American model Peggy Moffitt, who has died aged 84, teamed up with designer Rudi Gernreich to scandalize the 1960s fashion world in baby doll dresses, adult school uniforms and – most notably – women’s topless swimwear criticized on the beach. – area police forces from Santa Monica to St Tropez.

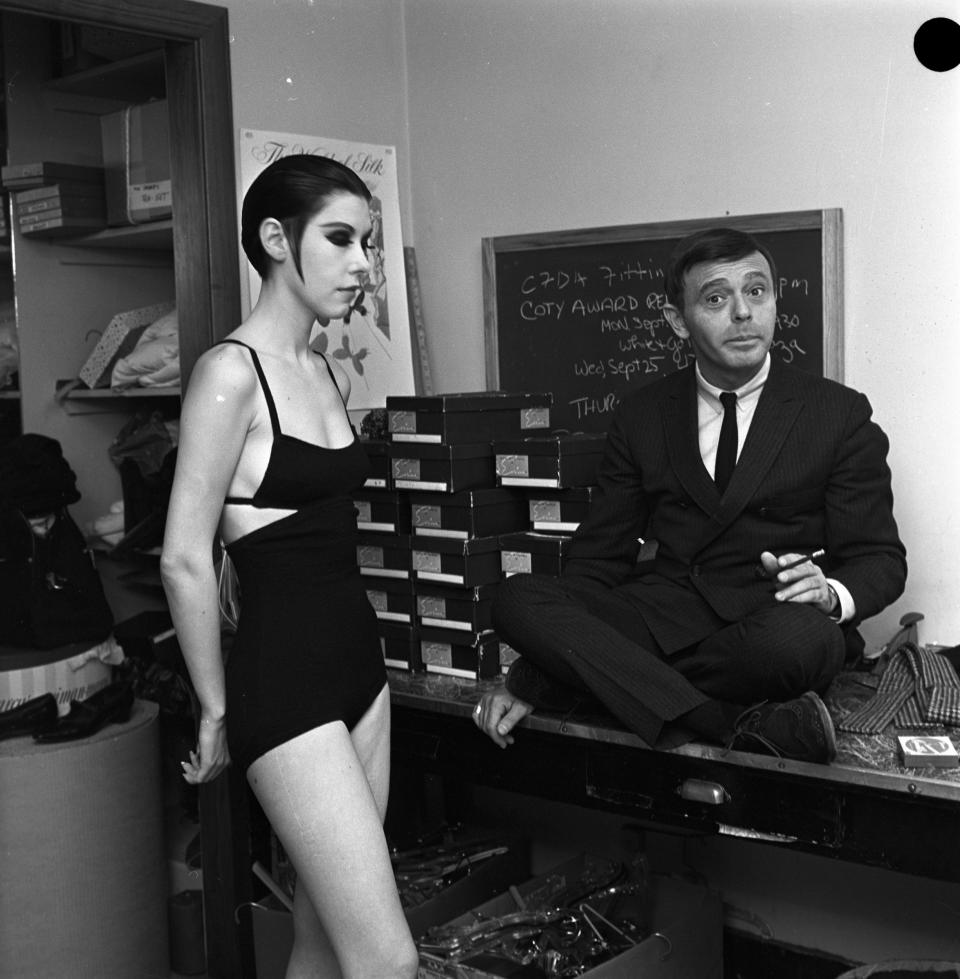

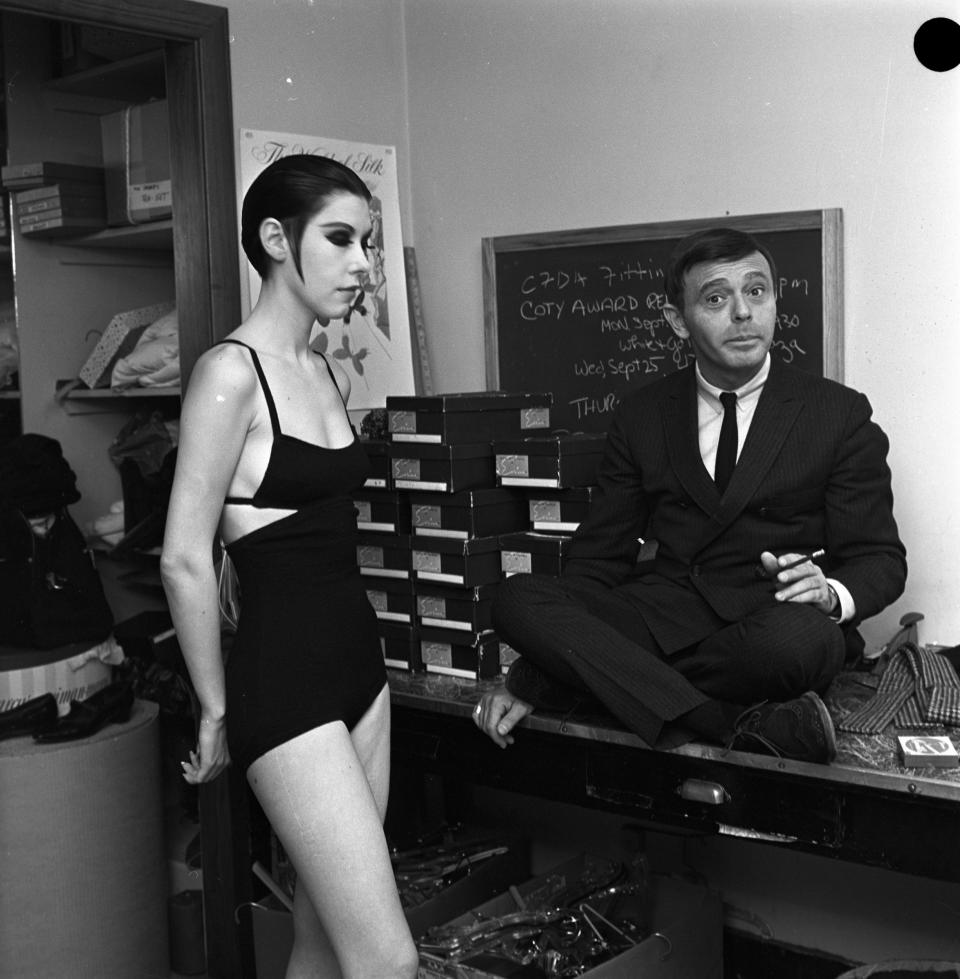

The image of Peggy Moffitt in Gernreich’s “monokini”, taken by her photographer husband William (Bill) Claxton, became a symbol of the era’s sexual revolution and liberation. It was featured in Women’s Wear Daily in 1964 and made international headlines. France issued a ban on swimsuits; the Pope declared it immoral and the Soviet government denounced it as a sign of “barbarism” and social “leprosy”. Peggy Moffitt received both marriage proposals and threats.

Gernreich designed the monikers as a statement against American purity and the taboos associated with female nudity. Only around 3,000 topless swimsuits were ever produced; One, a gift from Gernreich himself, remained in Peggy Moffitt’s wardrobe, with the garment worker’s tag still on it. She kept it as a tribute to their friendship, which lasted until Gernreich’s death from lung cancer in 1985.

Afterwards she became the guardian of his heritage, and a staunch defender against any perceived attempt to destroy it by excessive indulgence. She vociferously objected to the Los Angeles Fashion Group’s plans to use a topless model as part of Gernreich’s retrospective, declaring the move “exploited”.

During their 20 year partnership she did not see herself as the mind of the designer, but as her collaborator, with equal say in how an image was put together and presented. She brought her experience of ballet, theater and mime to each shot, treating the photograph as a “seamless piece of blank paper” to illustrate.

