lot of fuel to get to space, but the fuel is heavy, which increases the amount of fuel you need. “And so you kind of see a vicious cycle there,” Johnson said.

With a space elevator, you don’t need rockets or fuel.

According to some designs, space elevators would send cargo into orbit on electromagnetic vehicles called climbers. These climbers could be powered remotely – like by solar or microwave power – eliminating the need for fuel on board.

In his report to the Obayashi Corporation, Ishikawa wrote that this type of space elevator could help reduce the cost of moving goods into space to $57 per pound. Other estimates for space elevators in general put the price at $227 per pound.

Even SpaceX’s Falcon 9, which, at about $1,227 a pound, is one of the cheaper rockets to launch, is still about five times as expensive as the higher cost estimates for space elevators.

There are benefits other than cost, too.

There is no danger of a rocket exploding, and the climbers could be zero-emission vehicles, Johnson said. At a relatively leisurely speed of 124 miles per hour, the Obayashi Corporation’s climbers would travel slower than rockets with less vibration, which is good for sensitive equipment.

Ishikawa said the Obayashi Corporation sees a space elevator as a new type of public works project that would benefit all of humanity.

There is not enough steel on Earth to make a space elevator

Currently, one of the biggest obstacles in building a space elevator is removing the string or tube.

To withstand the enormous tension, the tube would have to be very thick if it were made of ordinary materials, such as steel. However, “if you try to build it out of steel, you’d need more steel than there is on Earth,” Johnson said.

Ishikawa’s report suggested that Obayshi Corporation could use carbon nanotubes. Nanofiber is a rolled-up layer of graphite, the material used in pencils.

It’s much lighter and less likely to break under stress than steel, so the space elevator could be much smaller, Johnson said. But there is a catch.

Although nanotubes are very strong, they are so tiny, a billionth of a meter in diameter. And researchers are not very long on them. The longest is only about 2 feet.

To be properly balanced and still achieve a geosynchronous orbit — where objects stay in sync with Earth’s rotation — the string would have to be at least 22,000 miles long, according to Ishikawa’s report.

“So we’re not there,” Johnson said of the length of the nanotubes. “But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”

Instead, researchers may have to develop an entirely new material, Ishikawa said.

Other obstacles

Whatever the matter turns out to be, there are still other problems.

For example, the space elevator would be under such incredible stress that it would likely collapse, Johnson said. A lightning strike could vaporize it. There are also other weather to consider such as tornadoes, monsoons, and hurricanes.

Locating the base at the equator would reduce the likelihood of a hurricane, but would still have to be in the open ocean to make it harder for terrorists to target, Johnson said.

It would also take a lot of trips to make up for that huge price tag for construction.

That’s just scratching the surface of the challenges. And one company can’t solve them all, Ishikawa said. “We need partnerships,” he said. “We need different industries.”

“Of course,” said Ishikawa, “it is very necessary to raise funds.”

That’s a lot of hurdles to overcome to start construction in time for operation by 2050, especially since Ishikawa estimated it would take 25 years to build. He noted that the 2050 estimate always came with caveats about technological advances. “It’s not our goal or our promise,” he said, but the company is still targeting that date.

“I think those time estimates are optimistic,” Johnson said, “even assuming that tomorrow was fate.”

Read the original article on Business Insider