Every year I ask college students in the course I teach about the Black Death in the 14th century to imagine they are farmers or nuns or nobles in the Middle Ages. What life would they have in the face of this terrible disease that killed millions of people in a few years?

Putting aside how they imagine what it would be like to fight the plague, these undergrads often indicate that during the Middle Ages they would already be considered middle-aged or old people at the age of 20 . Apart from being at the forefront of life. thought they would soon be dead.

They reflect a common misconception that longevity in humans is a recent phenomenon, and that no one in the past lived much beyond their 30s.

But that is not true. I’m a bioarchaeologist, which means I study human skeletons excavated from archaeological sites to understand what life was like in the past. I am particularly interested in demography – mortality (death), fertility (births) and migration – and its connection to health conditions and diseases such as the Black Death hundreds or thousands of years ago. There is physical evidence that many people in the past lived long lives – just as some people do today.

Bones record longevity

One of the first steps in researching past demography is to estimate how old people were when they died. Bioarchaeologists do this by using information about how your bones and teeth change as you age.

For example, I am looking for changes in the joints in the pelvis that are common at older ages. Observations of these joints in people today whose ages we know allow us to estimate the ages of people from archaeological sites with similar joints.

Another way to estimate age is to use a microscope to count the annual additions of mineralized tissue called cementum on teeth. It is like counting the rings of a tree to see how many years it has lived. Using an approach like this, many studies have documented the existence of long-lived people in the past.

For example, by examining skeletal remains, anthropologist Meggan Bullock and her colleagues found that in the city of Cholula, Mexico, between 900 and 1531, most people who reached adulthood lived past 50 years. age.

And of course there are many examples from historical records of people who lived very long in the past. For example, the Roman Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century is reported to have died at the age of 83.

An analysis of the development of an ancient anatomically modern tooth Homo sapiens a person from Morocco suggests that our species has had a long lifespan for at least the last 160,000 years.

Clearing up a mathematical misunderstanding

Given the physical and historical evidence that many people lived long lives in the past, why does the misconception that everyone was dead by age 30 or 40 persist? It stems from confusion about the difference between individual lifespans and life expectancy.

Life expectancy is the average number of years of life left for people of a given age. For example, life expectancy at birth (age 0) is the average life expectancy of newborns. Life expectancy at age 25 is the longest people live on average since they have lived to the age of 25.

In medieval England, boys born into landed families had a life expectancy of only 31.3 years. However, life expectancy at age 25 for landowners in medieval England was 25.7. This means that people in that era who celebrated their 25th birthday could expect to live until they were 50.7, on average – another 25.7 years. Although 50 years old may not seem old by today’s standards, remember that this is an average, so many people would have lived much longer, into their 70s, 80s and even older.

Life expectancy is a population-level statistic that reflects the conditions and experiences of a wide variety of people with very different health conditions and behaviours, some who die at very young ages, others who live to be over 100 d ‘age, and many people who have their lives. spans fall somewhere in between. Life expectancy is not a promise (or a threat!) about the lifespan of any single person.

What some people don’t realize is that low life expectancy at birth for any population indicates very high infant mortality rates. That’s a measure of deaths in the first year of life. Given that life expectancies represent the average for a population, high death rates at very young ages will skew life expectancy calculations towards younger ages. But typically, many people in those populations who make it past the vulnerable years of infancy and early childhood can expect to live relatively long lives.

Advances in modern sanitation – which reduce the spread of diarrheal diseases that kill infants – and vaccinations can greatly increase life expectancy.

