How much does Whitehall hate rural voters? We should be alerted if ravenous predators are released into the countryside. Now beleaguered rural voters face complete isolation from modern life.

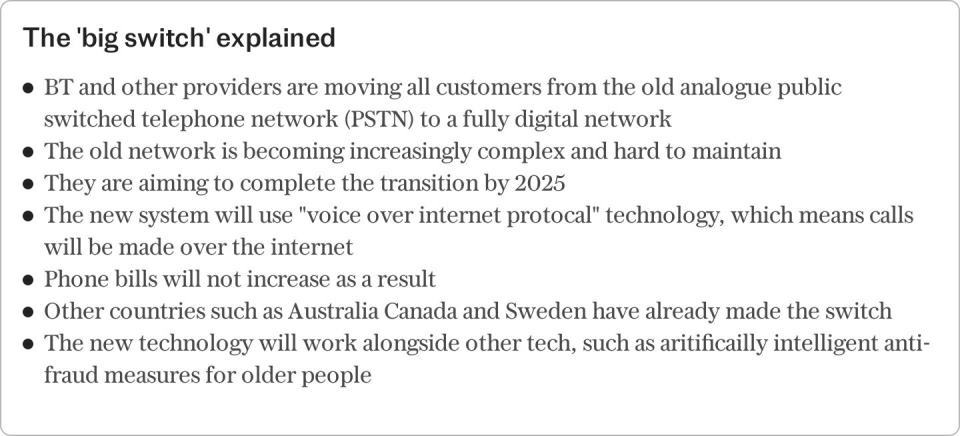

The old BT circuit-switched phone network is being switched off and replaced with a digital service – meaning when the power goes out, so does the phone.

More than 1 million customers lost power in Storm Arwen in 2021, and about 4,000 went dark for more than a week. That’s a long time without a 999 service. So gradually the reliable mobile service in the countryside.

Except, our mobile network operators chose to shut down 3G services, and this surprised quite a few. Some parts of the country haven’t seen 4G at all and the 3G shutdown affects some telecare devices, connected cars and smart meters.

Can the Shared Rural Network (SRN) project be successful now? This is the ambitious £1bn scheme announced four years ago which promised to increase competition and eliminate dead zones, or spots left, entirely by 2027.

That was the plan, anyway. But only one of the four operators, EE, will reach the first milestone, largely thanks to its ability to use its own legacy infrastructure – EE runs the nation’s Emergency Services Network.

The other three operators had to build new sites, and were refused extensions. Ofcom can now impose fines on them – which will not help anyone to bind.

Although the SRN website boasts that 1500 tree sites have been upgraded, you could be forgiven for not noticing any difference. Operators blame NIMBYs, local authority planning departments, EE for not sharing their sites, and even the Covid. How British: everyone is to blame but no one wants to own it.

In mitigation, there is no objection that building new rural infrastructure is expensive, and the operators must foot the full bill for phase one. The cost of a new site can be more than a million pounds, and at least one, I’m told, requires a diesel refueling helicopter to fly in.

But one complicating factor is pure goal itself. Have you ever stood in the street, or in your garden, cursing your network for not giving you a decent signal, only to check the operator’s maps and Ofcom coverage and be told everything is fine ?

These mobile cover maps have been a joke for years, and have as much correspondence to reality as Hogwarts resembles a typical middle school.

That’s not surprising when you learn how they are put together. Ofcom outsources the job to the operators, who then drive around but not with real phones.

“They’re measuring signals, not testing performance,” explains an insider familiar with the process.

This data goes into a large computer model and is then handed over to Ofcom – which validates it but does not carry out its own thorough tests. So maybe Hollywood CGI is what we see as well.

This means that no one can tell if those million pound sites were placed in the right place, or if the networks fulfilled their promises at all.

All this malarkey is too much for rural champion and Liberal Democrat MP for North Shropshire Helen Morgan, who tabled a private member’s bill to force the industry to raise its game on rural mobile coverage and performance. Morgan also led a debate on the issues, including the comical cover maps, last month.

“The industry is going to get away with the Shared Rural Network not being as high a standard as it should be, than we expected when it was announced,” she says.

There is definitely some focus on it. Some better equipment needs new ideas from the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) – a newer technology called “neutral host” works well on new metro networks like the London Tube – and better coverage maps are needed from her too.

Fundamentally, however, governments have failed to acknowledge that non-profit sites need cash and make the case for them. Instead for many years, there has been a series of compromises that no one likes.

David Cameron spoke of mandating roaming between networks – and for very good technical reasons too, as it could lead to a cascade of failures.

Operators are not keen on sharing, or universal performance obligations, because who knows where this could lead?

“There’s an ideological battle here that’s not really capitalism versus communism, it’s the competition purists versus physics versus geography,” says Dean Bubley, an analyst at Disruptive Analysis.

In some countries, like France, he explains, the rules for fixed broadband in rural areas are relaxed. But mobile operators hate that too.

Morgan tells me that her bill aims to put a Sword of Damocles over industry: “We’re going to mandate rural roaming to get the service we need.”

Perhaps a future Labor Government will be less aggressive about making the case for new infrastructure. But note that it was Back Bench MPs like Morgan who raised the issue. Labor is asleep on the issue, and after the general election, there will be fewer voters to care about outside the cities and University towns.

A rural communications arrangement not only benefits the people who live there, SW1 should remember, but the whole country. It enables mass relocation as urbanites are increasingly eager to escape the rougher texture of life in our cities, buying homes and starting families on greener pastures.

But they have to be confident that the modern webs exist before they do. Revival of the forgotten countryside should be a national priority – and networks should do their part.