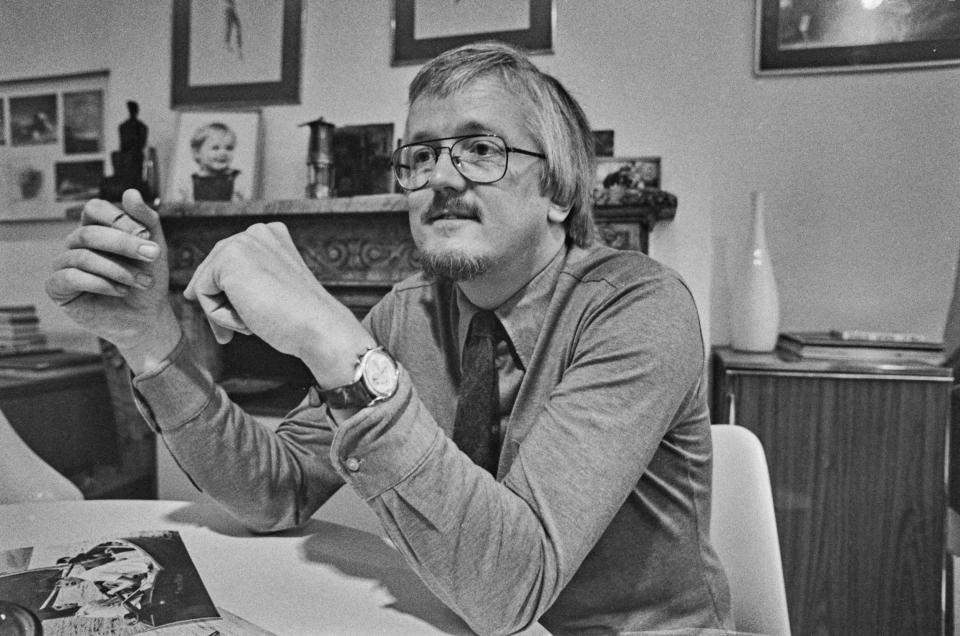

Richard Pilbrow, who has died aged 90, was one of Britain’s leading theater lighting designers, and one of the last survivors of the team assembled by Sir Laurence Olivier in the 1960s for the new National Theater on designing the South Bank. He was also the author of the lighting designer’s bible, Stage Lighting (1970), known as “the Old Testament”, and the 1997 revised edition, “the New Testament”.

