Christopher Howse is traveling the nation to talk to local people about his high street. How it has changed and what they miss… This week, Christopher explores Marlborough in Wiltshire.

“This is a famous man,” said an old man in a panama hat who was talking to a friend – a retired colonel from the RAMC – on the sunny side of Armarlbride Street.

He meant me, because there is a good overlap between them The Telegraph and Marlborough. And there is another overlap with Waitrose, and more on that – key to the success of the High Street here. I wish I had a hat, too, to take in response to the welcome extended before me.

“The King, when he was Prince of Wales,” said the man, “visited Marlborough and said: ‘Towns don’t come much better than this’.” It is true that he said so, in those words alone, in 2004, and perhaps the judgment was also true.

The very wide High Street was rebuilt after a great fire in 1653, and it looks very beautiful. It follows a chalk band for three furlongs along the slope above the river Kennet. Marlborough College is on the site of the old castle to the west.

A distinctive feature of the High Street known as pentices. A sort of tiled veranda roof juts out above the shop windows and doors. They are supported by columns, usually in the usual Doric style, forming a modest colonnade along the street, as at the Pantiles in Tunbridge Wells. Winchester also has a series of ancient houses known as the Pentice.

In Marlborough the pennies can provide enough shelter for small tables of coffee drinkers, or for couples looking in shop windows. Pennies stands in front of the Merchants House through a 17th century belfry, the showpiece of the town. Pevsner’s guide to Wiltshire describes it as “exuberantly native”. Oddly enough, one of the few empty shops on the street is the old Clarks shoe store on the ground floor, now To Let.

Right next to the Town Hall, there is a pair of glorious buildings, a clothes shop and a coffee shop, not only with pentices with columns, but, on the first floor, a row of Venetian windows.

These windows are not quite as Sebastiano Serlio, the Renaissance architect, imagined them. They have the same round-headed window in the center and a pair of square-headed windows on either side. But here, the glazing bars of the middle window cross in the upper part to make a nice Gothic pattern. There are four of these Venetian windows in a row, the outer pair wrapped around a projecting bay. The effect is inventive and satisfying.

I’m sure such beauty makes for a happier home. More practically, the width of the street, which has traditionally allowed a large market to take place, allows parking on both sides and down the middle. People can come and park for a few minutes while dropping into a store.

