-

Until recently, the consensus was that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were separate species.

-

But most people carry about 2% of Neanderthal DNA, challenging the notion that we are different.

-

Other studies suggest that Neanderthals were not inferior to Homo sapiens and should be considered as humans.

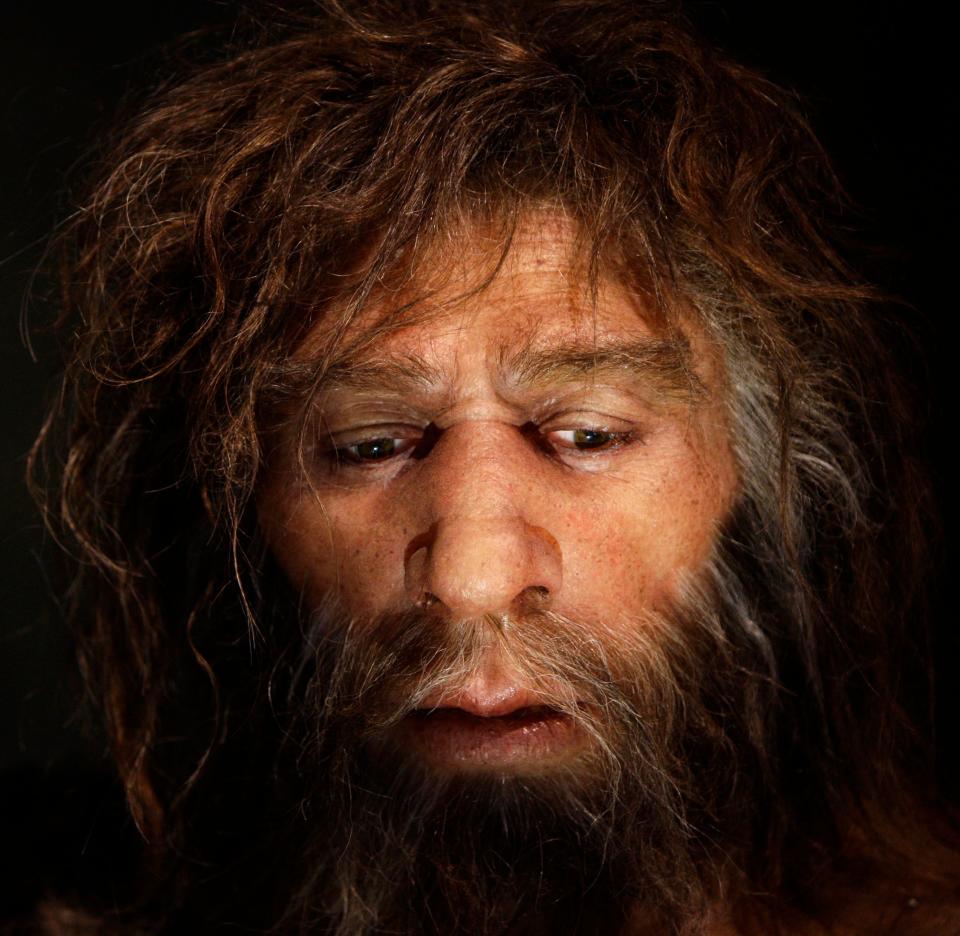

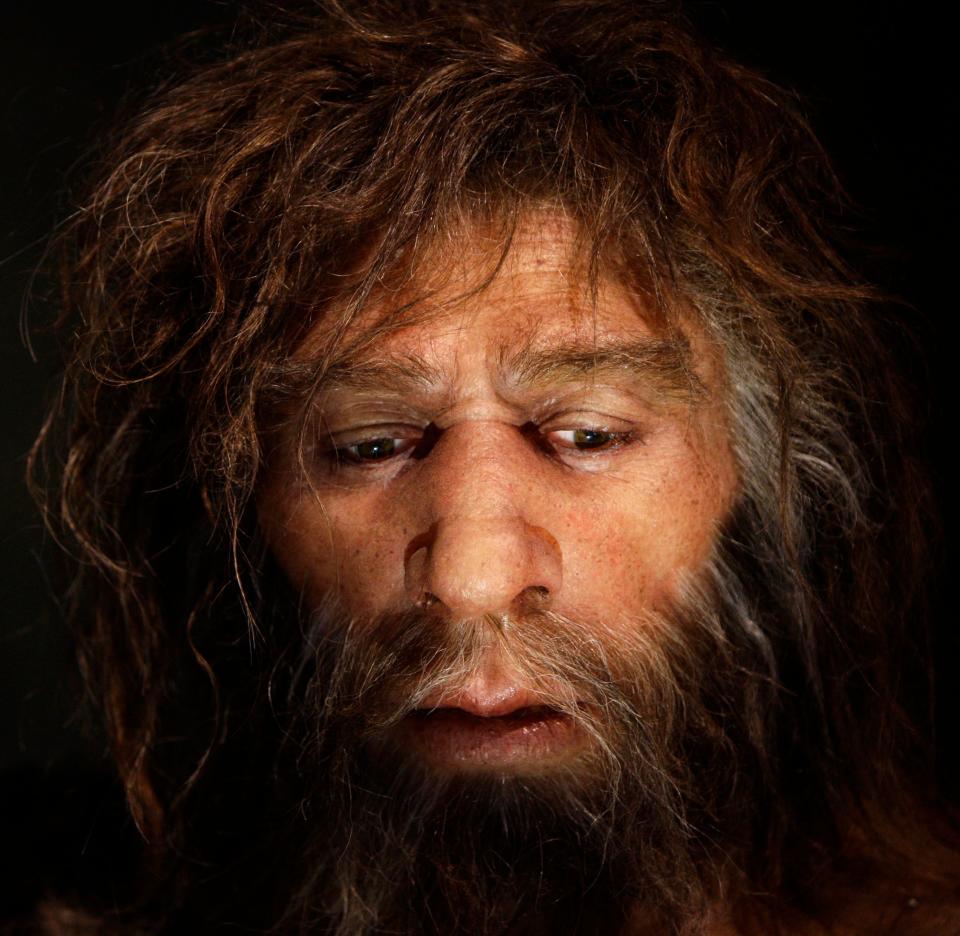

Neanderthals have long been portrayed as weak-witted, brutish monsters who were genetically inferior to our direct ancestors, early modern humans.

These monkey-like creatures spoke while crying, were plagued by illnesses, and died 40,000 years ago after losing the evolutionary battle against Homo sapiens.

Or at least, that’s what we’ve been told. Recent discoveries, however, are challenging that view and starting a debate among scientists about whether Neanderthals should be considered the same species as modern humans.

If Neanderthals were our species, it could reshape the history of human evolution and challenge how we define what makes us human.

Most of us have some Neanderthal DNA

The first fossils of Neanderthals were identified almost 200 years ago. By now, you’d think scientists would have made up their minds as to whether they should be defined as a separate species from Homo sapiens.

But this turned out to be a hotly debated topic, Antoine Balzeau, a paleontologist from the National Museum of Histoire Naturelle in France, told Business Insider.

“When we were first discussing the fossils in the 19th century, there was no real debate about specific species or not, simply because at the time, humans were seen as a species but by default,” he said. .

As more fossils emerged, scientists began to question the strict separation between the species.

Still, until recently, the consensus was largely that Neanderthals should be considered separate. The hominins, who roamed Europe as early as 430,000 years ago, were only briefly in contact with Homo sapiens who came from Africa, who reached Europe around 50,000 years ago.