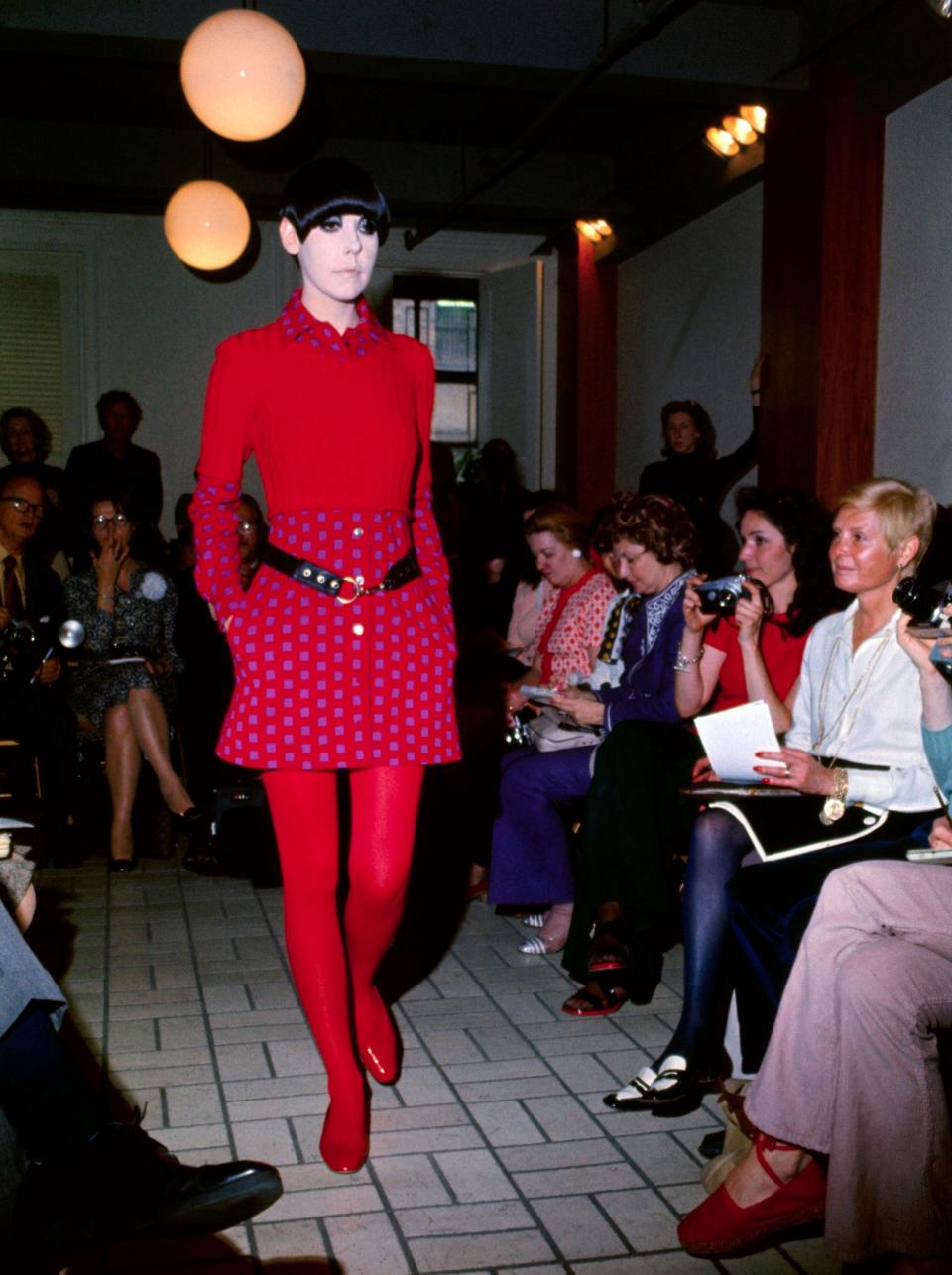

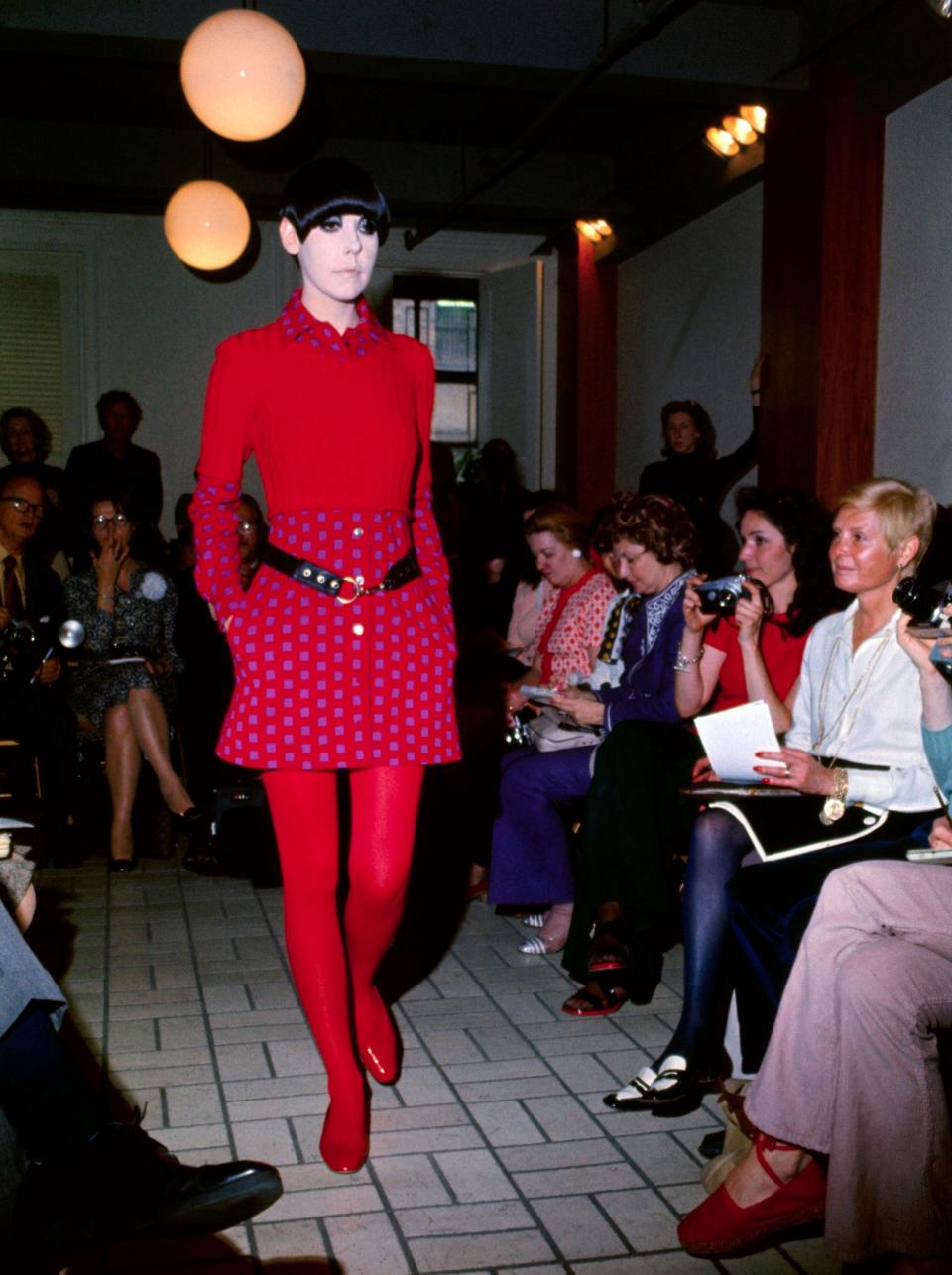

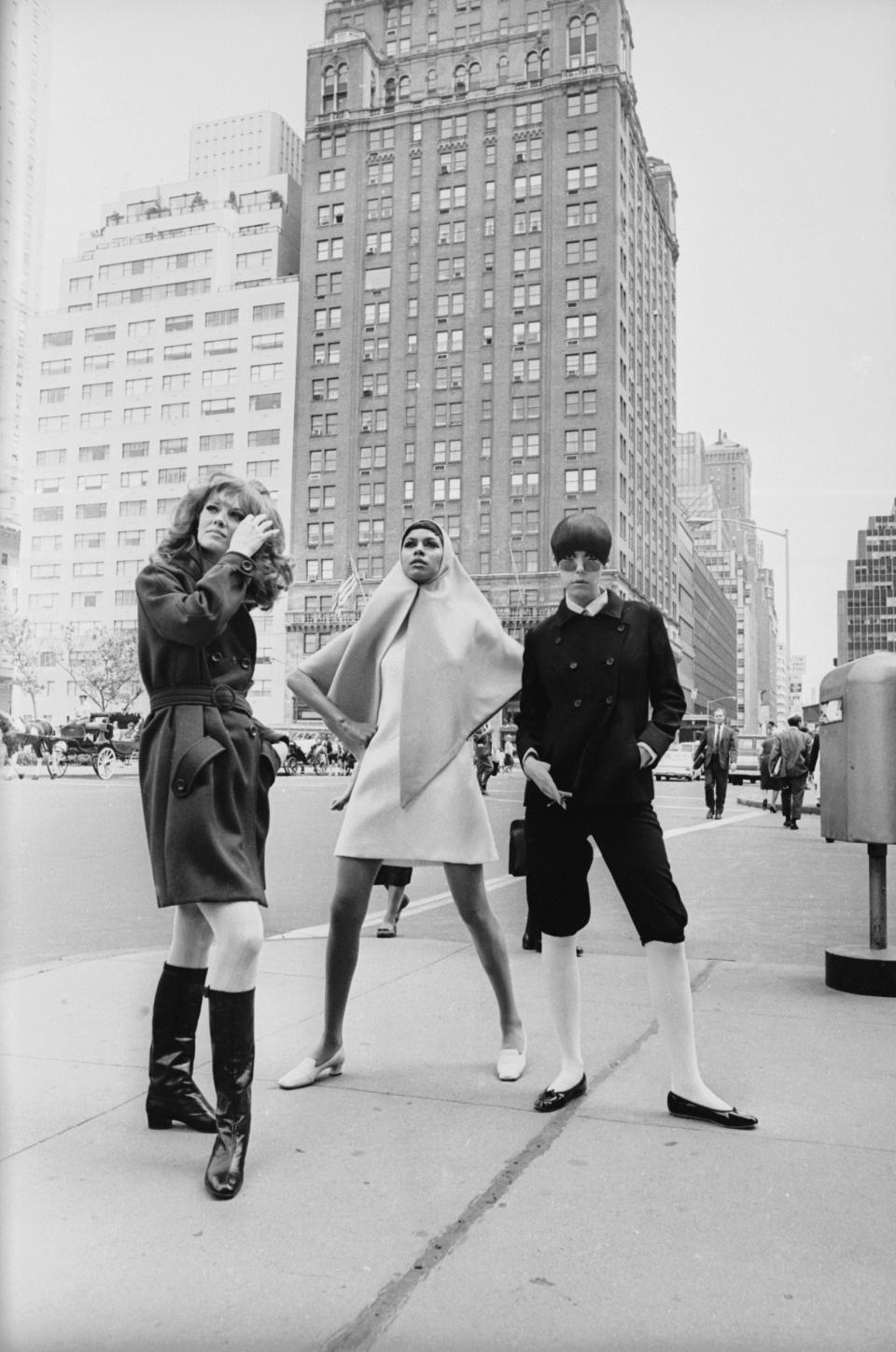