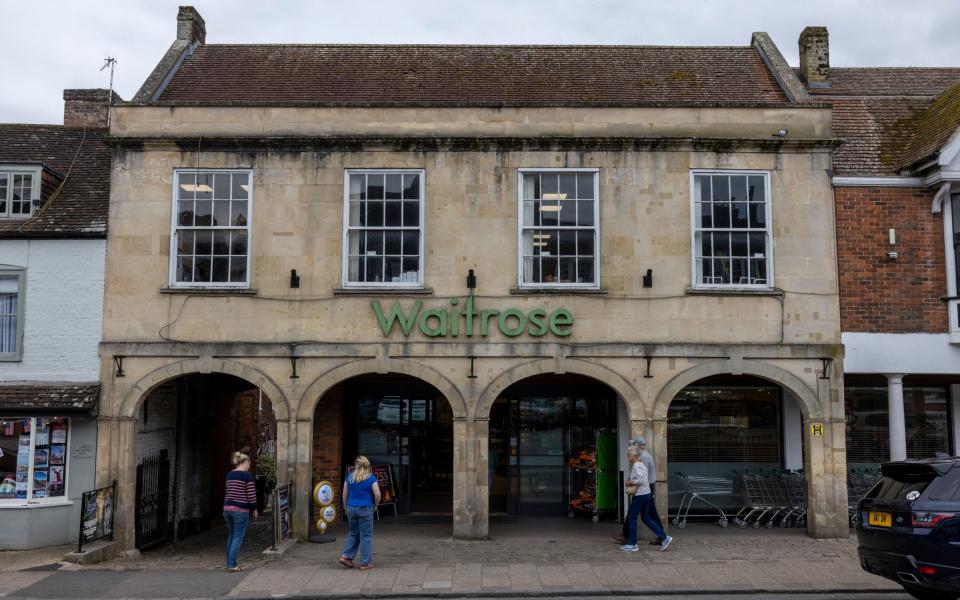

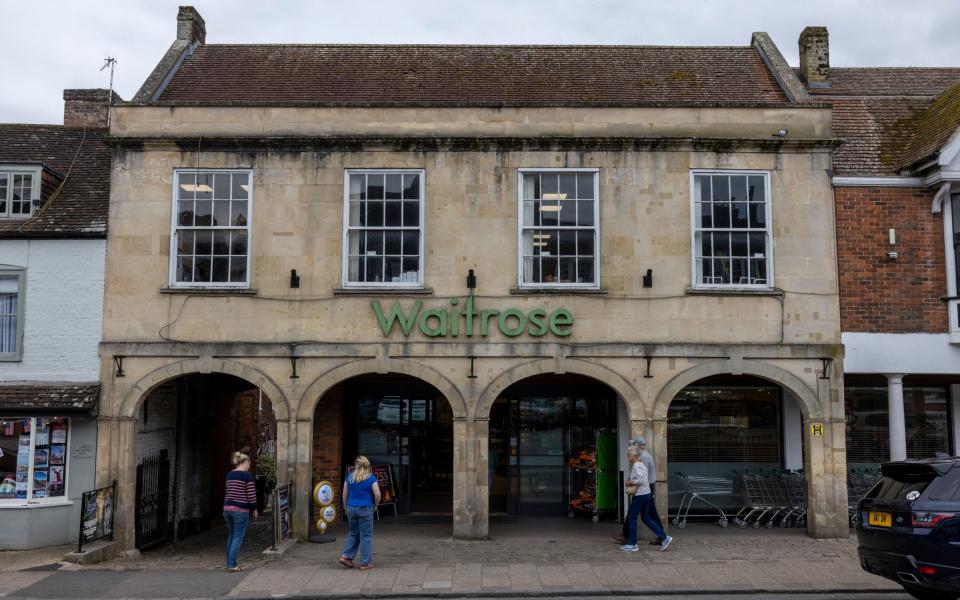

There is also parking around the back of Waitrose. The supermarket’s presence is not immediately obvious in the row of buildings on the south side of the street, as its entrance is in a Georgian-looking stone-fronted building. In fact, it was built in old-fashioned style in 1859 as the Corn Exchange by local bigwig Mark Ailesbury.

Demand for the corn exchange declined and in 1915 it became a cinema, the Electric Picture Hall. The cinema closed in 1974. (Today, the Parade Cinema thrives in a beautiful brick-fronted building off the High Street, and, as well as new film releases, shows reruns from the National Theatre, the Royal Opera House and the Royal Ballet .)

Then Waitrose was able to build its supermarket inconspicuously, and provide parking at the back, thanks to a decision taken almost 1,000 years ago. Property along the High Street was held by a Norman system known as burgess tenure. The parcels of land behind the houses were long and thin. This has allowed infill over the last few decades, with some housing and the famous Waitrose.

If shoppers come into town to use the supermarket, they also use other shops. Tesco, on the other side of the river, gives the High Street a smaller advantage from the number of fishermen. Emma, the young woman behind the bar in the Green Dragon, goes to Waitrose for her weekly shop, saying it’s cheaper than Tesco because of the quality.

The High Street consists of some pleasant old buildings in the local style. The most common facade is suspended tiles, often with scalloped tiles. There are some brick facades, again in the local style, with headers (the narrow end of the brick) of burnt ash gray and the spandrels and dressings around the windows in light red.

In fact, many ancient building facades include timber framing. They were not all burnt down in 1653. Behind the tiled gable of the White Horse Bookshop is a Tudor-era timber building.

I went into the White Horse to buy some postcards. “Yes, we accept cash,” said the lady at the till with a smile. “But we have a problem. Lloyds Bank is closing. It is the last bank in Marlborough, now that HSBC and Barclays have gone. I don’t know what we will do then. Use the Post Office, perhaps. But without anyone going to the bank, fewer feet pass our door.”

My own foot led me past the Norman church of St. Mary at the east end of High Street, behind the decidedly Edwardian Town Hall of 1902 (which must be in distinguished architectural company).

The church also burned down in 1653, but the shell survived, restored with post-fire elements such as neoclassical columns on the south side of the nave. You can still see the fire-red Norman stonework.

Fires didn’t stop in 1653. Polly Tearooms, where I had a rather rich slice of cake, has no top floor because of one in 1966. Its next-door neighbor was then renovated, in a grim, bulky way, to make money. Pevsner’s disapproval as “the worst disruption to the High Street”.

Outside St Mary’s, London Road is an extension of High Street that runs down to the bridge over the river. Here I found a wonderful old fashioned butcher, Sumbler Bros, in business for over a century. “It’s the oldest continuously trading shop in Marlborough,” Green Aprons owner Steve Frost told me.

He is the kind of butcher who is on first-name terms with the livestock that supplies his joints. Half a dozen butchers were busy behind the long refrigerated display counter with rows of sausages, whole chunks of braising steak, tender chickens, with shop-made pies and cooked hams separated into their own cooling compartments.

I could see if you didn’t like meat, this was not the place to be. But a woman was buying marinated chicken that was vacuum-packed for a weekend barbecue. “The kids love them.”

Next to Sumbler’s is a former pub, now flats, with a curious name: the Five Alls. The large sign hanging over the entrance to the stables showed a Soldier (I fight for all), a Priest (I pray for all), the King (I rule all), a Lawyer (I plead for all) and a Farmer. I pay for everything). Even the iron bar it once stood on is now gone, although the building, like most of the High Street, is listed as an object of special architectural and historical interest.

The stop where I waited for the bus back to Swindon is called Cuirt na Five Uile, as Marlborough station closed in 1961. The traffic was not heavy, although this is a through route. The east-west artery of the M4 is a few miles away.

As the bus went over the potholes on the westbound straight road, I thought about Marlborough’s good fortune to be historic, successful and preserved.

The English hardly understand the antiquity in which they live. At Marlborough College, the Mound was thought to have been the moat of a Norman castle (or, more commonly, Merlin’s grave). Archaeologists date it to 2,400 BC. now, and, after Silbury Hill, it is the largest Neolithic mound in Europe.

Before the recent planning laws, no one cared about the owners of old buildings like Marlborough to preserve them. They formed part of a local culture of following in the footsteps of the fathers and imitating the desired fashionistas. So pennies, tile-hangings and Venetian windows. More of that, and less generic, unrooted, unwanted shopping malls and high-rise apartments would do us all good.