-

Saudi Arabia has begun its ambitious project to build a city in the shape of a line.

-

Although the concept of linear urban design has existed since the 19th century, few have attempted it.

-

Business Insider asked architects, urban planners, and academics whether a line is a good shape for a city.

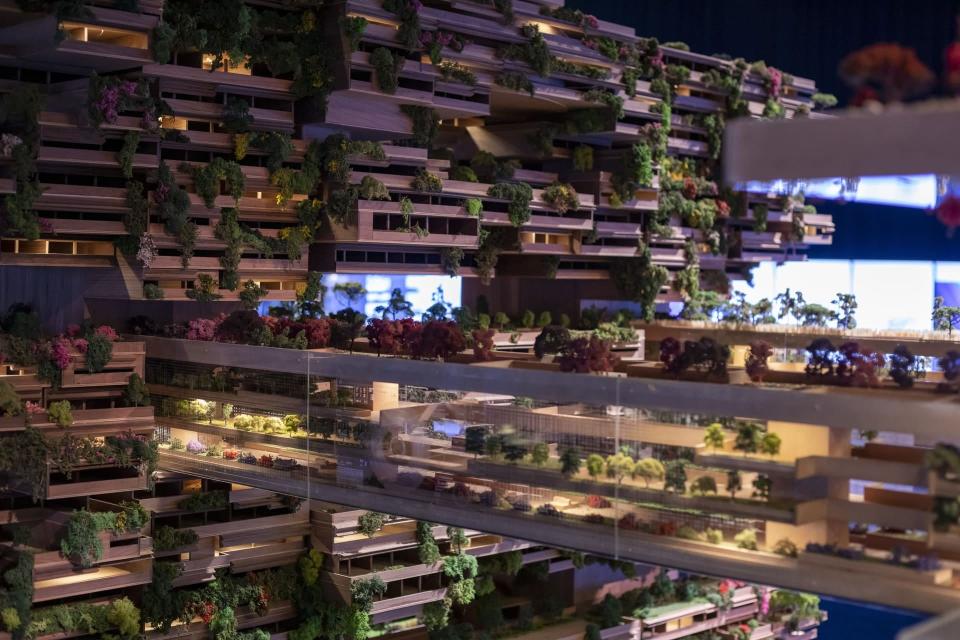

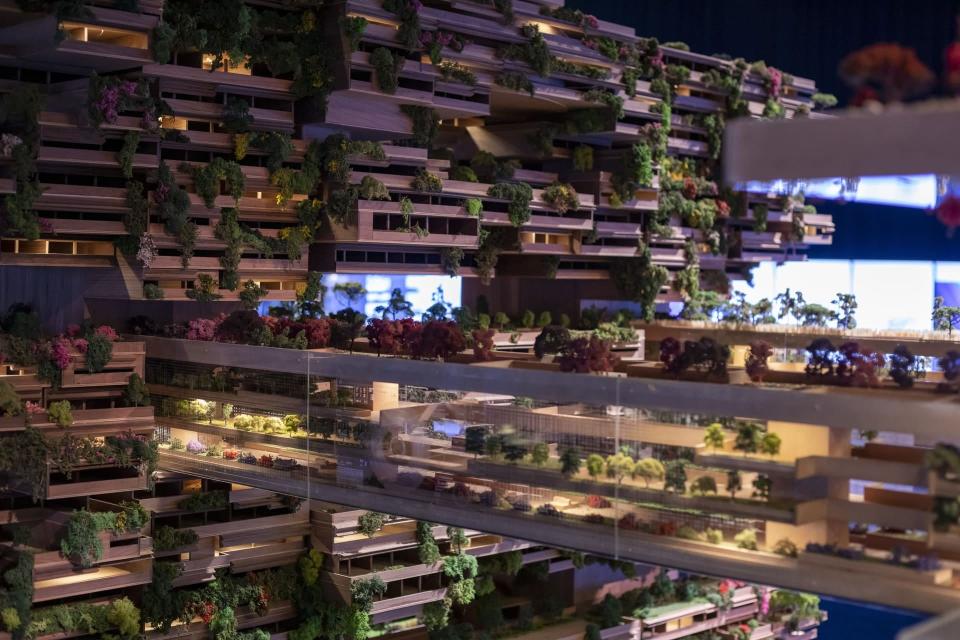

Saudi Arabia is building a giant city of mirrors in the desert.

The Line, as it was named, is a megacity with two skyscrapers that were originally meant to stretch out for 170km, with the aim of housing nine million people.

