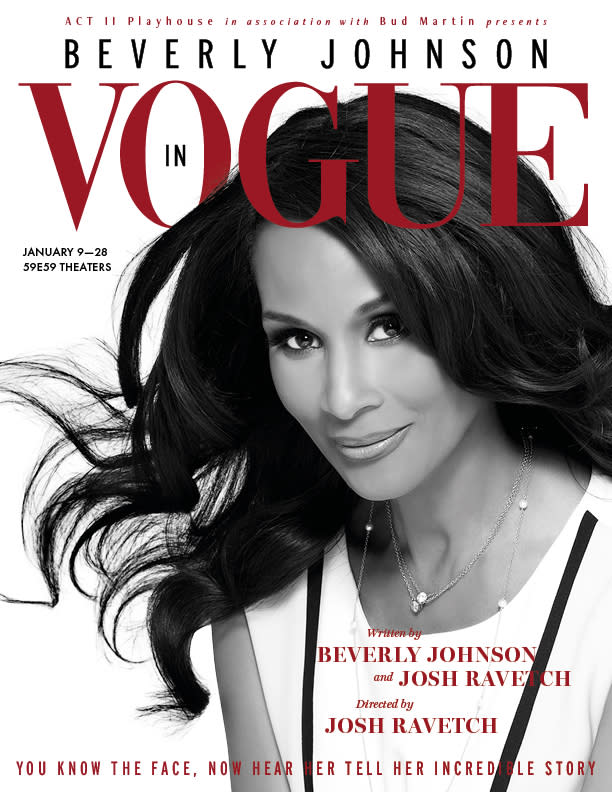

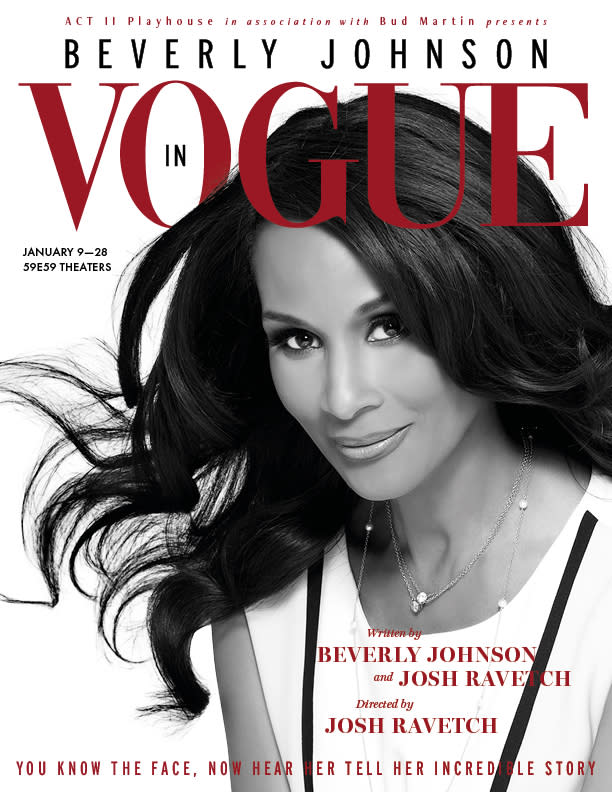

Fifty years after Beverly Johnson became the first Black model to land the cover of Vogue, she is still charging ahead through business, entertainment and diversity advocacy.

Her work and challenges are reflected in a one-woman show that just opened at Theaters 59E59 in New York. Running through January 28, “Beverly Johnson in Vogue,” explores her struggles and allegations of substance abuse against Bill Cosby, who released a defamation against her in 2016. After the murder of George Floyd, Johnson suggested that fashion , beauty and media. corporations interview at least two Black professionals for each job opening. (The concept was proposed by her partner Brian Maillian and is a derivative of “The Rooney Rule,” an affirmative action initiative enacted by former Pittsburgh Steelers chairman Dan Rooney in 2002.)

More from WWD

During an interview on Monday, Johnson was direct, but self-effacing and easygoing, describing some of the most memorable moments of her life and describing the fashion industry. In addition to running a beauty business through Beverly Johnson Enterprises, licensing deals and speaking engagements, she appears periodically on “The Barnes Bunch,” the reality show starring her daughter Anansa Sims, the fiancé of the ESPN analyst. Matt Barnes, and six children. “I’m Mary Poppins – I pop in, and I pop out,” she said.

Growing up “an introvert, an academic and a competitor on the first all-Black swim team,” Johnson said she hoped for a career in law while studying at Northeastern University. She had seen her on the cover of the Civil Rights movement with her “news junkie” father. It also influenced her perception of diversity. While in the army, Johnson’s father picked up four languages. Although he worked full time as a steel worker, he did his friends’ taxes from the family kitchen table for no fee. “A Polish friend would come in with a string of Polish sausages on his shoulder to take my father to do his taxes. An Italian friend would suggest something else. I got that kind of outlook on life from my father,” she said. “They would come in the back door even though we lived in an all-white neighborhood. It was like the roles were reversed. We used to go in the back door. They were friends too. It gave a very beautiful understanding of the diversity and love that people have,” she said.

He parlayed the strength required for competitive swimming—never mind the walks home from practice with wet hair (hand dryers weren’t yet a thing) in the frigid Buffalo winter—into his later professional modeling. “I was going to be a lawyer. I’m an introvert and a nerd. I was on the honor roll. Every time I would walk across the stage [to be honored], everyone would take me. I was the first Black cheerleader. I started the first Black student union,” she said. “I wasn’t pretty. There were girls who were quite short with big legs and figure. I was tall, thin and flat-chested. I wore my hair in two braids throughout high school. Nobody was chasing me,” Johnson said.