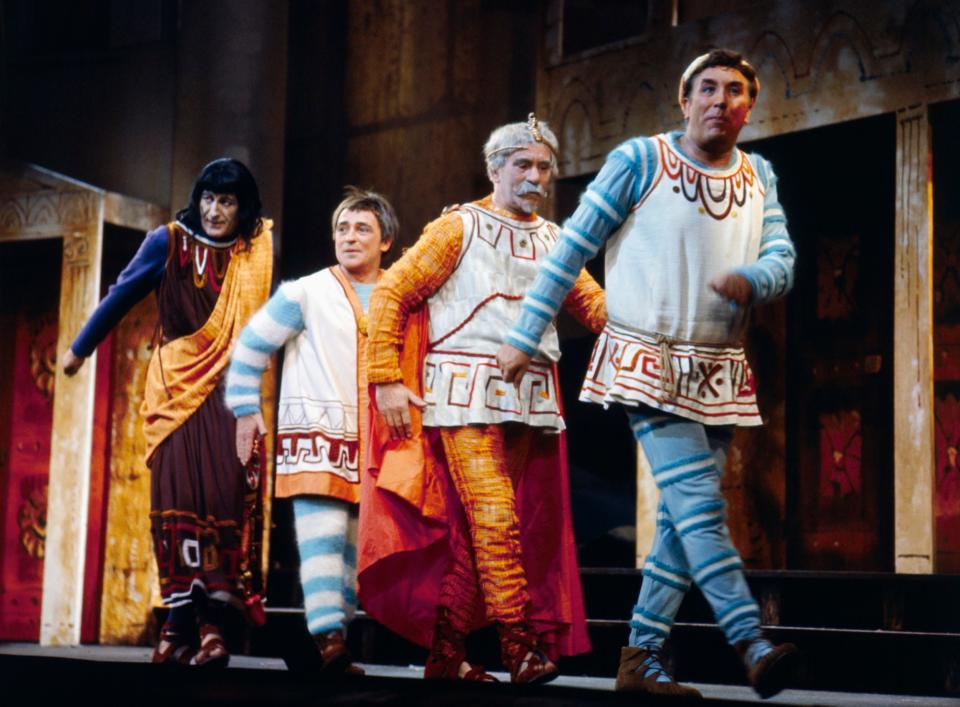

Pilbrow belonged to the first generation of lighting designers who were considered artists, rather than just electricians. By the early 1960s, he had established a reputation as a modernist, pioneering the use of film projection on stage in the Peter Cook/Kenneth Williams revue One Over the Eight (1961) and the Broadway production of A Funny Thing Happened on the. Way to the Forum (1962), which he then brought to the West End as co-producer.

In 1957, he founded Theater Projects, Britain’s first theater consultancy, which started by renting out lights salvaged from the stage at Drury Lane, and grew to become Europe’s largest supplier of theater lighting and sound, as well as shaping the design. of hundreds of theaters around the world. The Stage called him the “Bill Gates of the theater world”.

Olivier hired Pilbrow as lighting designer, first at Chichester Festival Theatre, and then, in 1963, for the National Theater Company, based at the Old Vic, where he lit Peter O’Toole’s Hamlet (1963), Love for Love (1966). ) and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966). He clashed with O’Toole, who wanted Pilbrow fired, but Olivier was impressed; he compared his own earlier expertise in light shows to “flying by the seat of our pants before and during the War”, compared to Pilbrow’s, which was “required to handle today’s jumbo jets”.

Meanwhile, the behavior of the National Theatre’s permanent home, on the South Bank, was painful. The architect Denys Lasdun was unanimously appointed in 1963 (partly because he was the only candidate who did not come with a self-improvement group) but the relationship then deteriorated into – as Lasdun put it – “pretty good hell”.

In 1966, Pilbrow joined the National Theater Building Committee, and found a pyrotechnic mix of egos. The “theatre men”, including Olivier, William Gaskill, Peter Brook and Peter Hall, clashed with each other and with Lasdun, who came close to resigning. No one could disagree about the wonderful new space (which was soon divided into two auditoriums, the open Olivier stage and the Lyttelton proscenium arch).

![Denys Lasdun unveiling his proposal from 1965 (subsequently abandoned) for a twin National Theater and Opera House, 'a series of platforms [cascading] into a central valley'](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/1y7.PUACB9pBayMCxHpyHA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk4MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_telegraph_818/ae25cf1d36d040c4c6e372e7a5224131)

![Denys Lasdun unveiling his proposal from 1965 (subsequently abandoned) for a twin National Theater and Opera House, 'a series of platforms [cascading] into a central valley'](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/1y7.PUACB9pBayMCxHpyHA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk4MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_telegraph_818/ae25cf1d36d040c4c6e372e7a5224131)

“I was the only person backstage,” Pilbrow told Daniel Rosenthal, author of The National Theater Story. “Lasdun gradually got into the habit of seeking my opinion as to which of…two other possibilities might be a bit more practical.” Pilbrow went to various West End theaters with Sir Laurence Olivier, to measure how long, in Olivier’s opinion, the audience could sit. From these tests they set the limits for the two large theaters of the National Theatre: 65ft.

In 1967, Theater Projects were appointed as the National’s official stage and lighting consultants. Pilbrow’s most daunting task was to succeed on the opening stage of the Olivier Theatre.

By 1973, construction was underway, and he was on holiday on the island of Coll with sound engineer David Collison. On the beach, they drew an excellent plan for the Olivier Theatre, which was a top secret at the time. (“I hope no helicopter flies over us with a camera,” Pilbrow said.) When they watched it from the nearby hill, they were in awe: “It was huge” – 2.5 times width of the Old Vic.

Pilbrow came up with an innovative revolving drum, which consisted of two semi-circular elevators. It was the world’s first open stage that could accommodate almost any scenery imaginable, thanks to a fully computerized flight system of 127 trees (albeit plagued with bugs). Lasdun was furious at first: “I am the architect, how dare you! Your ‘ears’ on my flying tower will change the silhouette of my buildings and the London skyline forever!”

Pilbrow designed the more traditional Lyttelton (which he bleakly described as a giant Odeon cinema) so that entire sets could be placed on trolleys, which he likened to “big tea trays”.

