As NASA debates the the safety of the Boeing Starliner spacecraft after multiple helium leaks and thruster issues, the agency is “getting serious” about a backup plan to bring the ship’s two crew members back to Earth aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon, officials said Wednesday.

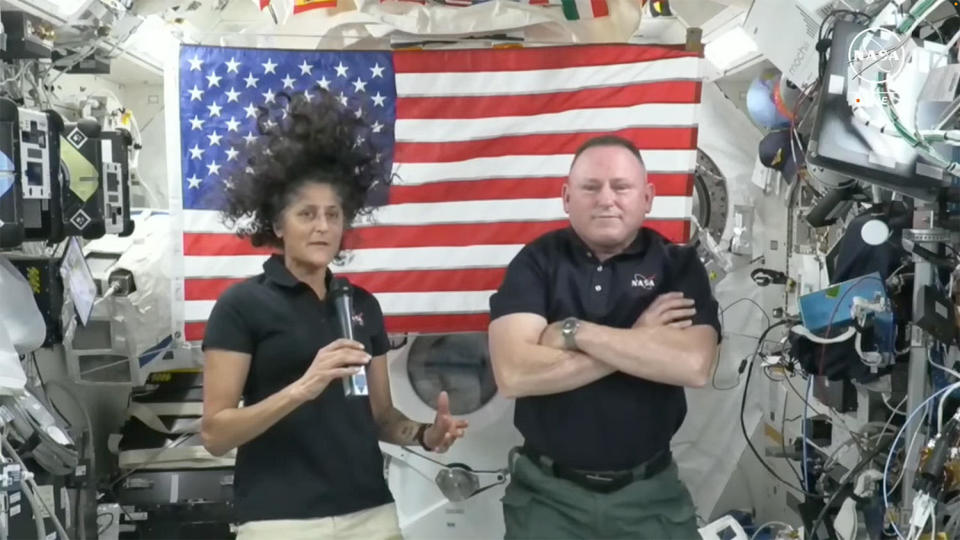

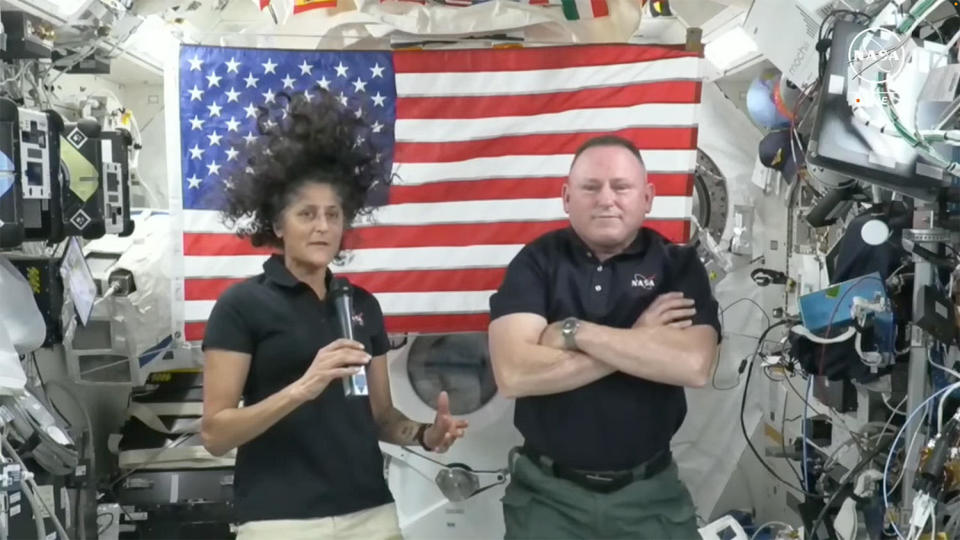

In that case – and no final decisions have been made – Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams would stay aboard the International Space Station for another six months and come down on Crew Dragon scheduled to launch on September 24 to transport longtime crew members to the outpost.

Two of the four “Crew 9” astronauts already assigned to the Crew Dragon flight would be pushed from the mission and the ship would launch with two empty seats. Wilmore and Williams would return to Earth next February with the two Crew 9 astronauts.

Shortly before Crew Dragon’s launch, the Starliner would launch from the station’s home port and return to Earth under computer control, with no astronauts on board. The Crew Dragon would then dock at the empty forward port.

Two earlier Starliner test flights were flown unmanned and both landed successfully. The current Starliner computer system would have to be updated with fresh data files, and flight controllers would have to improve procedures, but that work can be done in time to support a mid-September return.

If that happens, Wilmore and Williams would be spending 268 days — 8.8 months — in space instead of the week or so they planned when they blasted off on the United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket on June 5.

Based on uncertainty about the exact cause of the thruster problems, “I would say that our chances of an uncrewed Starliner return have increased slightly based on where things have gone in the last week or so,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA director. space operations.

“That’s why we’re looking more closely at that option to make sure we can handle it.”