Officials called it an “architectural masterpiece” and a “revolution in urban life.”

Although recent reports suggest that the plans have been reduced in scale, the 2.4km still to be built will be the largest linear city in existence if completed.

As a concept, linear living is nothing new.

“It’s ambitious but hardly revolutionary,” Anirban Adhya, Professor of Architecture and Urban Design at Lawrence Technological University, told Business Insider.

After the Industrial Revolution, many urban planners looked to other city layouts to cope with growing populations.

Spanish architect Arturo Soria is widely credited with designing the first linear city, “La Ciudad Lineal,” in 1882 on the outskirts of Madrid. About forty years later, in 1924, the famous Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier offered a radical alternative with his “Ville Radieuse,” a linear, ordered city full of green space.

Soviet urbanist Mikhail Okhitovich was sent to a gulag in 1930 for his “economically” proposal to transform the city of Magnitogorsk into eight ribbon-like strips converging on a factory.

“It was common for urban planners to argue for a new future in response to what they say is ‘unsustainability;’ The current situation of the Line in Neom is no different,” said Adhya.

But revolutionary or not, is it a good idea to build a compact city in the shape of a line?

Compared to traditional layouts, the benefits of linear cities include efficient public transportation, easy access to nature, and a more balanced lifestyle. Theoretically unlimited, they can easily expand as populations increase.

Many of these commitments are in line with proposals for the Line.

The project’s website presents the city as a solution to mass urbanization and the climate crisis, portraying it as a sustainable wireless utopia that will conserve 95% of the region’s land.

Neom’s designers claim that all essential services will be accessible within five minutes, and nature will be only two minutes away. AI-powered technology across the city will improve sustainability and maximize the life expectancy of residents, they say.

“There is no one right shape for a city – they tend to change over time, based on natural, cultural, transportation, political and economic factors,” Mona Lovgreen, a partner at Canadian architecture firm DIALOG, told BI.

She believes that if designed correctly, the linear form of The Line would make it accessible and facilitate the integration of renewable energy sources along its entire length.

Although she said her goals may be exaggerated, Lovgreen believes The Line’s vision is admirable.

“It challenges us to rethink urban design and find new ways to make cities efficient, viable and sustainable.”

It could set a great example of how to use AI to improve sustainability and energy efficiency, something US urban planners should replicate, Lovgreen added.

The focus on convenience and services within reach also holds promise, Adhya said, pointing to successful examples already underway in cities such as Paris and Portland.

In “stocks and smaller pieces,” The Line’s linear structure could work, Adhya said.

‘Bland and monotonous’

Although there is potential in some practical aspects of the structure, all the experts BI spoke to saw fundamental issues with the living experience within linear cities.

“The Line could be a great place to visit and experience, but I’m still not sure if people are designed to live in such a rigid and prescriptive structure,” said Lovgreen.

The Line is made up of modules that 80,000 people can move around through a vertical and horizontal transport system.

“Compared to other urban designs such as a grid layout, radial layout, ring layout, or some combination of these, a strictly linear urban development may lack interest and variety in the human experience,” a Adhya explained.

“Certain parts of the city could become too long and segregated.”

The redoing of parts infrastructure and equipment would be “bland and homogenous,” lacking the unique character that other cities offer, Lovgreen said.

“Ultimately, living in such a regime environment could have a psychological impact on the well-being of the residents,” she told BI.

This type of structure is not only monotonous, but can limit social cohesion, according to John Gold, professor of Historical Urban Geography at Oxford Brookes University.

“Linear cities are a great form of urban sprawl – centrality is still needed in terms of community development and social cohesion,” Gold told BI.

Another challenge in Neom’s design is its over-reliance on technology and the public transport system, experts said. If something went wrong, the whole system would crumble, they warned.

“Most cities have network redundancy, where multiple options are available if a particular link or intersection is blocked. A linear city may not have this capability,” Lovgreen explained.

Finally, despite The Line’s announcement of sustainability, its massive mirrored walls could be ecologically harmful in terms of unnecessary heat build-up within the structure and detrimental to the migratory flight paths of billions of birds.

But the big question, according to Gold, is “who would want to live in a ‘city’ like that?”

“These schemes, and the Arab scheme, are a classic example of a high-tech utopian future, but they do not touch people as they really are. In my opinion, linear city schemes are best left as design exercises for students third-year architecture,” said Gold.

Read the original article on Business Insider