After many years of delay, Peter Hall, who succeeded Olivier as director of the NT in 1973, ordered that plays must begin to be performed in the theaters that had not yet been completed. Pilbrow had to make sure there was a floor for the actors to stand on, and electricity so they could turn on the lights. “Sophisticated computers were coming in for the flight and the lighting and the sound, in rooms that weren’t plastered,” he said.

The Olivier and the Lyttelton opened in 1976, but Pilbrow was not happy with either. “Great theater people have overcome these challenging spaces, but my heart still longs for more actor-friendly spaces in our National Theatre,” he said.

He had his chance in 1973 when he was asked to advise on the Cottesloe (now renamed the Dorfman), a huge hole under the backstage of the Olivier. The sketch design was done by Iain Mackintosh, a new recruit for Theater Projects, whose vision was for a courtyard, spartan in decoration but “packed with people on three levels”, so that the audience would “see the furniture finish as wallpaper does room. ”, as Mackintosh recalled.

The Cottesloe opened in 1977 and inspired many imitators. It was a damascene moment for Pilbrow, who led the pushback against the 1930s to 1970s fashion for huge, fan-shaped auditoriums and instead revived the old fashioned stacked balconies of 18th century opera houses. , bringing as many of the audience as possible as close to the actors.

“Tradition has accepted relationship as the main desirable characteristic of the theater, and the best is the miracles of compressed humanity,” he said. The mid-century “rules” of perfect sight lines, no old-fashioned boxes and no balconies, were “wrong”. “We had a rich tradition of theater design that emphasized the essential since the days of Shakespeare: contact between performer and audience.”

Richard Pilbrow was born in Beckenham on 28 April 1933 to Gordon, an Olympic fencer, and his wife Marjorie, a music teacher. He attended Bickley Hall preparatory school, where he spent hours gathering details on West End shows and performing with Pollock’s Toy Theatre, and then Cranbrook School. After serving as a corporal in the RAF, he studied stage management at the Central School of Speech and Drama.

When he graduated in 1955, he began his theater career as assistant stage manager at Queen’s House; two years later, he borrowed £60 from his father to set up Theater Projects Ltd with his assistant Bryan Kendall. He then made his name at the Hammersmith Lyric with a string of hits in the late 1950s.

Harold Prince, the Broadway producer with whom he brought A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum to London in 1963, asked him to execute the film projection feature of Golden Boy (1964), the Broadway musical by Sammy Davis Jnr. In 1968, Pilbrow was the first English lighting designer to be commissioned with the entire lighting scheme for the original Broadway musical, Zorba. He was one of the first English designers to be invited to join the United Scenic Artists, and won Tony nominations, a Drama Desk award, and an Outer Critics award for his lighting.

Meanwhile, in the West End, he produced – in partnership with Prince – Fiddler on the Roof with Topol, Cabaret with Judi Dench, and Stephen Sondheim’s Company and A Little Night Music, and also worked on Edward II and Richard II by Ian McKellen, I. ‘m Not Rappaport by Paul Scofield, She Stoops to Conquer by Tom Courtenay, The Ruling Class by Peter Barnes, and the fiasco that was TWANG!

In the 1970s, Pilbrow moved into films, notably producing Swallows and Amazons (1974), which was filmed in the Lake District; there was a small scandal when it came to light that a member of staff was seducing local girls while claiming to be Richard Pilbrow.

In the early 1980s, Theater Projects almost went under, but Pilbrow survived by selling the lighting services and retaining the consultancy, which proved successful. As a theater consultant, Pilbrow shaped the Barbican, the Royal Exchange Theater in Manchester, and Glyndebourne, among many others; Theater Projects has completed over 1,800 projects in 80 countries, including many major venues in the US, where Pilbrow has lived since 1988.

He was a co-founder of the Society of Lighting Designers, the Society of British Theater Technicians, the Institute of British Theater Consultants, and the Society of British Theater Designers. In 2011, he published a memoir, A Theater Project. His final book, A Sense of Theatre: The Untold Stories of the Creation of Britain’s National Theatre, will be published next year.

Richard Pilbrow married, firstly, in 1958, Viki Brinton, a partner in the early days of Theater Projects, with whom he had a son and a daughter; and secondly, in 1974, lighting designer Molly Friedel, who had another daughter.

Richard Pilbrow, born 28 April 1933, died 6 December 2023