The lineages diverged about 500,000 years ago—recently in the history of human evolution, but long enough ago that they looked remarkably different. For many, that evidence was enough to close the debate: Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were separate species.

That view changed in 2008 when Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo achieved something thought impossible: he sequenced the Neanderthal genome by extracting DNA from ancient bones.

Through his research, Pääbo was able to show that there is a bit of Neanderthal in most of us. In fact, he showed that most people carry the living around 2% of Neanderthal DNA.

The evidence also suggests that the ancestors of humans and Neanderthals probably had children together when they coexisted around 50,000 years ago.

This news created a dogmatic split, opening up the possibility, once again, that Neanderthals and humans should be considered the same species.

After all, according to the strict biological definition of species, animals from different species should not be able to produce fertile offspring.

“It was definitely a big game changer at that point,” Laura Buck, an evolutionary anthropologist studying hybridization between hominin species, told BI.

“I think it brought that discussion to the fore again,” she said.

Were Neanderthals more numerous than our distant cousins?

The idea that species can’t reproduce is “intuitively appealing because it’s kind of clear cut,” Buck said, “but the biology is not clear.”

She cites several examples of mammals that are known to interbreed and have fertile offspring, such as wolves and dogs, despite being clearly defined as separate species.

For her, a better definition of Neanderthals, the most tried and tested scientifically, is the first: the characteristics of their bones separate them from modern humans and their direct ancestors.