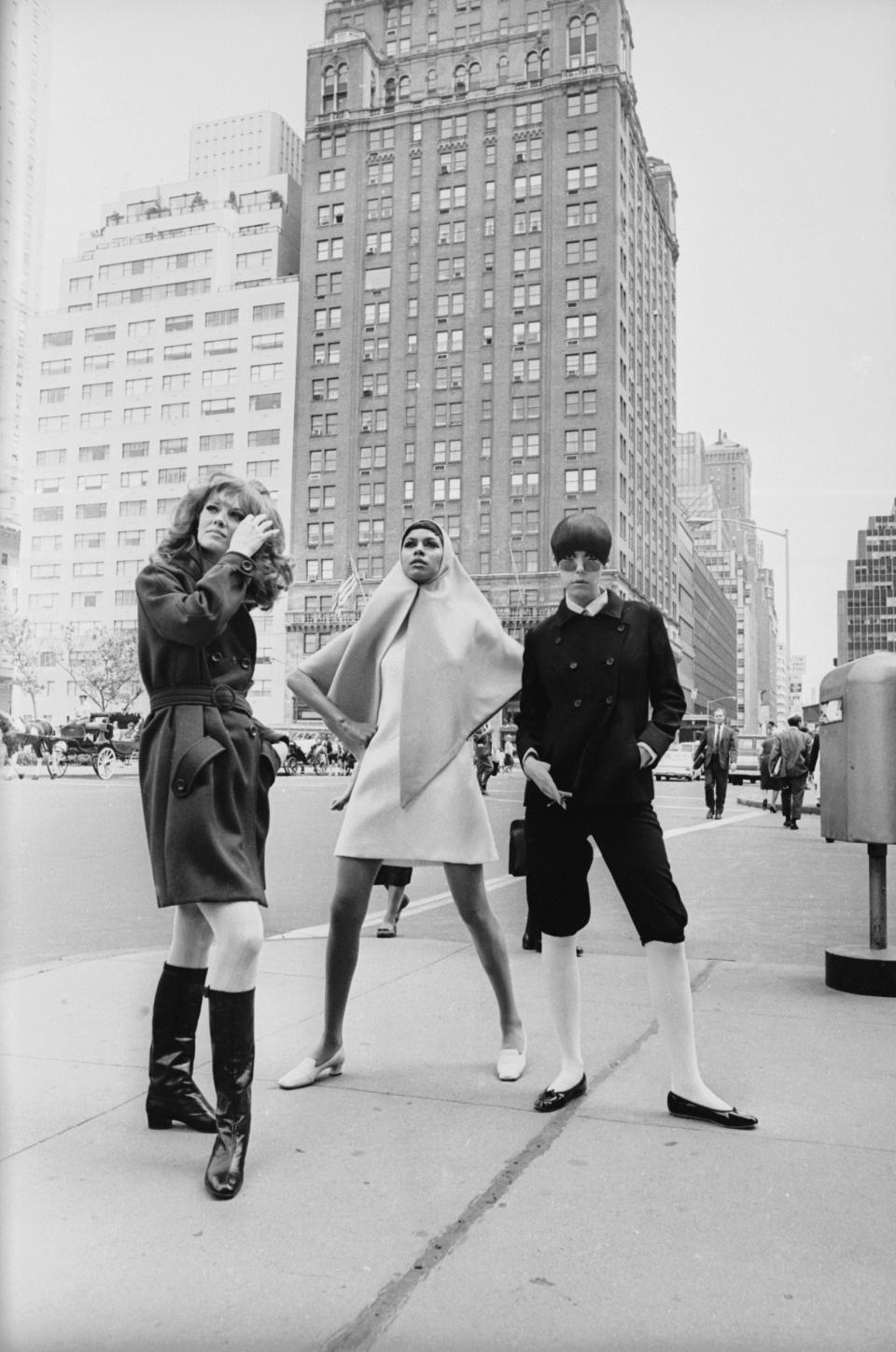

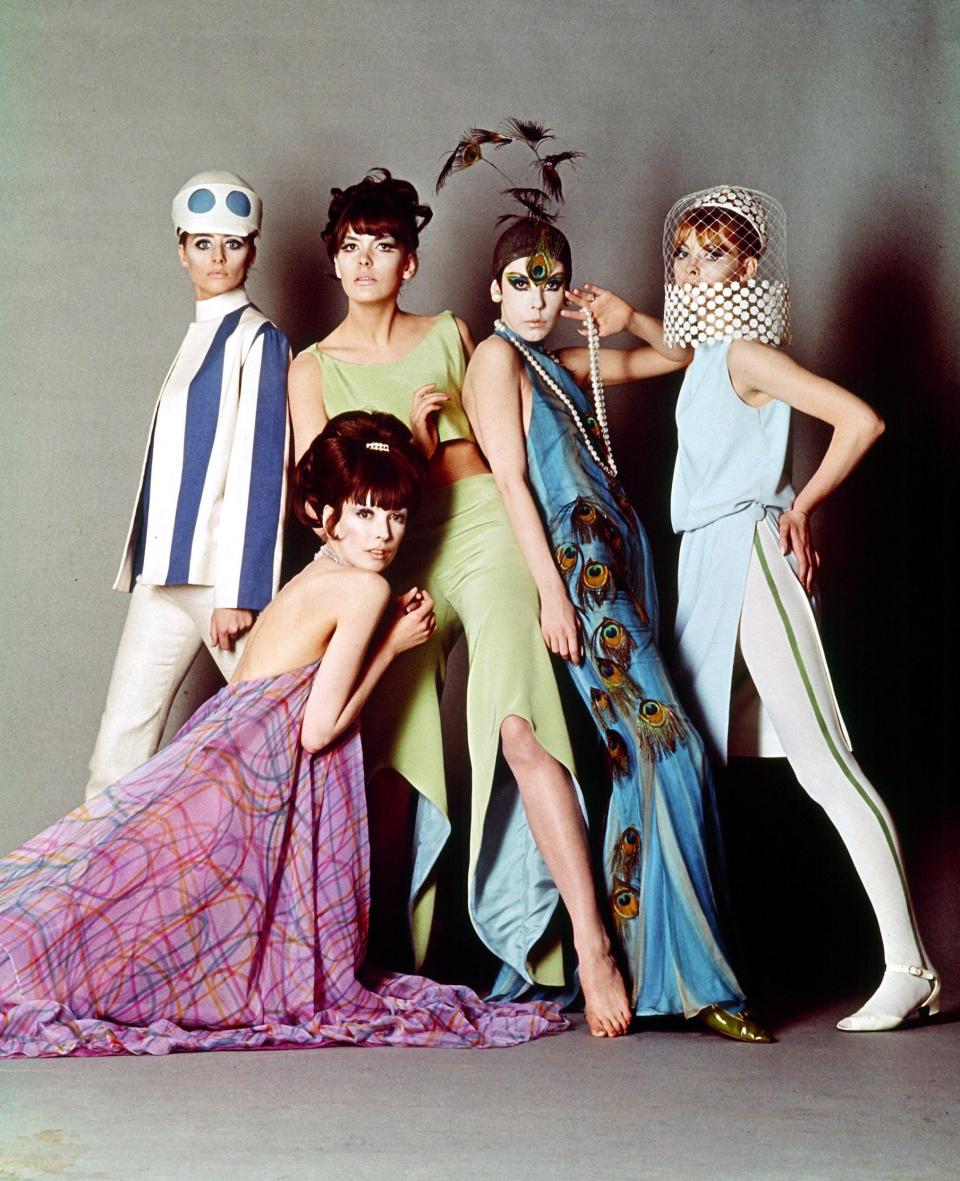

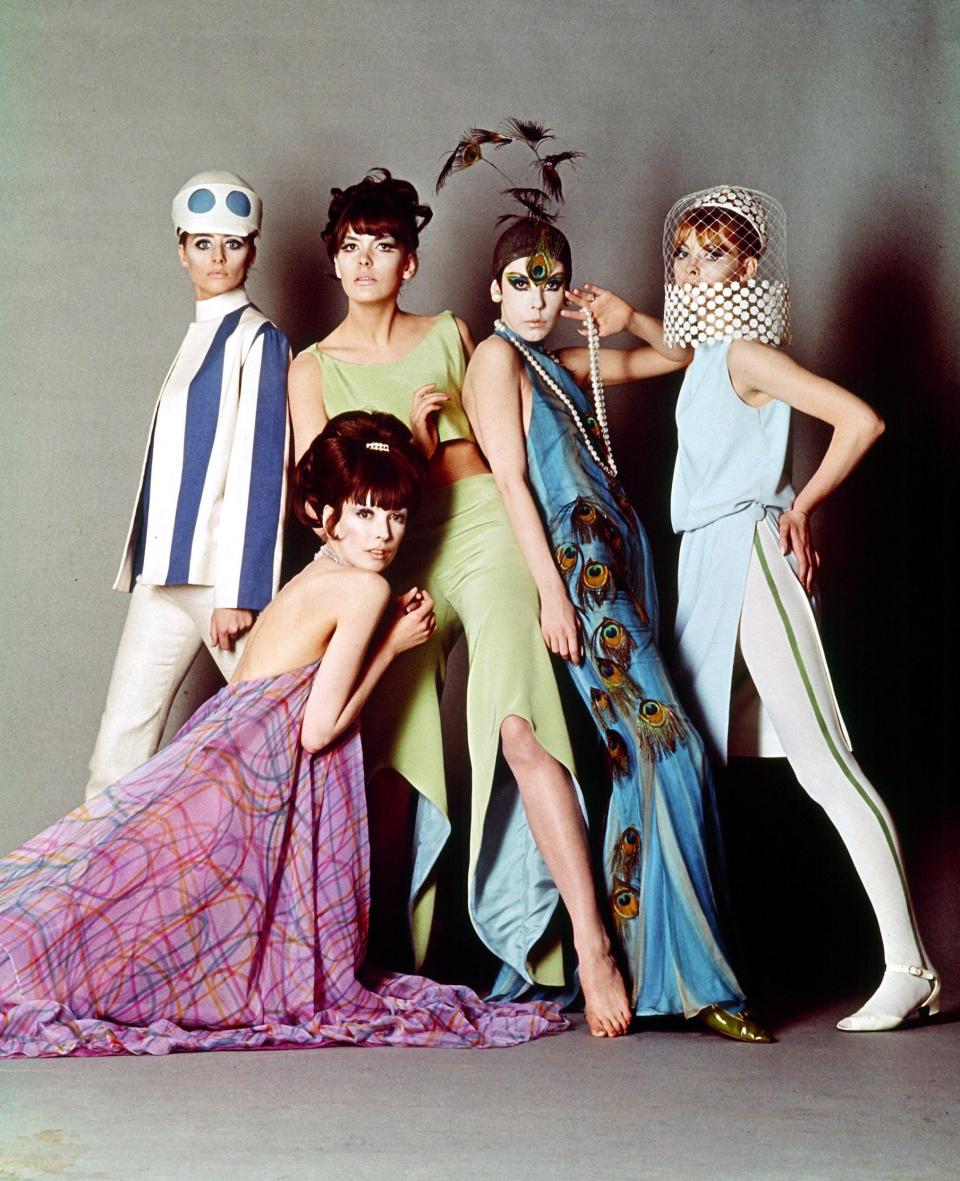

Runway shows were theatrical events, with original dresses as stage costumes. While other models were strutted in the approved way, she would walk knee-high and dove if she felt the outfit was necessary. “I want to look for the life inside the dress, and when I made a whole collection, I want to figure out how to play each of them,” she said.

