Because of the same stability and resistance to degradation that makes these chemicals valuable for waterproof and stain-resistant products, they are almost impossible to destroy. Hence the nickname “chemicals forever.” They remain in the environment for years to hundreds of years.

That’s a problem, because PFAS have been linked to immunological disorders, endocrine, developmental, reproductive and neurological disruptions and an increased risk of bladder, liver, kidney and prostate cancer. A study of drinking water by the US Geological Survey estimated that at least 45% of tap water across the US contained these chemicals, and it is now believed that a large percentage of Americans have detectable PFAS in their blood. The EPA finalized the first federal drinking water standards for PFAS on April 10, 2024.

Studies have also found PFAS in a wide range of marine wildlife, including in otter liver and seagull eggs, and in freshwater fish across the U.S. These chemicals have already been shown to affect the immune system and on fish liver function. and marine mammals.

How PFAS enter the marine environment

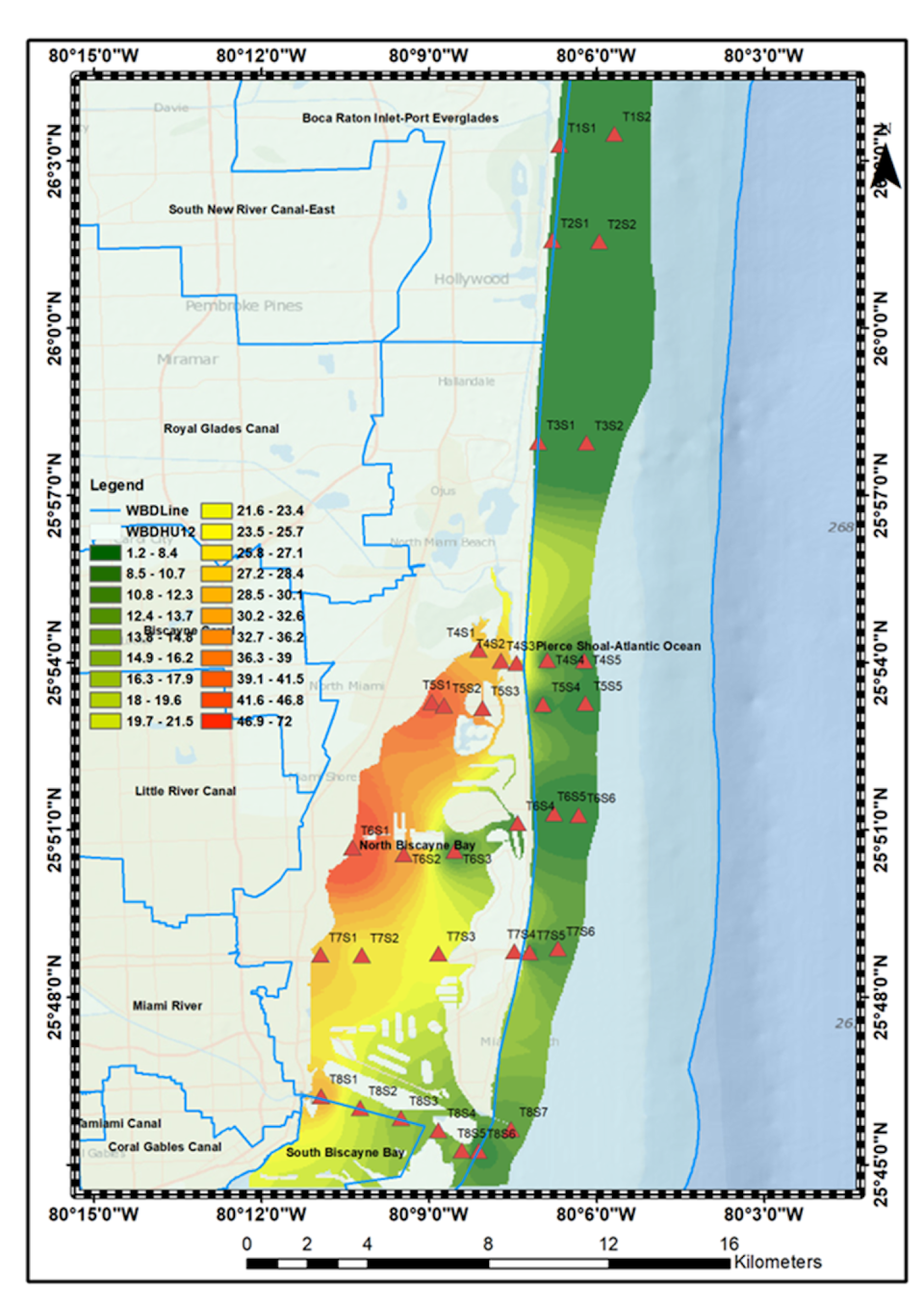

When we started tracking the sources of PFAS in Biscayne Bay, we found hot spots of these chemicals around the exits of urban canals – especially the Miami River, the Little River and the Biscayne Canal. We found that each of these canals is a major source contributing to the presence of PFAS in offshore areas of the Atlantic Ocean.

One major source of such PFAS is sewage contamination from failed sewage systems and wastewater leaks in urban areas. This is evident in the presence of types of PFAS – such as PFOS, PFOA, PFPeA, PFHxS, PFHxA, PFBA and PFBS – used as stain and grease repellants and in carpets, food packaging materials and household products.

Another major source is indicated by the excess of 6-2 FTS in the Miami River – 6-2 FTS is a fluorotelomer PFAS commonly used in aqueous film forming foams found at military facilities and airports. The Miami River flows past railroad yards, industries and Miami International Airport on its way to Biscayne Bay.

We also used a model to predict how ocean currents would disperse PFAS coming out of those canals and into coastal areas. We found that PFAS concentrations were highest near the canals, decreased along the bay and decreased as seawater became deeper and saltier, making PFAS less soluble in water.

Overall, PFAS concentrations were nearly six times higher in surface waters near land compared to deep-water samples collected 13 to 33 feet (4 to 10 meters) below the surface of the bay and offshore. This suggests that the risk is highest for pelagic fish that hang out in surface waters, such as mackerel, tuna and mahi-mahi.

How are marine organisms endangered

The levels of PFOS and PFOA in our study were below the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s advisory levels in surface water for human health exposure. However, the advisory levels may not be protective of human and marine life.

They do not take into account that these chemicals accumulate through the food chain. Higher concentrations at the top of the food web mean PFAS may pose a greater risk to dolphins, sharks and people who eat fish.

Many types of PFAS identified in our samples are not regulated, and their potential toxicity is unknown. We believe that federal and state agencies are needed to develop guidelines and implement action plans to protect people and aquatic life in the Bay of Biscayne.

What can you do about it

Due to the persistence of PFAS and their widespread use, it is not surprising that these chemicals are found forever in almost every water system in South Florida and are showing up in coastal waters around the world.

While scientists look for effective and efficient ways to eliminate and remove these chemicals from water, food and the environment, people can limit their use of products containing PFAS to reduce the amount of these chemicals entering the marine environment to reduce.

Some common products that contain PFAS to look out for include: non-stick Teflon cookware; food packaging for fast food and popcorn; waterproof clothing and cosmetics; and treated carpets.

This article was updated on April 10, 2024, and the EPA issued the first federal drinking water standards for PFAS.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Natalia Soares Quinete, Florida International University and Olutobi Daniel Ogunbiyi, Florida International University

Read more:

Natalia Soares Quinete receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

Olutobi Daniel Ogunbiyi receives funding from the National Science Foundation awarded through FIU’s Environmental Institute and Center for Research and Excellence in Science and Technology.