“I know that there are different papers saying that if you shaved a Neanderthal, put him in a suit, and put him on the tube or the subway in New York, nobody would notice, I don’t think so that’s true,” she said. .

“I think we would definitely think they looked a little strange,” she said.

Balzeau agrees. “There may be some discussion between specialists about how we define the different groups but from a paleontological point of view, Homo neanderthalensis and almost Homo sapiens have very clear anatomical differences,” said Balzeau.

For others, however, the genomic information should be another argument for liberating the Neanderthal from its drawn-out stereotype.

That’s the case for Paul Pettitt, an archaeologist who specializes in the Paleolithic at Durham University in the UK.

“It would be a guess to use that evolutionary diversity to assume that there are different species,” he told BI.

Can culture define species?

In the last twenty years, excavations have begun to emerge showing that the Neanderthals may have been much more sophisticated than previously thought.

Pettitt counts himself among those who, until recently, were skeptical that Neanderthals could have any sense of sophistication.

“Until say 20 years ago, Neanderthal behavior was seen as quite stupid, or at least quite limited, and Homo sapiens, in contrast, appeared as Shakespeare mentioned, dancing around the Europe,” he joked.

“What is, of course, nonsense, but it is very forgotten entrenched,” he said.

After all, relative to their size, some studies suggest that the brains of Neanderthals were at least the same size, if not larger, than our ancestors, indicating that they may have been very cerebral, said Pettitt.

“You don’t buy a super computer to use as an alarm clock. There’s an evolutionary reason why Neanderthals chose this metabolically expensive tissue,” he said.

Studies have shown that Neanderthals were skilled hunters, and hidden workers, who created rudimentary jewelry, had a complex lithic industry, and even worked with pigment.

Some scientists even believe that they may have had some form of spirituality, and that they would bury their dead lions, revery, and may have even created cave paintings — although that evidence is still a matter of debate.

For Pettitt, this suggests that because Neanderthals and humans lived side by side in Europe, there was a good chance that they shared a culture or learned from observing each other.

If they spoke, he said, “we can assume that they probably spoke different languages. But that similarity suggests that there really was a shared meaning, however simple.”

Could Neanderthals be called human?

There is a bigger picture question here: should Neanderthals be considered human?

“What humanity is really about depends on the group of people you’re talking to,” Buck said.

“It’s something that’s culturally defined, but it’s also something that has sort of value judgments. We talk about inhumanity. We talk about humanity. It’s not something that only refers to different types of organisms,” she said.

With the large number of people alive today, it could be argued that there is more Neanderthal DNA on Earth than ever before.

Angela Saini, author of “Superior: the Return of Race Science,” argues that there is a real danger of getting this wrong. Those who are thought to have more Neanderthal DNA today could be wrongly thought of.

Early studies linked these Neanderthal genes to modern health effects such as autoimmune diseases, diabetes, and some cancers – although the direct impact of these genes on the health of the person who carries them remains largely unclear. Neanderthal genes were also significantly associated with contracting COVID-19.

As East Asian populations have been found to carry slightly more Neanderthal DNA on average, there is a risk that this information will be used for discrimination.

The flip side is that our interpretation of Neanderthal culture has changed dramatically in recent years. Saini notes that the Neanderthal image was rehabilitated just as humans began to draw closer to European populations, and genetic information began to suggest that they were fairer-skinned with red hair.

“That’s what I find particularly interesting. A century ago, the supposed similarity between Neanderthals and Aboriginal Australians was used as a justification to pull modern living people out of the circle of humanity,” she told WNYC.

“Now, because we see that Neanderthals have some relationship with the Europeans of today, the Neanderthals themselves are an extinct species into that circle of humanity.”

Rewriting our history

We are still in the process of understanding the Neanderthals and our relationship with them. As we begin to unpack the history of human and Neanderthal evolution, scholars’ decision to separate the two and portray one as superior is being re-scrutinized.

When he revealed his research, Pääbo reflected on how people living on Earth today are quite exceptional – not necessarily because Homo sapiens are inherently superior, but because there is not much time in the history of human evolution when Homo sapiens was the only hominin or human on the planet.

“If Neanderthals and Denisovans lived, how would we deal with that today?” said Pääbo.

“Would we have even worse racism against them than we experience among us today – because they were very different in some ways – or could we think differently and say that if they were here today they wouldn’t would we only have one type of people?” he said.

“I think both things are possible and it kind of reflects our opinion of people and how we speculate about that.”

Read the original article on Business Insider