But he cautioned that no final decisions about when — or how — to bring the Starliner crew home will be made until the agency completes a high-level flight readiness review.

No date has been set, but it could happen late next week or the week after.

“Our main option is to get Butch and Suni back on Starliner,” said Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. “However, we have done the necessary planning to make sure we have other options open. We are working with SpaceX to make sure they are ready to (return) Butch and Suni on Crew 9 if we need that.

“Now, we haven’t approved this plan (yet). We’ve done all the work to make sure that this plan is there … but we haven’t turned that into a formality. We wanted to make sure that we had all that flexibility in place.”

Before the launch of the Starliner, NASA and Boeing engineers knew of a small leak of helium in the spacecraft’s propulsion system. After ground tests and analysis, the team concluded that the ship could be safely launched as is.

The day after launch, however, four more helium leaks occurred and five maneuvering triggers on their way failed to operate as expected. Since then, NASA and Boeing have been conducting data reviews and ground tests to try to understand exactly what caused the two issues.

The Starliner uses pressurized helium to push propellants to the thrusters, which is critical to keeping the spacecraft properly oriented. That is especially important during a de-orbit braking “burn” using larger rocket engines to slow the ship down to re-enter and land on the target.

To clear the Starliner for a piloted return to Earth, engineers must develop an acceptable “flight rationale” based on test data and analyzes that provide confidence that the ship can make it through reentry and landing with the required level of safety. .

“The Boeing team is very optimistic that the vehicle could get the team home right now with the uncertainty we have,” Bowersox said. “But we have other people who are probably a little bit more conservative. They worry that we don’t know for sure, so they consider the risk higher and would recommend that we avoid coming home (on Starliner) because we have another option.

“So that’s part of the discussion we’re having at the moment. But again, I think both views are reasonable with the band of uncertainty we have, so our effort is trying to reduce that uncertainty. “

Boeing insists that the Crew Dragon backup plan is not needed and that tests and analyzes of helium leaks in the Starliner propulsion system and initial trouble with maneuvering thrusters show that the spacecraft has more than enough margin to return Wilmore and Williams safely to Earth.

The helium leaks, Boeing says, are understood not to have deteriorated and there is more than enough of the pressurized gas on board to push propellants to the thrusters needed to maneuver and stabilize the spacecraft through the brake jet. -critical orbit to drop off. orbit for re-entry and landing.

Likewise, engineers believe they now understand what caused a handful of painful maneuvering jets to overheat and catch fire during a lower-than-expected descent to the space station, leading them to the Starliner’s flight computer to be shut down during the approach.

Ground tests of a new Starliner thruster, fired hundreds of times under conditions that mimicked the experience of those aboard the spacecraft, replicated the overheating signature, likely caused by multiple burns during manual control system tests the capsule during extended exposure to direct sunlight.

The higher-than-expected heating likely caused small seals in thruster valve “poppets” to deform and expand, the analysis shows, reducing propellant flow. The thrusters aboard the Starliner were tested in space under normal conditions and all worked properly, indicating that the seals had returned to a less worn shape.

New procedures are in place to prevent the overheating that occurred during the rendezvous. An additional manual test shot has been ruled out, no extended exposure to the sun is planned and departure from the station requires less frequent firing compared to a rendezvous.

In a statement Wednesday, Boeing said, “We still believe in Starliner’s capabilities and its flight rationale. If NASA decides to change the mission, we will take the necessary steps to configure Starliner for an uncrewed return.”

The helium plumbing and thrusters are located in the Starliner service module, which is jettisoned to burn up in the atmosphere before the crew capsule comes back for landing. Therefore, engineers will never be able to examine the hardware to prove, with certainty, what happened.

At this point, that uncertainty seems to support returning Wilmore and Williams to Earth aboard the Crew Dragon. But he is not sure yet.

“If we could replicate the physics in some offline testing to understand why this poppet is heating up and extruding and then why it’s contracting, that would give us more confidence to go ahead, Butch and Sonny to return this vehicle,” Stich said.

“That’s what the team is really trying to do, to try to look at all the details and see if we can get a good physical explanation of what’s happening.”

Meanwhile, the wait for a decision drags on, one way or the other.

“In the end, someone — one more person — is designated as the decision maker, that person has to come to a conclusion,” Wayne Hale, a former shuttle flight director and program manager, wrote in a blog post earlier this week.

“The engineers will always always always ask for more tests, more analysis, more time to get more information to be more sure of their conclusions. The decision must also be made when done enough. The rub in all of this … is that it always involves risk to human life.”

Hale concluded his post by saying: “I don’t envy today’s decision makers, the ones who weigh flight reasoning. My only advice is to listen thoroughly, ask questions effectively, ask for more details when necessary . But when the time is there, a decision must be made.”

Murder victim’s girlfriend: “Look who you’re with”

James Rackover is bragging that he will beat the charges in phone calls from prison

Rep. Cori Bush loses congressional primary, 2nd progressive member of “Squad” to lose re-election