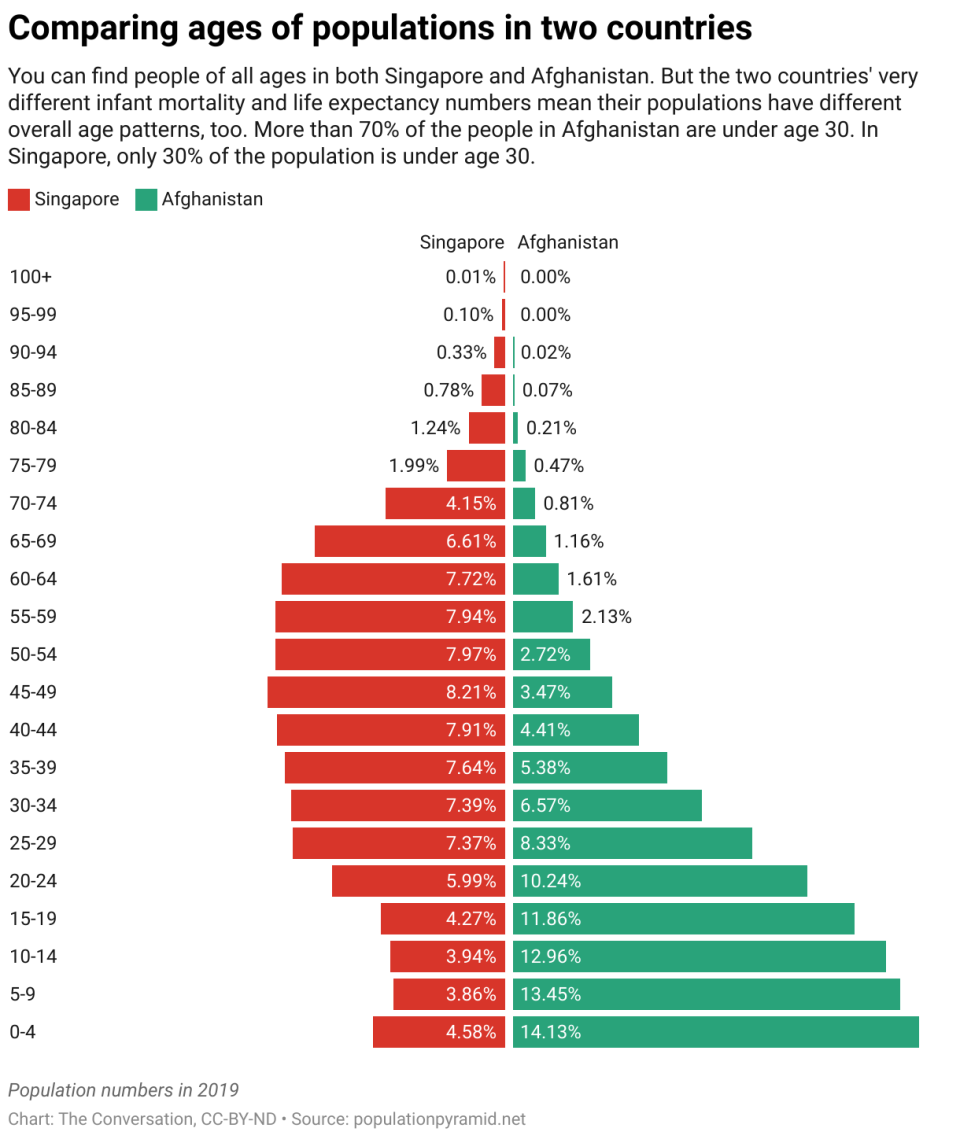

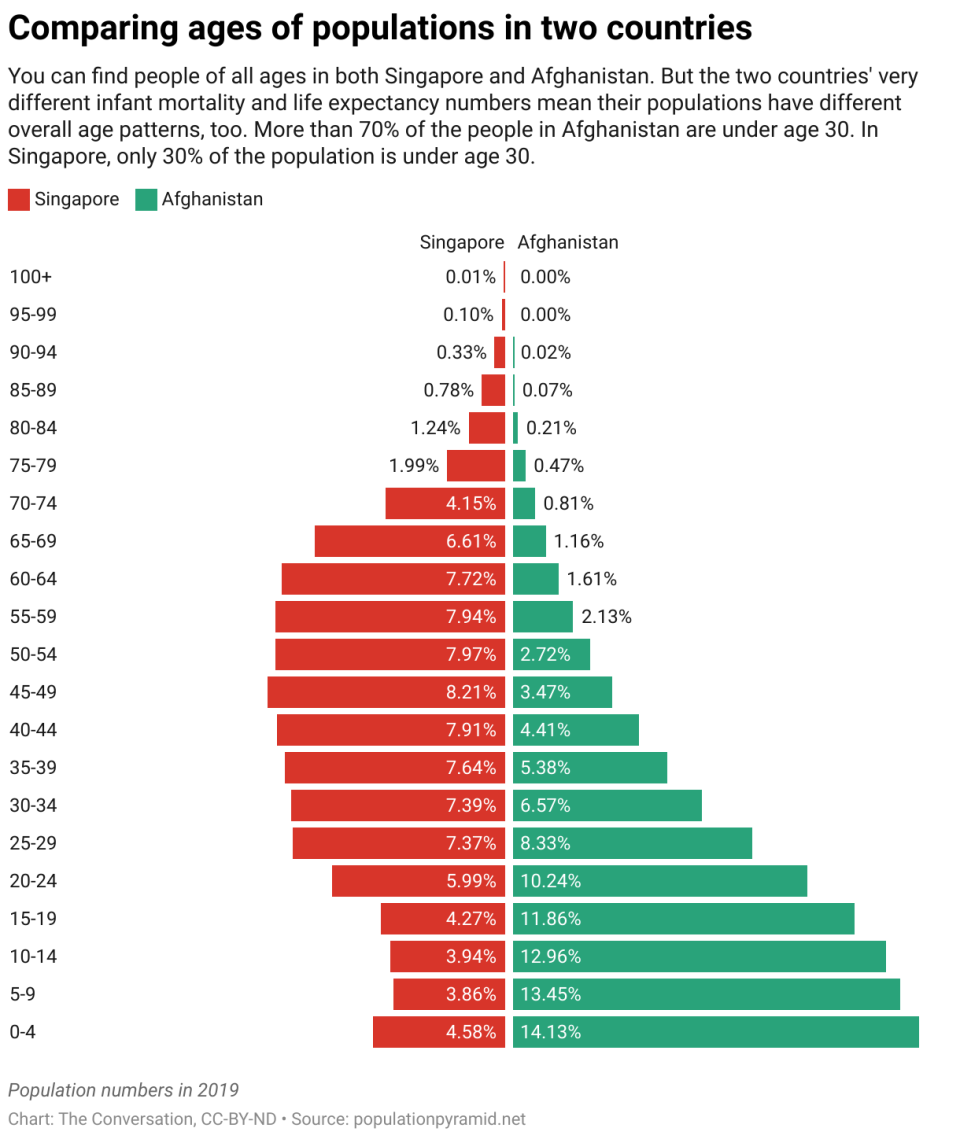

Consider the effect of infant mortality on overall age patterns in two contemporary populations with very different life expectancies at birth.

In Afghanistan, life expectancy at birth is low, at just over 53 years, and infant mortality is high, at nearly 105 deaths for every 1,000 children born.

In Singapore, life expectancy at birth is much higher, at over 86 years, and infant mortality is very low – less than two babies die for every 1,000 births. In both countries, people live to a very old age. But in Afghanistan, because many more people die at very young ages, proportionally fewer people live to old age.

It is possible to live a long life

It is wrong to see long lives as a significant and unique characteristic of the “modern” era.

Knowing that people often lived long lives in the past may make you feel more connected to the past. For example, you can imagine multi-generational families and gatherings, with grandparents in Neolithic China or Medieval England bouncing their grandchildren on their knees and telling them stories about their own childhood decades earlier. You may have more in common with people who lived long ago than you realized.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Sharon DeWitte, University of South Carolina

Read more:

Sharon DeWitte receives funding from the National Science Foundation.