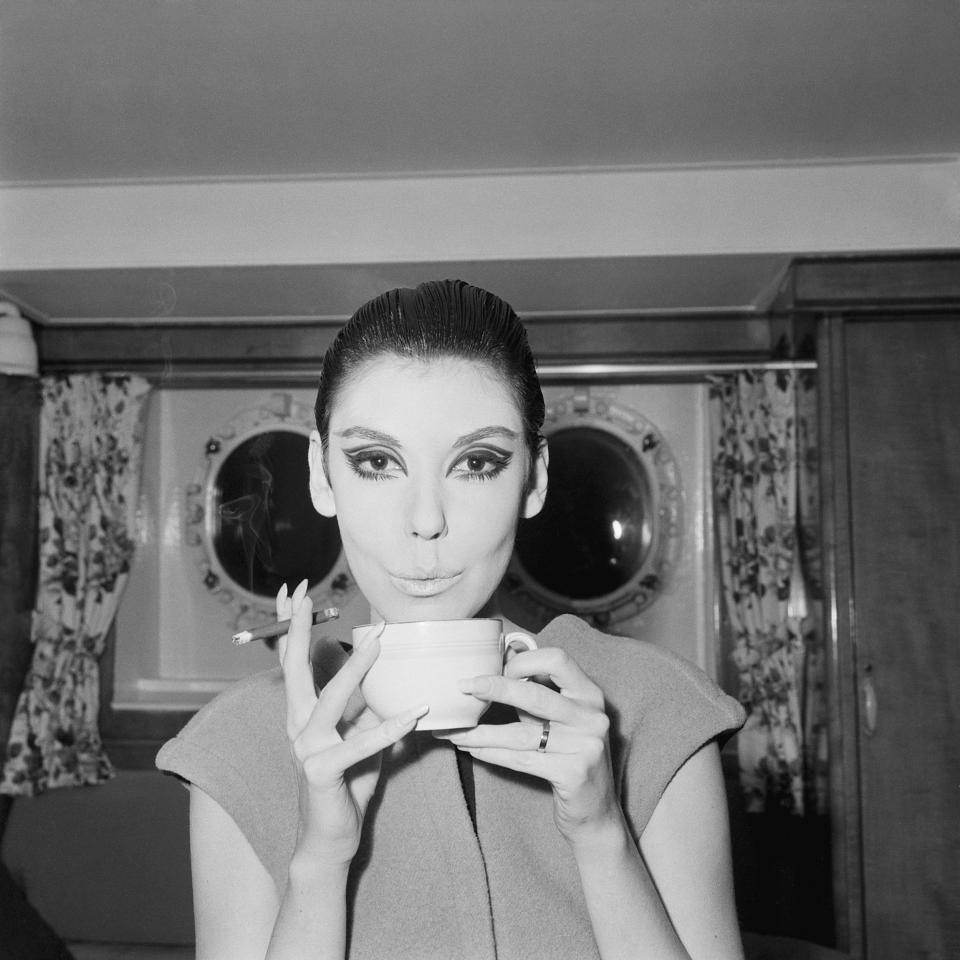

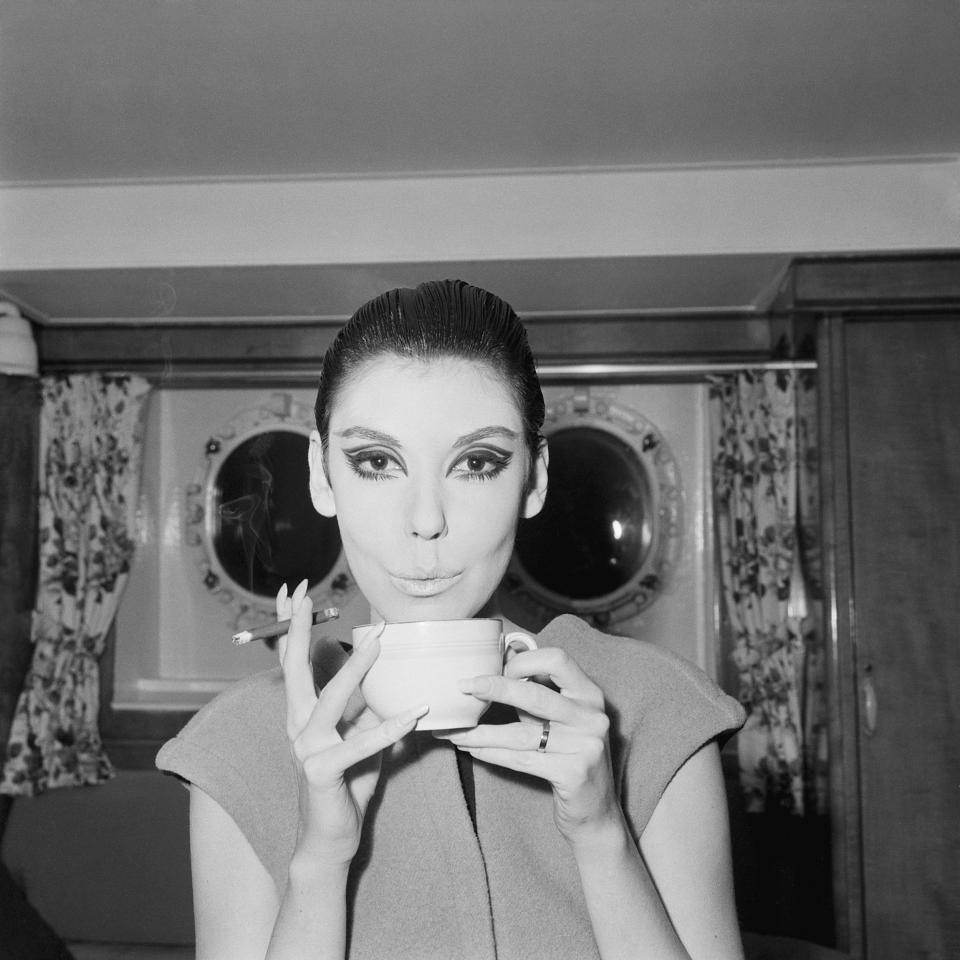

At times her relationship with Gernreich bordered on the symbiotic. He would make a collection like Pierrot and she would paint her face like a clown to match. While he was working on an Asian collection, she was in another part of the world, unaware of his plans, experimenting with Kabuki-like mask makeup. When he made a black skull with feathers, she plucked her eyebrows to give her face a look of death. “Rudi and I turned on each other… we fed each other,” she recalled.

She continued to wear his clothes in later life, wearing them to most public appearances. They included oversized florals, windowpane checks and vinyl-striped minidresses. Coupled with her moony locks, heavy-rimmed eye make-up and her signature Vidal Sassoon asymmetrical haircut – “Sassoon is to hair, what Picasso is to painting,” she once said – they made her one of the most iconic figures. recognized in fashion.

She became disillusioned with the industry as a whole, however, declaring it “dead” rather than “dream occasions” on the red carpet. Away from the party scene she was probably found in her garden, clad in jeans and a jumper.

Margaret Anne Moffitt was born in Los Angeles on 14 May 1940. Her father, Jack Moffitt, was a screenwriter and film critic, and she enjoyed a comfortable upbringing, attending the exclusive Marlborough School for Girls.

As a teenager, she had an after-school job at Jax, an avant-garde store in Beverly Hills popular with the likes of Joan Collins and Audrey Hepburn. It was here that she met Rudi Gernreich, who was already an established designer in the mid-thirties, and admired his clothes – even though he thought at the time that she was too young to be his model.

Instead, she went to New York for two years to study theater and ballet at the Neighborhood Playhouse. When she returned to Hollywood she got a few small roles in films such as Girls Town (1959) and the Korean war film Battle Flame (1959).

The first of the relationships that would define her career began when jazz photographer Bill Claxton came to photograph her then-boyfriend for a magazine called Eve. The three spent the next 16 hours together, and it was only a few months before Bill proposed. Gernreich attended the wedding, and soon after the designer collaborated with the couple on a series of fashion spreads.

Gernreich shot his signature photograph of Peggy Moffitt in Claxton’s living room, standing on a bath mat. At first, Life magazine refused to publish the picture, with the editor telling Claxton that “bare breasts are only allowed if the woman is aboriginal”.

