Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Long before the first sharks appeared, large predatory worms were “beasts of terror” in the seas more than 500 million years ago, according to new research.

Scientists have discovered fossils of a previously unknown species of worm during an expedition in North Greenland, revealing what they believe to be the earliest carnivorous animals.

The worms reached nearly 1 foot (30 centimeters) in length and were some of the largest swimming animals of the time, known as the Early Cambrian Period.

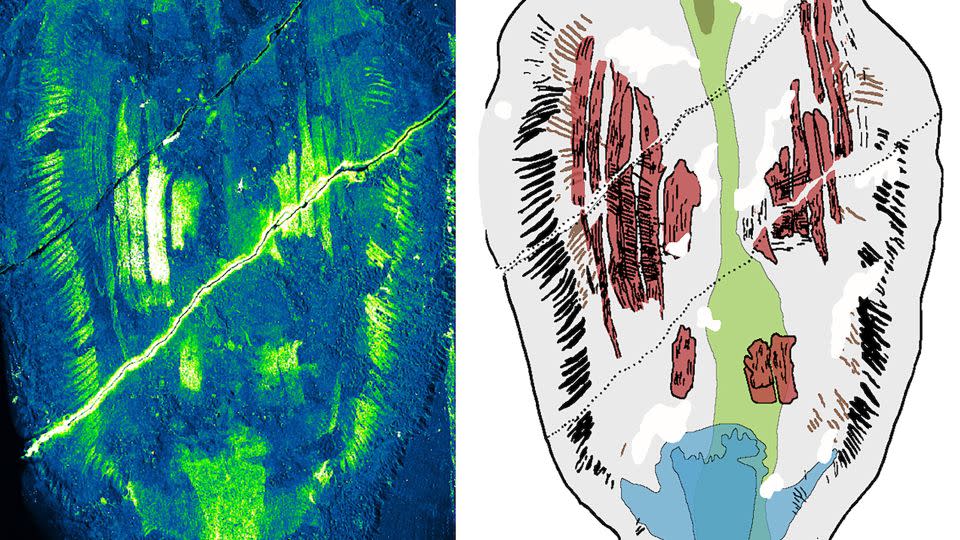

The researchers named the worms Timorebestia, Latin for “beasts of terror.” Fins marched down the sides of their bodies, and their distinctive heads had long antennae and huge jaws.

Previously, primitive arthropods, including strange-looking distant relatives of crabs and lobsters called Anomalocaris, were believed to be at the top of the marine food chain during the Cambrian Period, which lasted from 485 million to 541 million years ago. since then.

But the predatory worms were such an integral part of the ecosystem 518 million years ago that scientists didn’t even know they existed until they found the fossils. A study describing the results was published on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

“Timorebestia were giants of the day and would have been near the top of the food chain,” said senior study author Dr. Jakob Vinther, associate professor of macroevolution in the University’s Schools of Earth and Biological Sciences. Bristol, in a statement.

“That’s comparable in importance to some of the top carnivores in the modern oceans, like sharks and seals back in the Cambrian period,” Vinther said. “Our research shows that these ancient ocean ecosystems were quite complex with a food chain that allowed several layers of predators.”

During the Cambrian Period when carnivorous predators appeared, “animals grew explosively for the first time,” Vinther said. “It had a tremendous impact on the carbon and nutrient cycles as well as the pace of evolution.”

Tracing an evolutionary path

These predatory worms are distant relatives of the much smaller modern arrowworms, or chaetognaths, which feed on zooplankton, Vinther said.

Arrowworms are considered to be among the oldest animals to have appeared in the Cambrian Period. Arthropods first appeared between 521 and 529 million years ago, and evidence of arrowworms suggests their existence as early as 538 million years ago.

“Both dartworms were swimming predators, with the more primitive Timorebestia,” Vinther said. “So we can think that before arthropods arose, they were probably the biggest predators in the oceans. They may have had a dynasty of about 10-15 million years before being replaced by other and more successful groups.”

Preserved within the fossilized digestive system of Timorebestia was Isoxys, a swimming arthropod with long, protective spines pointing forward and backward.

“It is clear, however, that they were not entirely successful in avoiding that fate, as they were severely affected by Timorebestia,” study co-author Morten Lunde Nielsen, a former doctoral student at the University of Bristol, said in a statement.

Finding information about Timorebestia provides insight into the evolutionary timeline of worms from half a billion years ago to the present day, the researchers said.

“Today, arrowworms have threatening bristles on the outside of their heads to catch prey, but Timorebestia has jaws inside its head,” study co-author Luke Parry, associate professor of paleobiology at the University of Oxford, said in a statement.

“This is what we see in microscopic jawworms today – organisms that we shared with arrowworms more than half a billion years ago. Timorebestia and other fossils like it provide links between closely related organisms that look very different today.”

Modern arrowworms have a unique nervous system on their abdomen called a ventral ganglion, which was also found to be conserved in Timorebestia, said senior study author Dr. Tae-Yoon Park, chief research scientist at the Korea Polar Research Institute. The nervous system was also seen in another fossil called Amiskwia, suggesting that a soft-bodied animal is also evolutionarily related to arrowworms.

A remote but rich fossil deposit

Park led a research team on expeditions to Sirius Passet, a well-preserved fossil site in the northernmost reaches of Greenland. The sun shines all day in the remote location, which is 600 miles (966 kilometers) from the North Pole, Vinther said. Researchers have a small window of about six weeks each year when the site is accessible, but the trek is worth it, he said.

“The fossils are so dense here, compared to any other area, that every time you split the rock you expose hundreds of soft fossil organisms,” Vinther said.

Members of the research team are keen to return to Sirius Passet, where they found fossilized remains of other relatives of Timorebestia, to better understand the first food chain in the ocean.

“Thanks to the amazing, exceptional preservation in Sirius Passet we can also reveal exciting anatomical details including their digestive system, muscle anatomy and nervous systems,” said Park. “We have many more exciting results to share in the coming years that will help reveal how the earliest animal ecosystems looked and developed.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com