Interested in AI and engaging with a range of generations, Johnson said, “I don’t call it getting old. I call it ‘pro-aging,’ It’s like a treasure hunt.”

Johnson wrote the one-woman show a few years ago with playwright Josh Ravetch, whose credits include “Wishful Drinking,” “Onward: The Diana Nyad Story” with Carrie Fisher and “Step in Time! Music Memorial.” Before the pandemic came out, Johnson’s show was well received at a workshop in West Hollywood, she said.

Discussing how to celebrate the 50thth the anniversary of the Vogue cover was hard to count. “That’s half a century. It’s hard to even tell sometimes,” Johnson said.

Johnson said she has no idea why the cover happened (under the editorial supervision of Grace Mirabella.) “I honestly think it was a fluke. In those days, you didn’t know if you got the cover until you were on the cover,” she said.

She was hired in the spring of 1974 for a beauty shoot with photographer Francesco Scavullo, stylist Frances Stein, hair stylist Suga and Way Bandy handling the makeup. “There was definitely magic in the air. But there was magic in a great beauty shot,” Johnson said. “Somebody got the guts [to use the image for the history-making cover].”

Recalling the backlash and being interviewed by media “from all over the world,” Johnson said she only recently learned that Vogue reportedly did three production runs to keep up with demand. Resharing that and other personal stories including stories of adversity can make people think “if she can do it, I can do it,” Johnson said.

A gentleman was indirectly praised by “Beverly’s Full House,” which aired on the Oprah Winfrey Network, celebrating the cover of Vogue “to give him that moment in history that he deserves”. “You know how it is, you don’t want to blow yourself up – you want someone else to do it. But a closed mouth is never fed,” she said. Despite always speaking out about tougher topics like depression, hysterectomies and menopause, focusing on her fashion milestone was a new connection.

Substance abuse and addiction are also addressed in the off-Broadway show with Johnson, who cited the recent death of actor Matthew Perry (through the acute effects of ketamine) as an example of “how offensive the disease is now.”

“Recovery is sacred. What we learn in AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] that is it is not through promotion. It is three examples. They feel that you should not present it to the public. I’m still in AA so I followed the rules. Once in a while he went out. If someone asked me for a drink, I’d say, ‘I never drink or do drugs.’ They would say, ‘Huh, excuse me?’” she said.

Her audience is “laughing with me, crying with me,” she said.

Regarding the progress made by the fashion industry since the murder of Floyd in 2020, Johnson said that there has been some movement in appointing Black executives to corporate boards, but that there is work to be done. “We have a long way to go. Every industry is a bubble in itself, but ours is a tough little bubble to get into,” she said.

In terms of improving diversity, Johnson said laws are needed “to make people do the right thing. That way they have a consequence, if not.” Johnson praised The Model Alliance and founder Sara Ziff for its support of the Fashion Workers Act, which requires financial transparency and accountability in the modeling industry. “Listen, agent, who I love, Iconic Focus, or whatever other agencies I’ve been with, there’s no transparency. I don’t know how much they are getting. I have to rely on them, which I do. I would like to think that everyone is honest. But transparency would be nice. It is like we are children and I am far from a child model. I can take it,” she said.

Johnson credited her father for teaching her to use her voice, “when she had leverage.”

After babysitting the children one day, Johnson recalled “fighting this guy off” after a man pushed her down on a bed and got on top of her. Nearly a decade later, Johnson said she confronted him, and “looked him dead in the eye and said straight to his face, ‘Have you molested little girls lately?'” she said. “That felt good. He just got red and left. Facing it gave me so much strength.”

Johnson said on Monday that the incident occurred at the age of 12 when she drank alcohol for the first time and “later threw up at school”.

Johnson said sexual abuse is a “global dynamic,” and recalled an experience with Cosby, alleging that he gave her the cup of coffee he gave her. “Both times is a miracle [referring also to the babysitting altercation] I got out of there without being raped. Who knows if you would be talking to me on the phone right now, if I had been raped. It closes women’s lives — the trauma,” Johnson said, adding that she now deals with her personal trauma by giving back.

The advocate and model sits on the board of directors of the Barbara Sinatra Children’s Center Foundation, where children who have been sexually abused and children who are sexually abused are given immediate support.

Looking ahead five years, Johnson is wary of speculating on how the fashion industry might change. “I’m not expecting anything. The only thing I can do is – talking to you about it or to a model, who had a bad experience and left because she is traumatized. We’re talking about young women, but not just young young models,” Johnson said. “There are hairdressers and men. The modeling industry is the Wild, Wild West in that waiters and auto workers have unions. There are unions for industries. We are a trillion [dollar] industries, but there are no rules.”

Johnson’s talk is nothing new. She described approaching a heavy-smoking executive about representing her in the 1970s. “He said, ‘What do you have to talk to the press about? You are a model. If you’re not going to pour red wine on Jacqueline Kennedy’s white pants to try to get some press, what’s there to talk about?’”

Despite the fact that the executive was so resistant that he told Johnson he didn’t want to take money from her, she insisted and paid him about $600 a month. Two months later she landed on the cover of Vogue, and the press swung into action, preparing her for media interviews. Sometimes they put in “to explain what she meant.” “I was a bit of a firecracker even then,” Johnson recalled with a laugh.

The best of WWD