Earlier this year, researchers discovered that a huge liquid ocean lies beneath the icy shell of Saturn’s tiny moon, Mimas. Now the same team may have discovered how it was created.

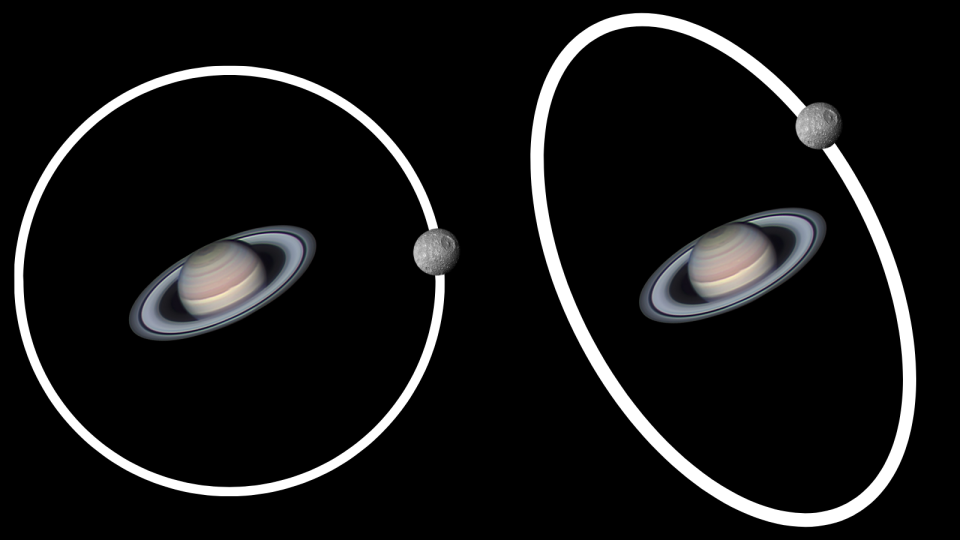

New research suggests that as Mimas’ orbit around Saturn became less flattened, or less “slippery” due to the encircling planet’s pull, its icy shell melted and thinned. This created a huge ocean somewhere between 2 million and 25 million years ago, which would make this subsurface sea relatively young for a solar system feature.

This small moon has already redefined what ocean life can be because moons this small were not expected to host subsurface oceans. This early discovery and new revelations about how this ocean came to be could have an impact on our search for life elsewhere in the solar system.

Related: Saturn’s ‘Death Star’ moon Mimas may have an ocean that scientists once believed could exist

“In our previous work, we discovered that for Mimas to be an ocean world today, it must have had a much thicker icy shell in the past. But because the eccentricity of Mimas would have been even higher in the past, the path should be found from. thick ice and thinner ice was less clear,” said team leader and Planetary Science Institute Senior Scientist Matthew E. Walker in a statement.

“In this work, we have shown that there is a path for the ice shell to be thinning right now, even as the outflow is falling due to tidal warming. However, the ocean must be very young, since from a geological point of view.”

A tiny moon with a big bay

Mimas is known as the “Death Star” because of Herschel’s crater, which gives the moon an appearance similar to the Empire’s lunar space station in Star Wars. This huge impact scar was created when Mimas collided around 4.1 billion years ago.

Mimas is only about 148 miles (400 kilometers) in diameter, making it relatively small compared to Earth’s moon’s diameter of 2,159 miles (3,475 kilometers).

The Mimas ocean is thought to lie about 12 to 18 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) below the surface of the icy crust of this Saturnian moon. The outer hydrosphere of Mimas, which consists of ice and water, is estimated to be 43 miles (70 kilometers) deep, and the moon’s ocean is estimated to be 25 miles to 28 miles deep (40 to 45 kilometers). This means that the oceans appear to be up to half of the volume of Mimas.

This new research has shed new light on a process that may have created these vast subsurface seas called tidal heating. This happens when a body like the moon is distorted or stretched by changes in its gravitational forces in an elliptical or oval orbit.

“Eccentricity drives the tidal heating. Right now, it’s very high compared to other active ocean moons, like neighboring Enceladus,” Walker said. “We think tidal heating is the heat source responsible for the current thinning of the shell.”

Walker added that the catch here is that tidal heating is not free energy, meaning that as it melts Mimas’ shell, tidal heating draws energy from the moon’s orbit around Saturn. Walker said this will further reduce the orbital eccentricity until eventually Mimas’ orbit becomes circular and the whole process is stopped for good.

Orbital eccentricity is measured in values from 0 to 1, with 0 being a perfect circle and 1 representing a parabola. Any value in between is an ellipse. The team estimates that ice melting must have started when Mimas’ orbital eccentricity was around two to three times its current value.

This represents the last 10 million years of Mimas’ history and presents an evolution consistent with the geology we see on the Saturnian moon today.

“In general, when we think about ocean life, we don’t see a lot of craters because we’re resurfacing and destroying them, like Europa or the south pole of Enceladus,” Walker said. “The shape, central peak, and uninterrupted interior of the Herschel crater require that the shell must have been thicker in the past when Herschel formed.”

He added that in order to obtain the crater morphology observed on Mimas, the Saturnian moon’s shell must have been at least 34 miles (55 kilometers) thick when it collided with the body that created the Herschel crater.

“Craters can provide clues to the presence of an ocean and the thickness of the ice shell through their morphology – such as the ratio of the diameter of the crater to its depth and the presence of a central peak,” Walker said.

RELATED STORIES:

– Spacecraft would detect life signals shot from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, scientists say

— Methane in the dust of Saturn’s moon Enceladus could be a sign of alien life, according to a study

— Saturn: Everything you need about the sixth planet from the sun

Walker added that in order to match the current eccentricity of Mimas’ orbit and the thickness constraints based on the slight wobble, or “library” in its rotation, they estimate that this entire ocean birth process must have started more than about 25 million . long ago.

“In other words, we think that Mimas was completely frozen until 10 to 25 million years ago, at which point its ice shell began to melt. What changed to start the era That meltdown is still under investigation,” Walker said. “We may see Mimas at a very interesting time.”

The team’s research appears in the journal Planetary Science Letters.