Racism steals time from people’s lives – perhaps because of the space it occupies in the mind. In a new study published in the journal JAMA Network Open, our team showed that the toll of racism on the brain was associated with progressive aging, observed at the cellular level.

Black women who were exposed to racism more often showed stronger connections in brain networks associated with rumination and vigilance. We found that this, in turn, was linked to accelerated biological aging.

We are neuroscientists who use a variety of approaches, including self-report data and biological measurements like brain scans, to answer our questions about the effects of stressors on the brain and body. We also use this data to inform the development of interventions to help people cope with this stress.

Why is it important

Aging is a natural process. However, stress can speed up the biological clock, making people more vulnerable to age-related diseases, from cardiovascular disease to diabetes and dementia.

Epidemiological studies consistently show that blacks develop these aging-related health problems at an earlier age than whites. New studies also show focal effects of aging on the brain, indicating differences in brain aging between Black and white populations.

Race-related stressors, including racial discrimination, affect the rate at which people age at a biological level. These experiences activate the stress response system and are linked to increased activity in brain regions that process incoming threats. However, until now, researchers in our field did not understand how racism-related brain changes contribute to accelerated aging.

Racial discrimination is a ubiquitous stressor that often goes unnoticed. It could be like a doctor questioning a Black patient’s pain level and not prescribing pain medication, or a teacher calling a Black child a “thug.” It is a constant stressor that Black people experience starting at a young age.

Rumination – reliving and analyzing an event – and vigilance, which means watching out for future threats, can be responses to deal with these stressors. But rumination and vigilance take energy, and this increased expenditure of energy has a biological cost.

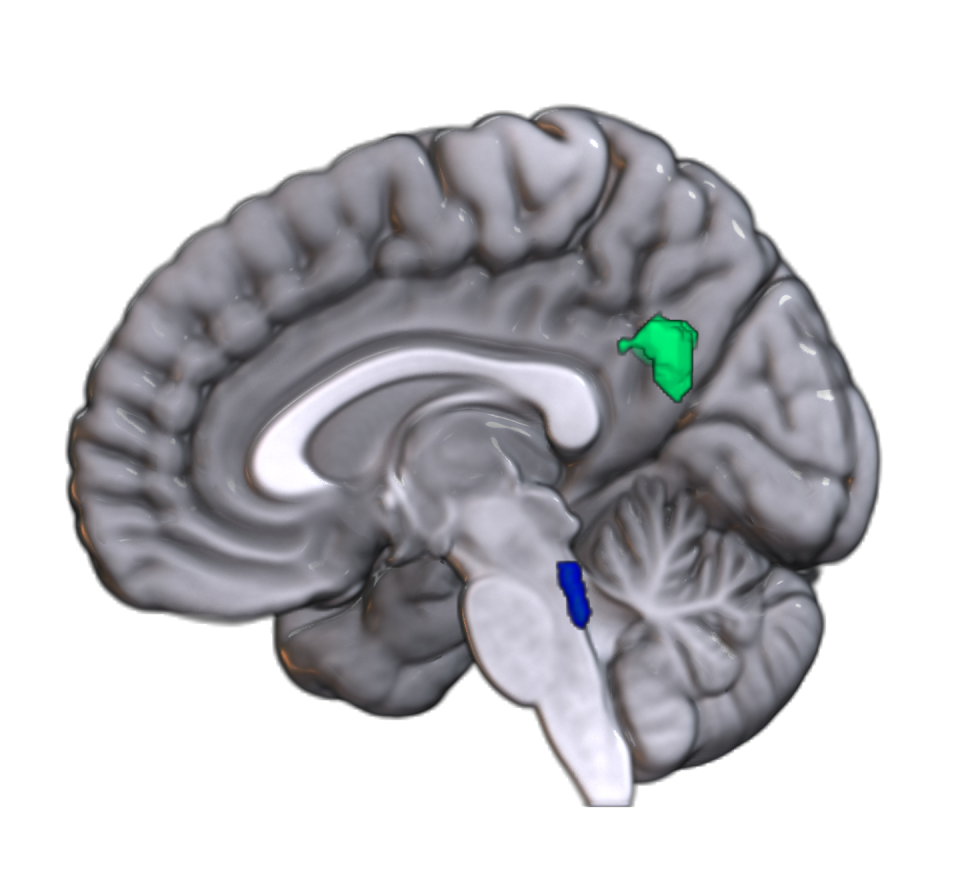

In our study of Black women, we found that more frequent racial discrimination was linked to greater connectivity between two key regions. One is a deep brain region, called the locus coeruleus, that activates the stress response, promoting arousal and vigilance. The other is the precuneus, a central node of a brain network that engages when we think about our experiences and internalize – or repress – our emotions.

These brain changes, in turn, were linked to accelerated cellular aging as measured by an epigenetic “clock”. Epigenetics refers to changes that occur to our DNA from the environment. Epigenetic clocks assess how the environment affects our aging at a molecular level.

Higher clock values indicate that a person’s biological age is higher than their chronological age. In other words, the space that racial experiences occupy in people’s minds has a cost, which can shorten the lifespan.

What is not known yet

While we saw links between racism, changes in brain connectivity and accelerated aging, we didn’t measure coping responses like rumination and vigilance in real time, meaning people were actually experiencing them.

We also do not know how other factors such as neighborhood disadvantage, gender and sexuality intersect to influence accelerated aging and related health disparities.

What lies ahead

Our next steps are to use real-time measurement of everyday racism as well as physiological measurements and neuroimaging to gain deeper insight into these research questions.

We want to know how different types of racial discrimination and coping styles affect brain and body responses. A better understanding of these issues can lead to greater attention to prevention, such as programs that target implicit bias in physicians and teachers. It can also provide information on interventions such as neuromodulation, which involves the use of external or internal devices to stimulate or inhibit brain activity. Neuromodulation can be used as a therapy aid to reduce stress.

The Research Brief is a brief overview of interesting academic work.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by: Negar Fani, Emory University and Nathaniel Harnett, Harvard University.

Read more:

Negar Fani receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and Emory University School of Medicine.

Nathaniel Harnett is an Assistant Professor at McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School. He receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, McLean Hospital, and Harvard Catalyst.