The trio reposted the image with Peggy Moffitt’s hands covering her breasts, but she was unhappy with the result, as it meant “going along with the whole sassy, tease-y thing like a Playboy bunny”. In fact, Playboy offered her $17,000 (more than her annual salary) to print the topless image, but she rejected the proposal as “unbelievable”.

In later years Richard Avedon photographed her wearing Rudi Gernreich’s “no-bra bra”, an alternative to the rigidly structured contraptions of the era. She accompanied the designer to England to collect the Sunday Times international fashion award and stayed for a year, dividing her time between London and Paris.

She had a small role in Michelangelo Antonioni’s cult film Blow-Up and played a role model in Who Are You, Polly Magoo? (both 1966). Photographer Barry Lategan, who was responsible for launching Twiggy’s career, shot the two of them together, Peggy Moffitt cradling the younger model’s head.

When she returned to the United States, Peggy Moffitt starred in a publicity film (shot by Claxton) called Basic Black (1967), and Vidal Sassoon gave her the short hair she would keep for the rest of her life. Basic Black is now considered one of the first fashion videos ever made.

In December of that year she appeared with Gernreich and fellow model Leon Bing on the cover of Time magazine. The two women were his staunchest champions and critics, and Gernreich told one interviewer: “I only work with models I like and respect, and their reactions are extremely important to me.”

By the end of the decade, however, their wits had become so intertwined that Peggy Moffitt had begun to withdraw from the association, complaining: “I could put on a sack of flour and you’d think it was Gernreich. ” She refused to shave her body and face her “anti-statement” show in 1970, and in 1973 she withdrew from the fashion scene, moving back to LA for the birth of her son.

By the time Gernreich died in 1985 he had almost stopped designing, although the fashion world was still recognized as one of his most creative talents. In 1991 Peggy Moffitt and Bill Claxton published The Rudi Gernreich Book, which included a detailed photographic record of the various looks he created for her. She held the legal rights to her designs and drew them as inspiration in collaboration with Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons brand, which included a woolen “bikini” top.

Later in life Peggy Moffitt lived in the Hollywood Hills, where she furnished the white walls with photos from her modeling career as well as images shot by her husband Bill. The wardrobe was filled with Rudi Gernreich’s creations: jumpsuits, jackets, trousers and minidresses. There were ten crates of clothes in his store.

Bill Claxton predeceased her in 2008. They had a son, Christopher.

Peggy Moffitt, born 14 May 1940, died 10 August 2024