Valentine’s Day will not be the heart and flower of some “kissing stars” – or, in other words, the stars that exist in a close binary locked in a waltz that left one a daffodil, the other a swollen orb . .

Astronomers have zoomed in on a group of such “odd couple” stars, only to find that the bodies appear to have been created by a violent and cannibalistic interstellar feeding process. How unromantic.

The team, led by Georgia State Postdoctoral Research Associate Robert Klement, used the Center for High Angle Astronomy (CHARA) telescope array to study spinning stars known as B-line emitting stars, or Be stars, at watch faint light patterns coming from orbiting tiny. stripped stars, called “subdwarfs.”

Related: A dead ‘vampire’ star is feeding on a companion and firing cosmic cannonballs

Exploring these massive stars with the CHARA Array telescopes has revealed how both subdwarf and Be stars are formed, shedding light on the long-mysterious world of binary stars.

“The CHARA Array survey of Be stars has shown directly that these stars were formed by wholesale transformation through mass transfer,” said Douglas Gies, CHARA Array director, in a statement. “We are now seeing, for the first time, the result of the stellar festival that brought the stripped stars.”

When binary stars get too close

Stars are believed to be formed as a result of intense interactions between stellar partners in very close binary systems, especially when one of those stars is particularly massive.

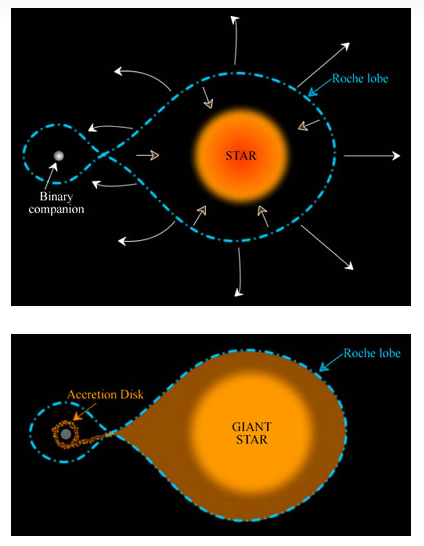

Binary systems contain stars in mathematically defined contiguous pear-shaped “lobes” called Roche lobes. As massive stars age, they can expand and fill in their Roche lobe. When this happens, the stars begin to “kiss” as material from the “donor star” fills a lobe on to the other. This stellar material passes through a central point where the brackets meet, and forms a disk around the host star, known as an accretion disk, from which material gradually falls to the surface of the star.

This mass transfer, cannibalistic process continues until the donor star has been stripped of almost all of its outer plasma layer, transforming into a tiny hot core: A subdwarf star.

This is not the only consequence of the feeding process, however. Material removed from the donor star has angular momentum, a force that is also imparted to the cannibal star.

This accelerates the rotation of the feeding star, and means that these stars turn very quickly. In fact, Be giant stars are some of the fastest stars ever seen; some rotate so rapidly that they eject matter from their equators. Over time, this material even manages to collect in a disc around them.

The stripped subdwarf stars that fed Be stars are difficult to see in their destroyed state because they are so close to these massive stars. Their faint emissions are overwhelmed by the bright emissions of their cannibalistic counterparts.

The six telescopes of Georgia State’s CHARA Array on the summit of Mount Wilson allowed the astronomers to see these narrow, striped stars because, because these scopes act together as a single 330-meter-wide telescope, they can separating the light from the binary stars even when the stars are extremely close together.

The team also used the MIRC-X and MYSTIC cameras, built at the University of Michigan and the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, which can record both faint and bright light emissions from nearby objects.

The aim of this two-year investigation was to find out whether the transfer of matter to the Be star accelerated their rotation.

About nine of the 37 Be stars studied by the team indicated that the stripped stars have a weak light characteristic. The team completed seven of these targets to achieve the orbits of these components in better orbits around the most massive stars Be. This showed how intense the feeding process is that creates these very different stars.

“The orbits are important because they allow us to determine the mass of the star pairs,” Klement said. “Our mass measurements indicate that the stripped stars lost almost everything. In the case of the star HR2142, the stripped star probably went from 10 times the mass of the Sun down to about one solar mass.”

Related Stories:

— Very Large Telescope surprised to discover exoplanet lurking in 3-body star system

— Some mysterious ‘fast radio bursts’ may erupt from two-star systems

— Scientists observe the first gamma-ray eclipse from a strange ‘spider’ star system

Not every Be star targeted by the team appears to be orbited by a torn sub-black star, however, as the team suspects that this is because these missing stars have evolved into white dwarfs and are far too faint to see now.

Klement will extend the search for these odd couples of small and large stars to the southern horizon over Earth using the Very Large Telescope in the Atacama Desert in Northern Chile. It will also turn to the Hubble Space Telescope to further examine ultraviolet light from the hot subdwarfs.

“This survey of Be stars—and the discovery of nine faint companion stars—truly demonstrates the power of CHARA,” said Alison Peck, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Astronomical Sciences, which supports the CHARA Array. “Using the array’s exceptional angular resolution and high dynamic range we can answer questions about star formation and evolution that have never been answered before.”

The team’s research was published in February in The Astrophysical Journal.